Hermit, apostle, founder, mystic, prophet, exorcist… These diverse facets harmonized in the soul of this Carmelite who, in his excelling love for the Church, became mystically united to her.

Archipelago of the Balearic Islands, Spain. At the south-eastern tip of Ibiza Island, facing the cliffs dropping almost vertically into the Mediterranean, an imposing rocky islet juts up out of the water. Though not far from the coast, the roughness of the sea and the steep shoreline make it difficult to access. Only on clear days do ferrymen dare to make the crossing.

After landing on the craggy coast, a few hours of arduous ascent are needed to reach the top of the island, located at nearly 400 metres above sea level. Just below the peak, carved into the steep rock face is a small cave burrowed into the heart of the deserted mountain.

It is a refuge for birds of prey? Or a shelter for some solitary wild animal? No. However, there are signs in this grotto of the presence of an aquiline soul, a courageous apostle, who withdrew there to pray.

It was on the little island of Es Vedrà that this remarkable hermit discovered the central point of his mission: to serve and defend the object of his ardent love, the Holy Church, which he contemplated mystically under the figure of a maiden.

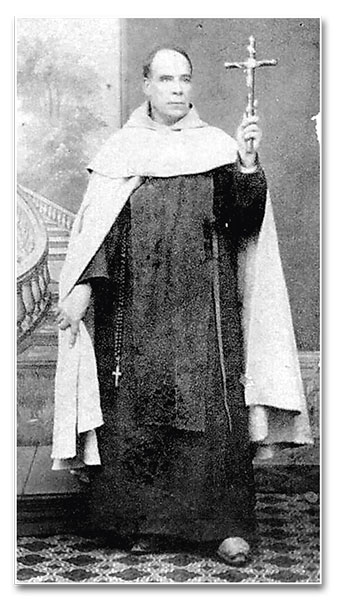

Let us briefly consider the life of this man, Blessed Francisco Palau y Quer.

The burgeoning of a vocation under Elijah’s mantle

He was born on December 29, 1811, in the village of Aitona, into a devout farming family. His penchant for learning gained him entrance into the Seminary of Lérida at the age of seventeen, where contact with the Carmelite priests who provided spiritual assistance to the students opened his soul to the religious vocation.

Undecided as to which order he should enter, he resolved to make a novena to the prophet Elijah, to whom he had been devoted since childhood. On the last day of the novena, the statue before which he was praying came to life and covered him with its mantle. Such a clear sign left no room for doubt: he would be a Carmelite!

He entered the novitiate of Barcelona in 1832. The time was not a favourable one for entering religious life, as the first flares of the liberal revolution had already ignited. Nevertheless, he professed his perpetual vows with impressive resolution and clear-sightedness on November 15, 1833: “When I made my religious profession, the revolution already held in its hand a burning torch to set all the religious houses ablaze and a dreadful dagger to murder the individuals sheltered in them. I was well aware of the pressing danger I faced.”1

His prognostications were soon confirmed. Two years later, when he was a deacon, the Monastery of St. Joseph in Barcelona was burned and all the religious imprisoned. They were soon released, but prohibited by the civil authority from leading a community life. Friar Francisco Palau would remain outside the cloister until the end of his life, maintaining his fidelity to the Carmelite vocation in the manner of St. Elijah: alternating between precious moments of profound solitude and intense action.

The solitary and the apostolic life

After leaving prison, he returned to his birthplace, settling in a grotto on the outskirts of the city. From then on, wherever he went, he built small hermitages or used those provided by nature as his dwelling. He liked to live “in the most deserted, wild and solitary places, for thus with fewer distractions he could contemplate the plans of God for society and the Church.” 2

Defying the government prohibition and following the counsel of his superior, he was ordained a priest in 1836 by the Bishop Jaime Fort y Puig of Barbastro. It was now possible for the young priest to dedicate himself to fruitful action through popular missions and by attending those who sought him, impelled by the reputation for sanctity he had already earned by this time.

However, the integrity of his conduct and the effectiveness of his preaching displeased many… Persecutions and misunderstandings soon arose, coming from both civil and ecclesiastical authorities, and even from his fellow countrymen.

On one occasion, as he prayed in his hermitage after a blessed day of mission, four men who had attended his preaching came up to him. One of them took the lead and entered the grotto with the intention of killing him. Why? For the same motive that the sacred author indicates in the false reasoning of the wicked: “Let us lie in wait for the righteous man, because he is inconvenient to us” (Wis 2:12).

