Perhaps few things are as difficult to express in words as music! In its varied and vast scope, the universe of music amounts to an art form that, without exaggeration, can be said to verge on the infinite, for it somehow participates in the immateriality proper to spirits.

That being the case, much of the satisfaction that fills our souls when we hear a lovely melody stems from this fact: it momentarily “frees” us from the fetters of the concrete world, which keep us from being better attuned to transcendent realities.

Another difficulty arises when the topic of music is discussed: since music causes multiple impressions on those who hear it, sometimes even contradictory ones, it is hard to establish an equitable consensus in judging compositions and composers.

For example, how can it be explained that, in the Middle Ages, Pope John XXII was averse to the nascent polyphony, out of fear that plainchant would lose valued characteristics?1 Or that St. Pius X, at the outset of his pontificate, dedicated his first motu proprio to music, as an art that “is not always easily contained within the right limits”?2

And even today, how can we interpret the all-too-prevalent tendency to segregate the divine from the musical compositions used in the Liturgy?

Without aiming to reflect chiefly upon the philosophical aspects of this art form, this article will merely sketch some facets of the life-trajectory of an Italian composer, born in the second half of the 16th century, who so aptly and effectively placed his musical aptitude at the Church’s disposal: Giovanni Gabrieli.

We apologize in advance to the reader for our inability to transpose the sounds into written form… which is why most of what is presented here will only find its proper resonance if set in the tonal diapason of the Italian master’s harmonies. Thus, we even invite you to listen to a sample composition of our musical prodigy from Venice as you read this article.

* * *

Art is an indicator of a people’s prosperity! Regardless of its ambit of performance – from gastronomy to painting, from architecture to literature – when wisely cultivated, it serves as a type of banister and elevator for our senses so that, in this “valley of tears,” we may more easily discover vestiges of God.

If we cast a glance, à vol d’oiseau, at the trajectory of the Church, from its primal beginnings to 1552, likely the birth-year of Giovanni Gabrieli, it is notable how various imperatives of Christian charity gradually imbued society: human beings gradually shed their coarseness and, consequently, grew in the capacity to refine that “creative power” which is art.

Music was among the various human activities that saw advancement. It was an art never absent from the sanctuary – to add splendour and solemnity to ceremonies worthy of greater dignity – despite its winding and enigmatic course of progress.

The use of instruments in the Liturgy, however, has always generated particularly heated debate, even to this day…

Should musical instruments be sounded or silenced?

Although prominent historians such as Mario Righetti affirm that musical instruments “were probably banished from the temple because of their profane, sensual and clamorous nature,”3 the question seems to revolve around another point: perhaps the fact that humanity had become more sensual and less spiritual, more profane and less prayerful, is what prompted the production of instruments with such overtones, consequently preventing the Church from introducing them into the Liturgy much earlier.

Furthermore, it ought to be understood that musical instruments, far from being unfit for worship, have had a place in it since the primeval Old Covenant religion,4 as a means for praising God and expressing, in their own way, grace and heavenly favour. As a logical consequence, it would only seem natural for instruments to have been present in Christian worship from its inception.

International choir of the Heralds of the Gospel during a Mass in the Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary, Caieiras (Brazil)

Therefore, our Catholic soul is utterly dissatisfied when the historian simply states that “this Jewish musical-instrumental tradition did not pass on to the early Church; the apostolic writings and those immediately following them make no reference to it.”5The crux of the problem thus lies in discovering why this tradition was not carried on to the New Covenant.

One is led to believe – contrary to the dominant view – that the real reason for the absence of instruments in the Liturgy was the fact that society had been rendered brutish and coarse, to a greater or lesser degree, which kept people from conceiving music that was at once thoughtful, solemn, grandiose, and endowed with the sobriety that characterized plainchant.

In short, man hesitated to transpose his interior rapture into musical notes and feared that musical compositions would distance him from the virtue of religion.

Nevertheless, others regarded Gregorian chant as the sole expression of the Church’s universality in musical matters, thus curtailing this distinctive note. Now, as Mother and Teacher of peoples, her very richness demands that other musical styles, consonant with her, be “baptized,” particularly for sacred worship.

