I imagine our readers have never stopped to count how many times a day they hear or say muito obrigado [thank you in Portuguese; literally, much obliged – trans.], even in a world where this expression is becoming rarer. I would also doubt being the first person to make these genial words echo in your ears today.

However, as often happens with things that we do on a daily basis, the use of this formula has become considerably timeworn, and its deeper meaning is now unknown to almost all those who use it on a daily basis. Assueta vilescunt…

Some see “muito obrigado” as a simple member of that family whose matriarch is the noble lady “good manners”, whose siblings are the aristocratic “please” and the genteel “excuse me”, and whose cousins are so many other well-known “magic words” that are learned as a child.

But in reality, behind these two seemingly insignificant words lie valuable lessons about the act of expressing gratitude, which is both common and rare, simple and beautiful.

In each language, a different nuance

English-speaking people usually express their gratitude with “thank you”, and the German formulation is not much different: vielen Dank. The Italians say grazie and the Spanish gracias, both influenced by Latin: gratias ago. The French prefer merci beaucoup; the Arabs, shukran jazeelan; the Japanese, for their part, opt for the affable and austere arigato.

It is true that all these formulations have the same purpose: to thank. However, in each of the languages, the way this is done has its own nuances.

St. Thomas Aquinas explains that the virtue of gratitude has three degrees: “The first is that a man recognizes the benefit he has received; the second consists in appreciation and thanksgiving; the third consists in making retribution in the appropriate place and at the appropriate time, according to one’s means.”1

Of course, it is not necessary to have recourse to all three elements at the same time; it is up to the prudent man to decide according to the circumstances whether one is enough, or whether he needs to put all three into practice.

Perhaps that is why none of the languages mentioned above express all three degrees of gratitude simultaneously. Each, in its own way, refers to one of them.

The first step to gratitude: an exercise of the memory

To recognize. This is what thank you tries to do: in the English language to thank and to think are etymologically the same word. And so it is in German: zu danken – to thank – comes from zu denken – to think. This represents the first degree of gratitude. In fact, you cannot thank a benefactor without considering, recognizing or thinking about the benefit he has rendered you.

This recognition must be present, above all, in our relationship with the Lord. St. Thomas says that in order to perfectly fulfil the Commandment to love God above all things, the first condition is to “keep in mind the divine benefits.”2

We see, then, that if we want to acquire the virtue of gratitude, we have to start by exercising our memory well… This is clear: whoever does not remember their benefactor does not give thanks; and whoever does not give thanks, ponders St. Augustine,3 loses even what they have.

Sometimes it is not enough to acknowledge

The form of gratitude in a large number of Latin languages fits into the second degree listed by St. Thomas: thanksgiving. Examples of this are Latin itself – gratias ago –, Spanish – gracias –, Italian – grazie – and French – merci.4 The Arabic expression shukran jazeelan also refers to thanksgiving.

In most cases, it is not enough to recognize only inwardly the benefit we have received; it is right and even essential to express our gratification to those who have done us good; in fact, it is a duty of politeness. Sometimes, however, we do not even need to do so with words; the simple demonstration of contentment already constitutes gratitude.

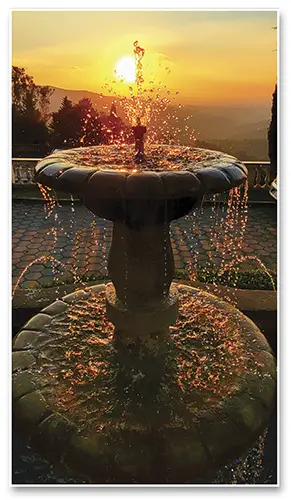

This is especially true in our relationship with God. Dr. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira’s comparison in this regard is singularly beautiful: “The water of a fountain that hits the ground and then splashes upwards in a series of drops is also a symbol of the gratitude of the beneficiary on whom heavenly favours have fallen and who throws his filial and jubilant thanksgiving upwards towards heaven.”5

Fountain – Mairiporã (Brazil)

When, on the contrary, explains St. Bernard,6 we are ungrateful to our Divine Benefactor, He may consider the favour He has done us to be lost and will hardly grant it to us again, so as not to waste the treasures of His Providence.

An obligation spontaneously fulfilled

Finally, we come to our dearly beloved muito obrigado. So what does this expression mean? Do we want to show our benefactor that we do not appreciate his gift and are “obliged” to accept it? Or do we think that, distrusting their good intentions, they have been “obliged” by something or someone to do us a favour? Certainly that is not it…

In fact, this distinctive formula is the only one to be clearly situated on that third and deepest level of gratitude that the Angelic Doctor describes, and which obviously presupposes the two previous ones: ob-ligatus; it is a bond, a duty to reciprocate.7

When we say “obrigado”, we show our benefactor that we are so pleased with the good we have received that we feel an obligation to repay him in some way. However, this obligation is not felt as a kind of debt, but rather as a need that comes from the heart, based on a sense of honour.

In this way, retribution becomes an “obligation that is spontaneously fulfilled.”8

For this very reason, adds St. Thomas,9 it is not fitting that such repayment be immediate, because one who rushes to repay does not have the spirit of a grateful man, but rather of a debtor who cannot wait to be rid of the debt. We should wait for the opportune moment.

We must surpass the good we receive

At least in this respect – perhaps one of the only ones – we can say that Portuguese and Japanese are very similar. The attractive arigato also refers to the third and highest degree of gratitude, but in a peculiar way.

