Entrenched in a false conception of Jesus’ mission, the Apostles failed to heed His voice. Let us be vigilant so that the same does not happen with us.

Gospel of Second Sunday of Lent

2 Jesus took Peter, James, and John and led them up a high mountain apart by themselves. And He was transfigured before them, 3 and His clothes became dazzling white, such as no fuller on earth could bleach them. 4 Then Elijah appeared to them along with Moses, and they were conversing with Jesus.

5 Then Peter said to Jesus in reply, “Rabbi, it is good that we are here! Let us make three tents: one for You, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” 6 He hardly knew what to say, they were so terrified.

7 Then a cloud came, casting a shadow over them; from the cloud came a voice, “This is My beloved Son. Listen to Him.” 8 Suddenly, looking around, they no longer saw anyone but Jesus alone with them.

9 As they were coming down from the mountain, He charged them not to relate what they had seen to anyone, except when the Son of Man had risen from the dead. 10 So they kept the matter to themselves, questioning what rising from the dead meant (Mk 9:2-10).

I – God did not Spare His Own Son

At the outset of Lent, a time dedicated to penance, the tone of the readings for the Second Sunday takes us by surprise. After a week centred on the call to conversion and the fight against temptations, we are invited to contemplate the Transfiguration of Our Lord Jesus Christ—a moment of glory and splendour. Why this change of perspective? In focusing on this mystery, the Church wants us to consider what lies behind the external appearances of life, for these are actually only a portion of reality, and not the entire and absolute reality, which is hidden to the senses. An analysis of the various texts of today’s Liturgy, within the context of the singular event of the Transfiguration, makes this principle very clear.1

At the root of the promise, God demands abnegation

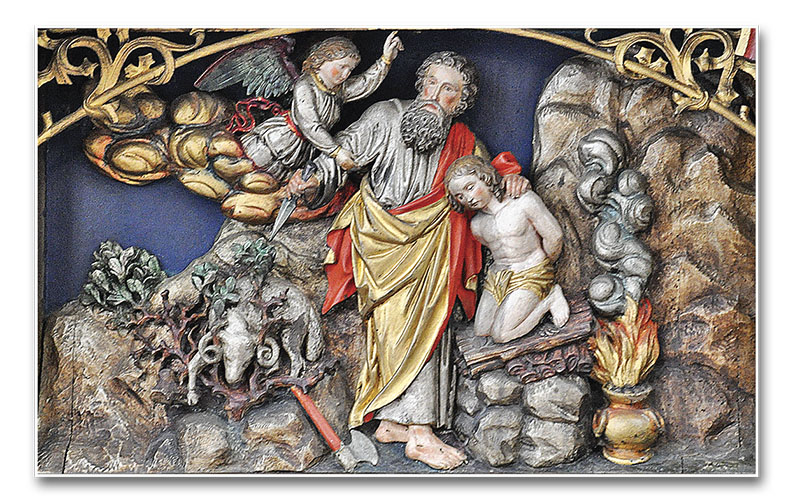

The first reading (Gn 22:1-2.9a,10-13,15-18) brings us an episode from the dawn of the Chosen People, one which marked salvation history. Abraham, an Aramaean, had reached old age along with his wife Sarah, hitherto childless. Notwithstanding, God had promised him that he would give origin to an abundant progeny, more numerous than the stars of the sky (cf. Gn 15:5), a true nation (cf. Gn 12:2). They would not be a common people, for from their ranks would be born the Redeemer, Jesus Christ. The Lord later announced that Sarah would give birth to a son (cf. Gn 17:16). Abraham believed, and, despite his advanced age, Isaac was born. This son—winning, intelligent and intuitive, as is deduced from the biblical narrative—grew up surrounded by the affection and entire admiration of the father who had earlier resigned himself to having no heir.

