In his characteristic style, St. Luke offers us a detailed description of the event that marked the beginnings of the Church: Pentecost. After tongues of fire rested upon each of the Apostles, “they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance” (Acts 2:4). This marvellous phenomenon, which surpasses the ordinary capacities of human intelligence, called glossolalia by theologians, is listed by St. Thomas Aquinas1 among the graces that are gratis datæ or gratuitous, that is, graces freely granted to someone, not for their own personal advantage, but for the benefit of others.

It was clearly an exceptional event, since learning a new language normally requires a certain level of effort and dedication, varying in intensity depending on the individual’s abilities and aptitudes. Only the Spirit of Intelligence could perform such a miracle…

Something different, however, happened when the sacred authors, under the inspiration of the same Holy Spirit, committed the Word of God to writing. According to the designs of Divine Providence, the Scriptures were not to be a complex “symphony of languages,” like that of the day of Pentecost. When inspiring the men who composed the Sacred Books, the Paraclete chose to use the languages specific to each of them, and therefore, only three languages appear in the original manuscripts of the Bible.

The first language of the sacred texts

Composed between the 13th century BC and the 1st century AD, the Scriptures narrate, in their historical context, events that unfolded in the Eastern Mediterranean, North Africa, and the Middle East. Struggles, victories, and defeats, sorrows and joys, miracles and trials… The Israelites experienced great moments during the fourteen centuries during which the Holy Books were written! Considerable changes also contributed to altering the customs of the Chosen People during this long period.

“The prophets Jerimiah and Baruch”, by Rutilio di Lorenzo Manetti – National Gallery of Ancient Art, Rome

There is no doubt that Hebrew was the first language used by the children of Abraham when composing the Holy Scriptures. Although we know little about the original texts, the writings in this language constitute almost the entire Old Testament.

We know that a rich variety of Hebrew versions of the Bible circulated among the Jews. Indeed, in the first century AD, Judaism was quite divided among itself, with four main factions: Pharisees, Sadducees, Zealots, and Essenes, each with its own version of the Holy Books. With the invasion of Jerusalem in 70 AD and the subsequent Roman wars, this multiplicity of sects, and consequently, biblical texts, ceased. With the destruction of the Temple, the Sadducees’ role was extinguished; the Essenes disappeared when Titus’ troops ruined their properties at Qumran; finally, in 135 AD, when Rome managed to suppress the Zealot revolt, the latter disintegrated. The only group left was the Pharisees, to whom is associated the biblical version that endured and established itself as the only one in Judaism: the pre-Masoretic text.2

Like any other Hebrew writing, it contained only consonants, since vowels were transmitted orally. Over time, this characteristic of the Hebrew language became a source of doubts regarding certain words whose consonants could be pronounced in different ways, giving rise to diverse meanings. To deal with this concern, from the 7th century onward, Jews called Masoretes – a name derived from the word massora, meaning tradition – established the vocalization of the text.

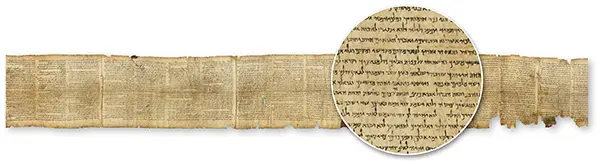

For a long time – until the last century, in fact – it was believed that the pre-Masoretic text, compiled in the 2nd century,3 was the oldest. But a completely fortuitous event would disprove this hypothesis.

In early 1947, a Bedouin shepherd was passing through the region called Khirbet-Qumran, near the Dead Sea. While practising his aim by throwing stones into the numerous cavities in the mountains, he heard the characteristic sound of pottery shattering. He hurried to the site, where he soon discovered what had happened: one of the stones had hit a vessel containing valuable biblical papyri and parchments, and there were nine other amphorae in the cave… Later studies confirmed that the writings belonged to the Essene community and could be dated between the 3rd century BC and 1st century AD.4

The new language of Judah: Aramaic

Since the 13th century BC, Hebrew remained the only language used to convey the Word of God in sacred manuscripts. Over time, however, another language was also used by hagiographers: Aramaic, which we find in short passages from the Books of Daniel, Ezra, and Jeremiah. What determined this change?

Aramaic was the official language of the Assyrian Empire, as well as of its two successors: the Babylonian and Persian. During the reign of Ahaz in the 8th century BC, the Kingdom of Judah became a vassal of Assyria as a result of the Syro-Ephraimite War,5 and it disappeared in 600 BC with the fall of this empire to Babylonian military might. In 587 BC, Nebuchadnezzar II’s army captured Jerusalem, and a large portion of the Jews were deported to Babylon. This began the period of exile, during which they would spend no less than fifty years outside their homeland.6

It was only in 539 BC that Cyrus, king of Persia, having conquered Babylon and subdued all the peoples under its control, would allow the Jews to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the Temple.

It was in connection with these events that the Aramaic language entered Jewish popular culture, replacing the Hebrew, and so it would remain for many centuries, to the point of being the vernacular language in the time of Our Lord Jesus Christ.7

The Book of Isaiah in one of the Hebrew manuscripts found near the Dead Sea – Israel Museum, Jerusalem

With Alexander the Great, a new era

The years passed, and the great Persian Empire declined, giving way to another power emerging on the horizon.