Arigato can mean: life is difficult, it is hard to live, and can also signify rarity or excellence.10 The last two meanings are easy to understand: in a world where the general tendency is for everyone to think of themselves, giving thanks – such a natural and simple act – becomes rare and even excellent. But how can “life is difficult” be related to gratitude?

When it comes to retribution, St. Thomas Aquinas11 – quite rightly – is very demanding. According to him, the reward must be greater than the benefit received.

This is why: since we have been the object of a favour and therefore a gratuitous gift, we have acquired a real obligation to give something freely. Now, if the retribution is less than the benefit, our “debt” of honour will not be “paid”; if it is equal, we will only have repaid what we received. Therefore, in order to reciprocate worthily, it is necessary to surpass the good that has been generously bestowed upon us.

However, if it is sometimes difficult, or even impossible, to even equal in merit the good done to us, how can we surpass it?

For example, we will never be able to give God – or even our parents – all the honour due to Him for everything we have received. This is how we understand how “life is difficult”, how “it is hard to live”, from the moment we have been the object of a benefit and are willing to repay it accordingly.

What is the solution, then? Would it not seem better to never have been the object of a kindness, to run away from any and all benefactors, than to have to bear such a heavy burden as gratitude? If thought like this have come to the reader’s mind, please remain calm; the solution is much easier.

Gratitude is not synonymous with payment

First of all, we need to remember that true benefactors act disinterestedly, without expecting retribution. Therefore, running away from them for fear of becoming an eternal debtor would be like trying to hide from the sun at midnight…

Today’s world, where everything is commercialized, has very little comprehension of the virtue of gratitude. That is why Dr. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira lamented:

“The virtue of gratitude is seen today as a matter of accounting. Accordingly, if someone does me a favour, I should calculate a like response, with a portion of gratitude mathematically equal to the benefit received. It is, then, a type of payment: a favour is paid with friendship, just as merchandize is paid with money. I received a favour, and consequently I must wrench from my soul a sentiment of gratitude.”12

True retribution is much more accessible than we realize, because the benefit is not paid for with gold or silver. The treasure from which gratitude springs is within ourselves: our heart.

The true meaning of this forgotten virtue

To better describe the true face of such a noble virtue, I turn once again to Dr. Plinio, who explains it with the precision, depth and flight of soul proper to him:

“To be grateful is first of all to acknowledge the value of the benefit received. In the second place, it is to recognize that we, in ourselves, do not deserve the benefit. Thirdly, it is the desire to dedicate ourselves to the one who served us in proportion to the service rendered, and particularly to the dedication shown toward us. As St. Therese used to say, ‘Love is repaid by love alone.’ For either a person repays dedication with dedication or they have not paid at all.”13

Mass in the Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Caieiras (Brazil)

A contest between dedications: this is the virtue of gratitude. How beautiful and noble it would be to rival one another when it comes to affection, kindness and dedication. According to St. Paul, this is the only debt worthy of a Christian: “Owe no one anything, except to love one another” (Rom 13:8).

Now, what does this dedication consist of, if not that bond so well expressed in muito obrigado – ob-ligatus? What depth in such simple words! Pronouncing them is very easy, but putting them into practice is another matter.

In this sense, we can say with Msgr. João Scognamiglio Clá Dias: “How rare is the virtue of gratitude! Frequently it is practised in word only, out of politeness. Yet, to be authentic, it must flow sincerely from the heart.”14

Finally, aware of how much effort the reader has made to reach the end of this article, I would not dare to close it in any other way than with a sincere and warm muito obrigado! ◊

Notes

1 ST. THOMAS AQUINAS. Summa Theologiæ. II-II, q.107, a.2.

2 ST. THOMAS AQUINAS. De decem præceptis, a.1.

3 Cf. ST. AUGUSTINE OF HIPPO. Sermo 283, n.2. In: Obras Completas. Madrid: BAC, 1984, v.XXV, p.96.

4 “Merci is derived from merces – salary – which in popular Latin took on the meaning of price, from which were derived those of favour and grace” (LAUAND, Jean. “Obrigado”, “Perdoe-me”: a Filosofia de São Tomás de Aquino subjacente à nossa linguagem do dia a dia. In: Hospitalidade. São Paulo. Year XVI. N.2 [May-Aug., 2019], p.142, Note 11).

5 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Como grandes voos de espírito [Like Great Flights of Spirit]. In: Dr. Plinio. São Paulo. Year IV. N.43 (Oct., 2001), p.34.

6 Cf. BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX. Sermo 27, n.8. In: Obras Completas. Madrid: BAC, 1988, v.VI, p.232.

7 Cf. LAUAND, op. cit., p.142.

8 ST. THOMAS AQUINAS. Summa Theologiæ. II-II, q.106, a.1, ad 2.

9 Cf. Idem, a.4.

10 Cf. LAUAND, op. cit., p.142.

11 Cf. ST. THOMAS AQUINAS, Summa Theologiæ. op. cit., q.106, a.6.

12 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Talk. São Paulo, 1/6/1974.

13 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Talk. São Paulo, 27/12/1974.

14 CLÁ DIAS, EP, João Scognamiglio. Ten Cures and a Miracle. In: New Insights on the Gospels. Città del Vaticano: LEV, 2012, v.VI, p.412.