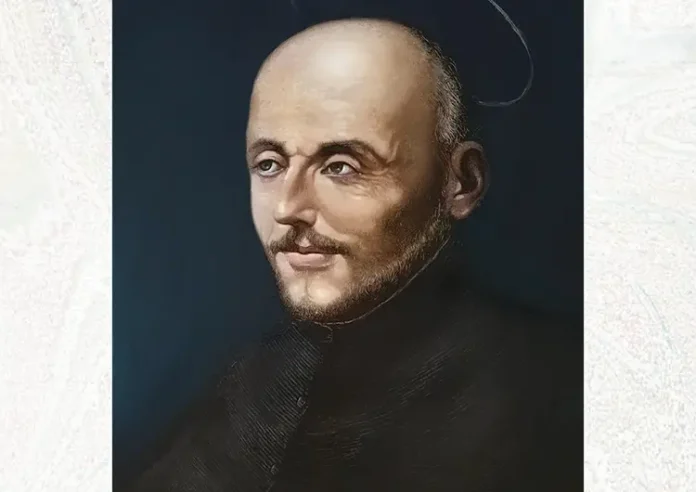

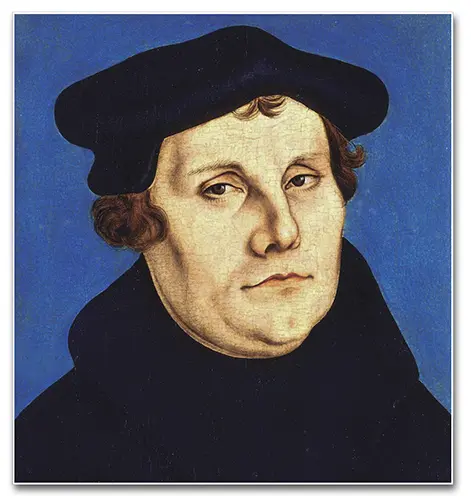

Portrayed by their contemporaries, the facial features of the two men illustrated on these pages – who, without ever having met one another, were perhaps the greatest antagonists in the 16th century – are impressive for their eloquence.

* * *

St. Ignatius of Loyola, in the prime of his intellectual maturity, immediately suggests an early decline in physical vigour: he is thin, with noticeable balding and facial creases. A man much more accustomed to exercising his moral rather than his physical qualities, of these last, the former soldier no longer reveals anything… except perhaps his gaze.

The Saint appears to be in conversation with someone. His eyes, though large, are half-closed and the orbicular muscles are contracted, a sign of acute, penetrating and dispassionate observation. In fact, this must be a frequent activity for him, judging by the pronounced expression lines.

His attention seems to be focused much more on the soul of the person speaking than on the commentary being made, and his gaze seems to say: “I penetrate you, but I am impenetrable.”

In contrast, his mouth – rather small, as if to only allow the passage of words that truly deserve to be spoken – with its firm, well-defined contours, is closed in a friendly and understanding smile. The neck inclines almost imperceptibly towards his supposed interlocutor, as if assuring him: “I welcome you and am willing to help you, regardless of the faults I discern in you.”

The whole therefore gives the impression of authentic kindness, focused on others, but reserved, firm, austere, formal.

* * *

Luther is quite the opposite. Still full of vigour, his abundance of adipose tissue is lavishly distributed on all sides, further reinforcing the rounded obliqueness of his features.

His nose is large and fleshy. His mouth, which, being the uppermost end of the digestive tract, constitutes a kind of “embassy” of instinct in the head – the most “rational” region of the body – is wide and sinuous in outline, sitting spaciously on a powerful chin.

The bone structure is pronounced. Everything suggests robustness, voracity and vehement desire, veiled by an ostensibly relaxed but not appeased physiognomy.

In fact, the hint of a smile and sparse hair contribute to forming an imponderable irony in a state of gestation, ready to erupt into loud and sonorous, albeit somewhat unbalanced, laughter.

This man, of undeniable intellectual ability, immediately betrays himself as a lover of lavish dining, of easy pleasure and of jocular conversation… At first glance, he is precisely the kind of figure that many might be tempted to consider likeable.

* * *

We would not hesitate to say that many of our contemporaries, unaware of the identities of these two characters, if asked to invite one of them to a relaxed weekend meal, would choose Luther.

After all, does the lean thinker not seem too serious and analytical to make for easy-going company? On the other hand, who would deny the portly and good-humoured man a place at the table?

However, perhaps this choice would not be the most accurate one.

While a first physical analysis points to the German reformer’s vital force, a second indicates the service to which it is devoted. Is there not a hint of sadness in his look? While St. Ignatius is entirely focused on a goal, on his neighbour, on God, Luther turns inward, towards himself, towards the constant torments of conscience that assail him.

A proud, irascible man, the latter would hurl insults with the same ease with which he would tell a joke. His volatile temperament does not imply security. He is indeed a man ahead of his time, in the sense that he fits perfectly into ours.

The founder of the Society of Jesus, for his part, while retaining all the austerity of the recollected man, of the Jesuit and – why not say it – of the good Spaniard, although he somehow inhabits the isolation of an inaccessible interior light, deserved to receive, from countless among the most notable of his time, the title of father.

Someone might object that judgements based on facial expressions, essentially on appearances, tend to be superficial and therefore fallible. We agree. That is why we must try to reconcile our impressions with what history tells us about both of these figures.

But, incidentally, is this not exactly the kind of hasty judgement we make when we admire, for example, one of the so-called influencers, whose private life and works we know nothing about?

“Cursed is the man who trusts in man” (Jer 17:5), says Scripture. How many people deceive themselves, thinking they have found a friend, when they have found nothing more than a good appetite and a good laugh! What is the value of an illusory affinity without authentic and solid friendship?

It is in difficult situations that we discover who our true companions are: “Amicus certus in re incerta cernitur.”

At times like these, that circumspect gentleman could prove to be a lifeline, while the hearty conversationalist might become a weight that would drag us into the abyss.

May this serve to teach us to discern and to be true friends. ◊