At a certain moment, God chose to test Abraham, for every gift or privilege that He grants requires the retribution of sacrifice and abnegation. And the greater the gift, the greater the giving required of the creature. Thus, to be worthy of such a high calling, and to receive the reward, the light and the glory of being the ancestor of the Messiah—a Man Who is also God—Abraham had to undergo a trial to prove his complete flexibility to the designs of Providence. Without this merit, there would be inadequate foundation for a vocation of such grandeur.

A heart-rending scene marked by an axiological trial

When Isaac reached roughly nine years of age, God demanded that Abraham offer him in sacrifice. The patriarch cherished the child dearly as his successor and the son of the blessing received from the Lord’s hands. Yet now the Lord was asking for him back. If today we understand that surgeons normally lack the necessary emotional stability to operate on their own children, how could a father be expected to carry through with the sacrifice of one who was flesh of his flesh? However, Abraham did not waver, and acted with the conviction that he was doing God’s will.

Genesis does not tell of Abraham’s interior affliction, nor of the perplexity and axiological difficulty that this situation occasioned, but he evidently would have felt a greater sorrow than if he himself were to be offered as the victim, and his son Isaac were to kill him and cast him into the fire to be consumed. How was he to confide in God’s promise while surrendering his only son? Was the Lord displeased with him, to the point of taking away his heir? After all, every man conceived in original sin has imperfections; had he committed some hidden fault? In the throes of untold torment, he made the mountain ascent. He likely revealed his distress to no one, guarding in his heart the tragedy that was unfolding between God and himself.

Abraham invited Isaac to accompany him up the hill to offer a victim, and brought along everything that was needed: the wood, the fire and two servants as assistants (cf. Gn 22:3). Now, the child had reached an inquisitive age, and, possessing the logical intelligence so common to the Hebrews, there was something he did not understand, so he inquired: “Behold, the fire and the wood; but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?” (Gn 22:7). Isaac’s father, who had always affectionately resolved his son’s doubts, and took every opportunity to transmit his knowledge to him, was obliged to respond: “God will provide” (Gn 22:8). As they walked on, he spoke lightly with the child, but his heart was gripped with anguish. Presumably, Abraham would have preferred to die on the way, before even reaching the foot of the mountain, and yet, he felt God giving him the strength to carry on. Arriving at the place indicated by God, he prepared the wood, while Isaac, perhaps, asked one last time about the victim. Finally, Abraham bound him and laid him upon the altar. At that moment, Isaac, who had inherited his father’s character, and had also received his faith, immediately understood everything, and surrendered himself in utter silence, obedience and docility. What a heart-rending scene! Abraham was ready to stain his hands with the blood of his only descendant, who was a gift from Heaven and the promise of his posterity.

But God did not allow the boy to be killed, for He did not require this offering. What He wanted, rather, was the sacrifice of Abraham’s entire conformity to His will, his total generosity despite deeply disturbing appearances, and, at the same time, Isaac’s uncomplaining submission to immolation. As Abraham raised the knife with entire faith, ready to plunge it into Isaac, an angelic voice called out: “Abraham, Abraham! […] Do not lay your hand on the boy […]. I know now how devoted you are to God, since you did not withhold from Me your own beloved son” (Gn 22:11-12). It was the order that he longed to hear, to call off the tragic moment of execution. Yet, just as man is condemned by his intentions—if he plots a crime, for example, but circumstances impede him from carrying it out, he sins interiorly—, Abraham “was justified by works” (Rom 4:2). Indeed, not only had he accepted God’s decree, but he had also taken all steps toward consummating the sacrifice of Isaac. In return, he received back his son whom he had already relinquished, and joyfully gave thanks to God.