Calmly, the religious asked him:

— Have you come to kill me, brother? It would be better for you to confess, for it has been years since you last did so, and you do not know when God will call you to judgement. Come, repeat with me: I a sinner…

These words moved that hardened soul. Amid sobs, the potential killer confessed his faults, and was soon followed by his companions. His criminal audacity had been vanquished by the meek intransigence of the defenceless anchorite.

Es Vedrà: the solitude his heart desired

In 1840, the Spanish political situation had worsened, obliging Fr. Palau to take refuge in France. For almost eleven years he resided in the Dioceses of Perpignan and Montauban, always living in secluded grottos. A group of disciples gathered around him, giving rise to a nucleus of hermits, as well as to an incipient feminine community. These were the first seeds of his future foundation.

Returning to Spain in 1851, he went to the Diocese of Barcelona, where he was warmly welcomed by Bishop José Domingo Costa y Borrás. A period of intense apostolic activity began, marked by concern for the lack of religious instruction among the faithful and the consequent corruption of customs.

He founded the School of Virtue in St. Augustine’s Parish, a permanent catechesis for adults who sought to confront “error with truth, darkness with light, shadows with reality, falsity with authenticity” and to be “a School that would define and call formal virtue by the names, words and terms proper to it, and to describe the vices by their disastrous and devastating properties.” 3

This was one of his undertakings that bore the greatest influence on society. With time, about two thousand people from all classes, especially workers, were gathering on Sundays to hear his teachings.

The resounding success of the School of Virtue, however, made it the target of malicious calumnies. Based on the false accusation of involvement in the workers’ strikes that erupted in Barcelona, the civil governor closed it in 1854 and exiled Blessed Palau to the Island of Ibiza, where, paradoxically, he found his preferred site for solitude: the little island of Es Vedrà.

“In the Balearic Islands, Providence had prepared for me the solitude such as my heart desired,” 4 he himself narrates. To that rugged rock “nobody can approach except by boat; and its sheer cliffs rise so abruptly from the water that they can only be scaled by native experts. This is where I withdraw, from time to time, for my solitary life.” 5

The graces received there were such that, after six years of exile in the Balearic Islands, he often returned to Es Vedrà to “render accounts to God for my life and to consult the designs of His Providence,” 6 he writes.

Mystical union with the Church

The year 1860 held a crucial event for him, one which would give meaning to his life. According to his own commentary, the time of his youth, his entrance into Carmel and the vicissitudes that followed, the periods of isolation, his priestly ministry and the resulting tribulations all amounted to a prolonged search: “I had spent my life in search of object of my love, until the year of 1860. I knew well that it existed, but how far I was from imagining what it was!” 7

It was the month of November, and he was preparing for the last session of the mission he preached in Ciudadela, on the nearby Island of Menorca, when he was transported in ecstasy before the throne of God, where a most beautiful woman clothed in glory appeared to him, her face covered by a fine veil. He understood her to be the Church, which the Eternal Father entrusted to him as a daughter.

He expressed the strong impression the scene made on his soul in these terms: “I desired to know this young Woman who came to me wrapped in mystery and hidden under a veil. Nevertheless, although veiled, I had such a sublime infused knowledge of her, I saw in her attitude such grandeur, that my happiness would be if she would accept me as the humblest of her servants and attendants.” 8

“Holy Church!” he would later exclaim. “For twenty years I sought thee: I was looking at thee but did not know thee, for thou wert hidden beneath the obscure shadows of mysterty, of figures and metaphors, and I could only see thee under the form of a being incomprehensible to me; it was thus that I saw thee and loved thee. It is thee, holy Church, my beloved! Thou art the sole object of my love!” 9

Thus began a relationship between him and the Church as a mystical person. “I am a reality, a perfectly organized moral body: my head is God made Man; my bones, my flesh, my nerves, my members are all the Angels, Saints and the just destined for glory; my soul, the spirit that vivifies me, is the Holy Spirit,” 10 she would say to him in one of his visions. These became more frequent, culminating in a spiritual espousal, in which Our Lord Jesus Christ gave the Church to him, also, as spouse.

The beautiful lady of the first manifestations was followed by Sarah, Rebecca, Esther, Judith and other prefigures of the Church from the Old Testament. In this way she transmitted her sublime mysteries to him and strengthened their bonds of union. At a certain point, the perfect archetype and most pure mirror of the Mystical Bride of Christ appeared to him, the Most Holy Virgin.

At the service of the Mystical Bride of Christ

Such profound heavenly communications made the ecclesial cause the rectrix principle of his existence: “My mission is simply to proclaim to the people that thou art infinitely beautiful and lovable, and to exhort them to love thee.” 11 With this zeal, he set out to evangelize in several cities of Spain.