The career of Giovanni Gabrieli

From this angle, and in this historical context, we can better understand Giovanni Gabrieli as a key figure. Born in Venice, little is known of his childhood except that he was introduced to music by his uncle Andrea Gabrieli, with whom he studied and from whom he drew his talent.

History further records that, long before achieving fame, Giovanni studied music in Munich, Germany, with the renowned Orlando de Lassus, in the court of Duke Albert V,6 where he remained until 1579.

Returning to his hometown, he took over as head organist at San Marco Basilica, following the resignation of Claudio Merulo – incidentally, a fine composer and likely responsible for the fame that was beginning to distinguish the Venetian school. The following year, possibly 1585, upon the death of his uncle Andrea, Giovanni Gabrieli additionally assumed the prestigious position of chief composer.

Early in his career, Gabrieli’s concern was to publicly recognize the calibre of his master and mentor by compiling and disseminating countless works that his uncle had composed, paying him the tribute he owed for the training he had received. In his own words, he considered himself “almost a son” of Andrea.

Although Giovanni composed music in keeping with the styles of the time, he was particularly inclined toward sacred music, which explains why his entire early repertoire was vocal, since voices and instruments were still separated by an insurmountable barrier in sacred settings.

In fact, this was the situation in the historical period of the 16th century: “It was in Rome, shortly after the Council [of Trent], that Palestrina and his rival Victoria lived, initiators of a church music that would increasingly move away from the old polyphony to seek new paths. Until then, priests and theologians had strongly resisted anything that might deviate from the rule that only the human voice was worthy to pray to God: musical instruments seemed theatrical to them, prone to sensuality and pride.”7

However, in Giovanni’s eyes, this was a mistaken conception. Sacred vocal music, when combined with instruments, could soar to new heights of spirituality by externalizing “truths of Faith” that demand more grandeur and power; or, when nuanced by the strains of the organ and backed by additional instruments, it would be capable of expressing deeper and more tender sentiments, unreachable by the limitations of the human voice and the mere text.

In the person of this Venetian genius, humanity seemed to voice its desire to intone, from within the temple, a new song to the Lord with the psalmist David, accompanied by musical instruments (cf. Ps 33:3).

Piazza and Basilica of San Marco, by Canaletto

New harmonies resound in the sanctuary

Like the harpist of Scripture, Giovanni Gabrieli was not afraid to bridge the gap that long separated the human voice from musical instruments in sacred ambiences. For this undertaking, he chose as the stage for his innovative and rich compositions the centuries-old walls of the poetic Basilica of San Marco in Venice, whose interior structure, chiselled by the delicacy and grace of Sansovino,8 favoured the resonance of his novel harmonies.

There, capitalizing on choir stalls that stood face to face, he was able to create impressive sonorous effects by positioning his musicians in two groups, which enabled him to make the most of a peculiar dynamic through successively strong and weak sounds. In this way, a choir or instrumental group was heard first on one side, followed by a response from the second ensemble on the other. There might also be a third group located near the altar, in the centre of the church, to “work out” the most important passages of the composition.9

The result was that, when correctly situated, the instruments could be heard with perfect clarity from far away. Thus, scores that looked strange on paper – for example, indicating a single stringed instrument being played against a sizable group of wind instruments – resounded in perfect balance in the interior of San Marco Basilica, thanks to the acoustics being mapped out by the composer’s own inspiration! The works In Ecclesiis and Sonata pian’ e forte are notable examples of this.10

The myths surrounding the use of instruments in the Liturgy were thus effectively dispelled: “One thinks of associating it with the glorification of God. From then on, its triumph was assured, especially the triumph of the typical church instrument: the organ, which made its appearance everywhere.”11

Thus, at least as far as sacred music was concerned, Gabrieli’s genius would come to bear a weighty influence on the history of the art.

Diffusion throughout Europe

The Venetian master’s standing gained further prominence among the European elite when he became the organist at the Scuola Grande di San Rocco – a post he held until his death – since the Church of St. Roch featured the most prestigious and wealthy Venetian confraternity, rivalled only by that of San Marco in the splendour of its musical ensembles.