God, who saved Isaac, sacrificed His own Son

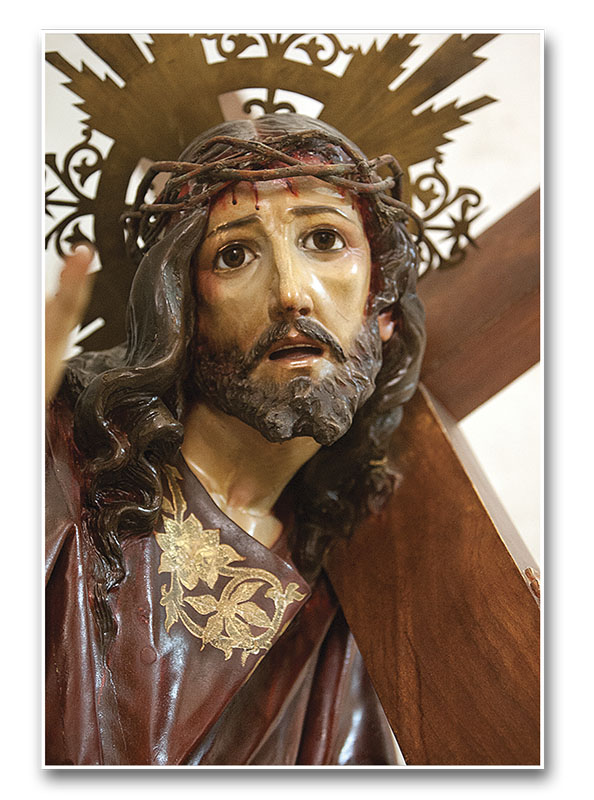

And “as Abraham looked about, he spied a ram caught by its horns in the thicket. So he went and took the ram and offered it up as a holocaust in place of his son” (Gn 22:13). This episode points to the future ransom of the firstborn prescribed by Mosaic Law after the departure from Egypt (cf. Ex 13:13; 34:19-20), when the blood of the unblemished lamb, marking the doorposts and lintels, would preserve the firstborn of the Chosen People from the exterminating Angel (cf. Ex 12:5-13). This animal, in reality, was a symbol of the true Lamb, the Lamb of God. For, in order to manifest His love for us, the Lord, Who spared the life of Abraham’s son, does not save that of His own Son, nor deliver Him from the most ignominious of executions, namely, death on the Cross. Indeed, what occurred with Abraham did not repeat itself on Calvary. There, God “did not spare His own Son but handed Him over for us all” (Rom 8:32), as the Apostle affirms in the second reading (Rom 8:31b-34). On Golgotha, we behold the Only-begotten Son of God crowned with thorns, scourged, despised, and outraged by the depravity of the executioners, who spat upon Him. Christ was one wound from head to foot, so that all His bones could be numbered (cf. Ps 21:18). When the moment of His crucifixion came, having completed the Via Sacra, falling three times beneath the weight of the Cross, the Only-begotten Son of God was slain. He was annihilated for us, for He desired our salvation: “I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but that the wicked turn from his way and live” (Ez 33:11).

What were God’s designs in all of this? Why did He submit Abraham to this trial and allow His own Son to be immolated? Let us consider an infallible principle: since God is Goodness in essence, He cannot sin, 2 and whenever He acts, it is with some benefit in view. If He put the patriarch to the test and had His Son undergo the horrors of the Passion, it was for the good. Does the Father not seek the best for Him of Whom He declares, in the Gospel: “This is My beloved Son”? But how can we comprehend that the Cross be an excellent thing? How to recognize that the martyrdom of a Son is the best for Him? Without the aid of God’s grace, human reason is incapable of grasping such beauty.

In contemplating the Transfiguration of the Lord in mid-Lent, the Church desires to give us a new outlook. Just as the Redeemer transfigured Himself to give strength to the Apostles, and lead them to acknowledge that He was God, and would continue being so even crucified and dead, we must also learn that suffering and the cross, as stark as they may seem, essentially contain a divine favour and a type of resurrection, brilliance and glory.