The mystical experiences with the Church were at the root of his foundational plans. Sensing himself called to unite the active life with the rich contemplative tradition of Carmel, he founded two religious congregations: that of the Third Order Carmelite Brothers, abolished during the Spanish Civil War, and a feminine congregation, today divided into two branches, the Missionary Carmelites and the Teresian Missionary Carmelites.

In his pastoral work, Blessed Palau also made good use of the pen. He had already published spiritual works, such as “The Struggle of the Soul with God and Catechism of the Virtues, and others of a polemical nature in his own defence, such as The Solitary Life and The School of Virtue Vindicated. Of this time, the letters sent to his disciples, and the articles of the weekly publication El Ermitaño stand out. In them he sets forth impressive analyses and previsions regarding ecclesiastical and social events.

Of no less importance was his work as an exorcist. “I command you: expel the devils wherever you encounter them,” 12 he heard in one of his visions. He was convoked to exercise this ministry, which he did with excellent results, to the degree that the ecclesiastical authorities permitted him.

Future triumph of the Holy Church

A new phase would mark his supernatural relationship with the Mystical Body of Christ. He was in Es Vedrà, on a tempestuous morning in 1865. The peak of the rock was enveloped in a luminous cloud that transformed “the light of the sun into darkness.” 13

In the centre of it, the Church appeared to him, represented by Queen Esther. After amiable greetings, she said: “On various occasions you have given proofs of your love, of your obedience, of your fidelity, of your firmness, of your perseverance and of your loyalty to me; and I have placed my love and my trust in you. From now on, we will deal with the fate and the situation of the Roman Church and your mission in it.” 14

Thus began, in an apex of mystical union, a series of revelations regarding the internal and external evils assailing the Church and those which, in the future, would befall her. At the same time, Fr. Palau contemplated her immortal glory and definitive victory through the intervention of a man filled with the spirit of Elijah.

In this intention he addressed ardent supplications to God and offered austere penances, not neglecting to register his prophetic hopes on the pages of El Ermitaño: “If the true restoration comes, which consists in the conversion of all nations and their kings to God, the restorer cannot be a king, but an apostle; war does not convert, but destroys, and this apostle will be Elijah, the promised Elijah, no matter the name given him when he appears. Whether he is called John, Moses, or Peter matters little: the mission of Elijah will restore human society, because God in His Providence has thus ordained it.” 15

From the militant to the triumphant Church

Since his youth, Blessed Francisco Palau desired to shed his blood for the Holy Church. However, a daily martyrdom of boundless dedication was asked of him, amid misunderstandings, calumnies and sufferings…

The last years of his life were devoted to preaching, exorcism and the juridical consolidation of his foundations. His last days were spent with his spiritual sons who were caring for typhoid fever patients. Taken ill, he arrived at Tarragona in the beginning of 1872, and on March 20 he serenely departed from the Church militant to contemplate the Church triumphant without veils.

Nevertheless, like the towering Es Vedrà defying the fury of the waves, his luminous example soars above the undulations of time and makes his faith in the promise of the Saviour resound throughout history: “Thou art Peter; and upon this rock I will build My Church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it” (Mt 16:18). ◊

Notes

1 BLESSED FRANCISCO PALAU Y QUER. La vida solitaria [The Solitary Life], c.2, n.10. In: Obras selectas. Burgos: Monte Carmelo, 1988, p.212.

2 Idem, c.5, n.20, p.215.

3 BLESSED FRANCISCO PALAU Y QUER. La Escuela de la Virtud vindicada [The School of Virtue Vindicated]. L.II, c.2, n.23. In: Obras selectas, op. cit., p.252.

4 BLESSED FRANCISCO PALAU Y QUER. Carta [Letter] 101/115. Al P. Pascual de Jesús María, 1/8/1866, n.2. In: Obras selectas, op. cit., p.852.

5 Idem, ibidem.

6 Idem, n.3.

7 BLESSED FRANCISCO PALAU Y QUER. Mis relaciones con la Iglesia [My relationship with the Church], c.8, n.21. In: Obras selectas, op. cit., p.454.

8 Idem, II, n.3, p.353.

9 Idem, III, n.1, p.354.

10 Idem, c.20, n.6, p.595.

11 Idem, c.12, n.2, p.530.

12 Idem, c.8, n.30, p.459.

13 Idem, n.27, p.457.

14 Idem, n.28.

15 BLESSED FRANCISCO PALAU Y QUER. Anarquía social [Social Anarchy]. In: El Ermitaño. Barcelona. Ano IV. N.114 (12 jan., 1871); p.4.