The Scriptures recount that, “After Alexander son of Philip, the Macedonian, who came from the land of Kittim, had defeated Darius, king of the Persians and the Medes, he succeeded him as king. (He had previously become king of Greece.) He fought many battles, conquered strongholds, and put to death the kings of the earth. He advanced to the ends of the earth, and plundered many nations. When the earth became quiet before him, he was exalted, and his heart was lifted up. He gathered a very strong army and ruled over countries, nations, and princes, and they became tributary to him” (1 Mc 1:1-4).

In the 4th century BC, Alexander the Great, at only thirty years of age, expanded his vast empire throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Gradually, his new lands changed their semblance, taking on the characteristic features of Hellenism. Among the Israelites, there were once again instances of apostasy and religious infidelity.

According to the First Book of Maccabees, “In those days lawless men came forth from Israel, and misled many, saying, ‘Let us go and make a covenant with the Gentiles round about us, for since we separated from them many evils have come upon us.’ This proposal pleased them, and some of the people eagerly went to the king. He authorized them to observe the ordinances of the Gentiles” (1:11-13).

After Alexander’s unexpected death in 322 BC, the gigantic empire was fragmented among his generals. The Jews, who until then had enjoyed a certain peace, were subjected to the rule of the Ptolemies, who soon dealt them a terrible blow: in 312 BC they took over the city of Jerusalem, which saw part of its inhabitants deported to Alexandria, in Egypt.8

This city would be the site of an event of outstanding importance in the history of the Bible.

Greek in the Scriptures

According to an ancient tradition – more symbolic than strictly historical – the Egyptian King Ptolemy II, intending to gather all the writings of the ancient world into his library, sent a group of representatives to Jerusalem to obtain a copy of the Scriptures, as well as scholars capable of translating them into Greek. For this purpose, seventy-two wise men were chosen, who, on an island near Alexandria, completed their own work in seventy-two days.

By a marvellous miracle, each one’s translation coincided word for word with the others’ texts, a clear sign of divine intervention and inspiration. The work would become known as the Septuagint Version. It is worth noting that most of the Old Testament quotations used in the New Testament come from this version.

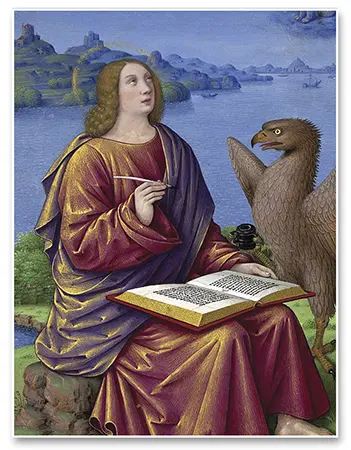

In the biblical canon, there are also texts written directly in Greek, such as the Book of Wisdom, the two Books of Maccabees, and some parts of the Books of Esther and Daniel. Furthermore, the entire New Testament – with the exception, according to ancient authors, of the Gospel of Matthew, written in Aramaic, and the Epistle to the Hebrews, composed by St. Paul in Hebrew and translated by St. Luke into Greek – was written in this language.9

St. John the Evangelist, “The Grandes Heures of Anne of Brittany” – National Library of France, Paris

The Hellenistic era was succeeded by the Roman era: the Caesars’ rule reached enormous proportions, encompassing the entire Mediterranean region. The Greek language, however, remained deeply rooted in much of the empire.

This factor was decisive for the expansion of Christianity. Having received from Our Lord the mandate to go into the whole world and preach the Gospel to every creature (cf. Mk 16:15), the Apostles and disciples had at their disposal a language considered universal and a translation of the Old Testament in that language, the Septuagint Version, which the Church would later adopt as its own.10

In the end, which is the language of the Holy Spirit?

Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek. Which of the three languages proved most appropriate for transmitting Revelation? The truth is that, regardless of their respective languages, the hagiographers became authentic repositories of the “living and active” Word (Heb 4:12).

If we consider the history of sacred philology from a higher perspective, we will see that Hebrew has the inestimable value of being the language in which eminent prophets prophesied tragic and grandiose events, especially the coming of the Messiah; Aramaic, the immense glory of being the language of Our Lord Jesus Christ; Greek, the singular merit of having been used to compose the Holy Gospels…

The three languages together are, in short, of incomparable greatness because, at a given moment, they served as instruments of the Divine Paraclete who manifests Himself to whomever He wishes, at the time and in the language He wishes. ◊

Notes

1 Cf. ST. THOMAS AQUINAS. Summa Theologiӕ. I-II, q.111, a.4.

2 Cf. CARBAJOSA, Ignacio; ECHEGARAY, Joaquín González; VARO, Francisco. La Biblia en su entorno. Estella: Verbo Divino, 2020, p.450-451.

3 Cf. Idem, p.450.

4 Cf. Idem, p.468; 471.

5 Samaria and Damascus joined forces to attack the Kingdom of Judah, as the latter refused to join them in combating the Assyrian power. Faced with this threat, Ahaz sought help from Tiglath-Pilesar III, king of Assyria.

6 Cf. CASCIARO, José Maria (Dir.). Introducción. In: Sagrada Biblia. Antiguo Testamento. Libros Históricos. 2.ed. Pamplona: EUNSA, 2005, p.17-18.

7 Cf. CARBAJOSA, op. cit., p.426.

8 Cf. SANTOS, Moisés Alves dos. Introdução aos Livros dos Macabeus. In: Bíblia Sagrada. Edição de estudos. 9.ed. São Paulo: Ave-Maria, 2018, p.679.

9 Cf. MÁLEK, Ludvik et al. El mundo del Antiguo Testamento. Estella: Verbo Divino, 2021, p.379-380.

10 Cf. SECOND VATICAN COUNCIL. Dei Verbum, n.22.