The heroic demonstrations of faith that are given in Africa demand our respect and inspire our veneration. If naivety had led us to imagine that the age of martyrs was relegated to history books, and to forget that we will have tribulations in this world (cf. Jn 16:33), our African brothers and sisters today bring us copious testimonies of blood, putting to shame, by their example, so many parts of the world afflicted by a veritable demographic winter with regard to Baptisms. There, where religious persecution is rampant, the number of children of God and ministers of Our Lord Jesus Christ is increasing.

In honour of these our brethren, we evoke the example, not of martyrdom, but of Christian life and heroic virtues of the Venerable Pierre Toussaint.

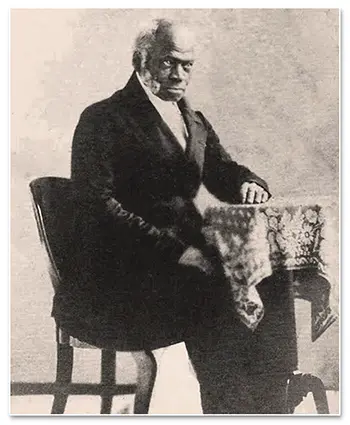

Even at first glance, the characteristics of a true gentleman and, moreover, of a humble Catholic man, a master of his passions, can be recognized in his posture, his penetrating gaze, the welcoming and discreet inclination of the head, his hand resting calmly but firmly on the table, in short, in the overall impression he gives of nobility, cleanliness, strength and modesty. What is the origin of so many qualities?

Pierre was born into slavery in 1766 in Haiti, then a French colony on the western part of the island of Saint-Domingue. The masters he served, the Bérard family, were affluent landowners. Let us not imagine, however, the cruel slavery of the pagans, nor certain abuses of the colonial period. His grandmother Zenobia, was the children’s nanny, and became so esteemed for her loyal service that she was granted her freedom. His mother, Ursula, was Madame Bérard’s private maid. Pierre, in turn, devoted himself to agriculture and won everyone’s hearts with his joy and gentility. An acquaintance describes him: “I remember Toussaint among the slaves, dressed in a red jacket, full of spirits and very fond of dancing and music, and always devoted to his mistress” 1, the young and cheerful Mrs. Bérard.

When Jean Bérard returned to France with his family and some slaves, leaving his eldest son in charge of his lands in America, the French Revolution broke out, which soon spread throughout the colonies with the frenetic furore of the dubious ideals of fratricidal “liberty”. Realizing that his properties in Haiti were at risk, the patriarch decided to flee to New York, hoping to recover them when peace returned.

To this end, he travelled a few years later to the island of Saint-Domingue, while his wife remained in New York awaiting news. And news soon arrived, as tragic as the dramatic succession of Job’s misfortunes (cf. Job 1:13-19). A first letter from Mr. Bérard announced that all the properties in the colony were irretrievably lost. Soon a second letter informed Mrs. Bérard of her husband’s death from pleurisy. She had barely recovered from the trauma when notice of the bankruptcy of the firm where the family’s assets were invested arrived at her doorstep. All that remained of the poor unfortunate woman’s riches was a devoted and generous slave, the good Pierre, who from that moment on devoted himself entirely and selflessly to his mistress.

It was not long before angry creditors came knocking. Having forsaken the luxuries she once enjoyed, Madame Bérard found herself in an increasingly distressing situation. She summoned Pierre one day, gave him some jewellery and told him to sell it for the best price possible. With a heavy heart, he could not bring himself to obey. A few days later, gathering all the savings he had made from his work as a hairdresser, he surprised his mistress by placing two packages in her hands: one with the jewellery and the other with the equivalent amount of money. To the hairdresser who came to collect old debts, he offered a period of service in exchange and paid off the debt, completing the amount with the New Year’s bonus he had received.

“His industry was unceasing, every hour of the day was employed; when released, his first thought was his mistress, to hasten home and try to cheer her. […] His great object was to serve her”2 and he did so with to the utmost, sacrificing himself silently. Whenever he could, he set her table with delicacies and rare tropical fruits. Seeing her downcast, he would persuade her to prepare a party. Pierre would invite a few close friends and, on the appointed day, would style his mistress’ hair, crowning the finished product with some exotic flower that he had secretly bought. He would set the table, decorate the house, and welcome the visitors at the door, dressed in grand style.

There was one thing he could not bear: “I knew her,” he would say, full of life and gayety, richly dressed, and entering into amusements with animation; now the scene was so changed, and it was so sad to me !”3 Pierre’s principal biographer wisely reflects: “There was something far beyond the devotion of an affectionate slave; it seemed to partake of a knowledge of the human mind, an intuitive perception of the wants of the soul, which arose from his own finely organized nature.” Until the end of his life, he would be his mistress’ aide at all times.

With his sweet, helpful and religious soul, he walked the streets of New York, sought after by high society ladies for his hairdressing services. Curiously, it was not uncommon for coiffure to be relegated to second place, as Pierre found himself obliged to devote himself to caring for souls, as he had acquired a reputation as an admirable counsellor. Maria Anna Schuyler, daughter-in-law of General Philip Schuyler, considered Pierre her only confidant and called him “my saint.” Many souls benefited from his generous work, his wise words, or his simple presence.

After Mrs. Bérard’s death, Pierre’s small apartment-office became a shelter for orphans, refugee priests, and workers who had fallen into poverty, for whom he interceded with important people in the city, finding them employment and helping them to organize their lives. He lived to the age of eighty-seven, as a Catholic and persevering recipient of the Sacraments, in an environment that was hostile to the Faith.

Untainted by envy and ignorant of the bitterness of rebellion, Pierre Toussaint displayed, as a lesson for history, the hallmark of a true Catholic: generosity filled with joy. Service ennobled him, and admiration – an act of justice that we joyfully render to all that is superior to us – endowed his soul with delicacy, insight, and good taste. He understood that God loves all men and therefore arranged them in a harmonious scale of perfections, so that each may proceed according to the gift he has received (cf. 1 Pt 4:10-11) and all may be enriched by becoming slaves to one another through charity (cf. Gal 5:13). ◊

Notes

1 LEE, Hannah Farnham Sawyer. Memoir of Pierre Toussaint, Born a Slave in St. Domingo. 3.ed. Boston: Crosby, Nichols and Company, 1854, p.15.

2 Idem, p.20.

3 Idem, p.25.