Thus, the tendencies of Baroque music would ready to be echoed, reconciling the human voice with the instrument, and not only with the organ, but even with the orchestra.

Naturally, several other European musicians, especially from Germany, were eager to travel to Venice to become acquainted with new knowledge. As a result, several students and admirers of Gabrieli became propagators of his compositions in other countries.

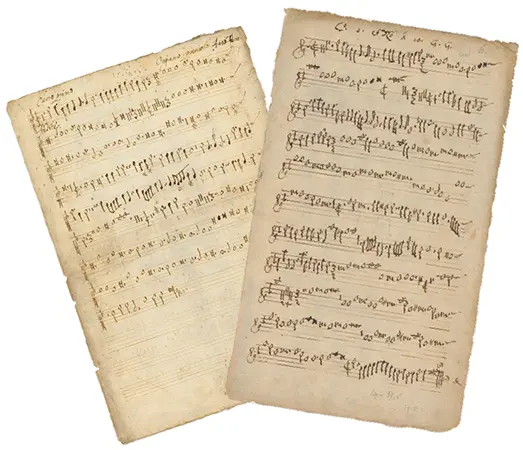

Manuscript score of the work “Audite princeps”, by Giovanni Gabrieli – Library of the University of Kassel (Germany)

Among his students, Heinrich Schütz was particularly notable and perhaps one of the greatest glories that music owes to Gabrieli. It was he who adapted the Italian style of madrigals and sacræ symphoniæ to the genuinely German spirit.

Sounds that contribute to the grandeur of worship

Now that centuries have elapsed, and the serenity of hindsight allows us to appraise events with greater accuracy, we see that the insight of Gabrieli’s soul was assertive: far from having a detrimental effect within the walls of sacred places, being somehow considered sensual or proud, musical instruments actually contribute to the grandeur of worship.

Today, what faithful soul does not relish being transported to a more joyous and beneficial reality at the sound of Gabrieli’s sacræ symphoniæ, for example, reverberating through the majestic naves of St. Peter’s Basilica during the Easter Vigil, while the Pope moves from the presbytery to the baptismal font to bless the water that will transform poor humans into children of God?

At the sublime moment of Baptism, on the holiest of nights, the grand notes and musical intervals of Gabrieli – genius of the art – emphasize the dignity of the Sacrament, completing the scene. ◊

Notes

1 Cf. COMBARIEU, Jules. Histoire de la musique. 8.ed. Paris: Armand Colin, 1948, t.I, p.383.

2 ST. PIUS X. Tra le sollicitude.

3 Cf. RIGHETTI, Mario. Historia de la Liturgia. Madrid: BAC, 2013, v.I, p.1133.

4 It is even interesting to note a certain exorcistic character inherent in instrumental music: it was tunes from David’s harp that freed Saul from the evil spirit (cf. 1 Sm 16:15-23).

5 RIGHETTI, op. cit., p.1132.

6 Albert V, Duke of Bavaria, was one of the leaders of the Catholic Counter-Reformation against the German Protestants. As an influential maecenas, he was a great art collector and granted the musician Orlando de Lassus a prominent place in his court.

7 DANIEL-ROPS, Henri. História da Igreja de Cristo. A Igreja dos Tempos Clássicos (I). São Paulo: Quadrante, 2000, v.VI, p.129.

8 Andrea Contucci, known as Andrea Sansovino, was an Italian architect and sculptor who became influential in art during the High Renaissance period. The choir stalls of St. Mark’s Basilica adorned with three reliefs sculpted by him, provided the setting for countless interpretations by the composer Giovanni Gabrieli.

9 Although this polychoral style – cori spezzati – had been used elsewhere for decades, Gabrieli’s skill made it remarkably successful.

10 There are at least a hundred compositions by Giovanni Gabrieli: two sets of sacræ symphoniæ, as well as canzoni, sonatas and concertos. Many of his works were published posthumously.

11 DANIEL-ROPS, op. cit., p.129.