II – A Deficient Image of the Saviour

The Transfiguration of the Lord took place on an occasion of fundamental importance. The Gospel of St. Matthew narrates that this mystery occurred six days after the confession of Peter (cf. Mt 17:1), which had clarified to the Apostles that Our Lord was true God and true Man (cf. Mt 16:16). In consequence of the union between the divine and human nature that exists in the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity, Jesus is entirely Man—and, as such, felt hunger, thirst and the effects of other necessities—, but everything in Him is adorable, for He is God. In an apparent paradox with the recognition of His divinity, Christ had foretold His Passion in unmistakable terms (cf. Mt 16:21)—an announcement that the Twelve had not assimilated, for they still harboured a series of illusions regarding the conquest of temporal power in Israel. Throughout those days, they must have lengthily discussed the extraordinary scope of the supposed victory, and the political, social and economic triumphs that would be its fullest expression. Men of every era dream of such successes, inebriating themselves with what is, in fact, only the rest that shall be added unto us, if we but seek the essential, as Our Lord taught: “seek His kingdom, and these things shall be yours as well” (Lk 12:31). But the disciples had not learned this lesson, despite all the doctrine the Divine Master had already given them, and they still entertained expectations of a earthly kingdom, in which everything would be marvellous. After all, is anything difficult for a God made Man, possessing dominion over nature? Jesus had the solution to every problem, and eternal happiness would therefore be established over the face of the earth! The apostles’ tendency, then, contrary to what Our Lord had told them, was to believe that the phase of suffering had ended… What an illusion! For it is only through the cross that one reaches the light: Per crucem ad lucem!

Chosen to sustain the faith of the others

2 Jesus took Peter, James, and John and led them up a high mountain apart by themselves. And He was transfigured before them…

Jesus chose three especially beloved Apostles to witness the Transfiguration, so that they could later testify to His divinity. When they would contemplate Him praying and sweating Blood in the Garden of Olives. And later, facing the terrible episodes of His Passion and Death, they would need the remembrance of this mystical experience so as not to lose their faith. With this support, not even a reality as tragic as that of Gethsemane could shake the total certainty acquired on Tabor, where He revealed His true self to them. In this way, they would understand Who it was that that suffered: God Himself. Our Lord, therefore, wished to assure the Apostles that all future events would be for His glory.

Glorious manifestation

3… and His clothes became dazzling white, such as no fuller on earth could bleach them.

It can be deduced from this verse that, even at that time, there were people specialized in meticulously cleaning clothes. But the Evangelist declares that nowhere on earth—which, in a prophetic way, encompasses all of history—could anyone make a garment as white as His. The transformation of the appearance of His clothes is a clear sign that Our Lord, as St. Thomas3 states, outwardly revealed the glory of His Soul, for fleeting moments, making clarity, a characteristic of glorious bodies shine forth. Given that the soul is the form of the body, the soul’s glory redounds in the same for the body. Now, if, in virtue of the hypostatic union, Our Lord’s Soul was created in the beatific vision, His Body would normally enjoy the same perfection. Yet Christ suspended, for Himself, this law He had established, assuming a mortal body in order to accomplish the Redemption. Nevertheless, at several moments in His life He possessed specific properties of the glorious body, in a miraculous way. He displayed subtlety, at birth, in passing from Our Lady’s interior cloister into her arms, without causing her the least harm; impassibility, when He escaped, untouched, from those who sought to stone and kill Him in Nazareth (cf. Lk 4:29-30); agility, in walking upon the waters (cf. Mt 14:25); and clarity, as we saw, in the scene of the Transfiguration, where the whiteness of the garments provided “a beautiful idea of the glory that is promised to us. It had such brilliance that even the sun was obscured by it! And what profusion, for having filled the entire Body, it even shone through the garments!” 4

The representatives of prophecy and the Law pay homage to Jesus

4 Then Elijah appeared to them along with Moses, and they were conversing with Jesus.

According to the Law of Moses, two witnesses sufficed to establish legal certainty (cf. Dt 17:6; 19:15). Thus, during this extraordinary episode, Our Lord was joined by Elijah and Moses. It was incumbent upon the first—as a symbol of the line of the prophets of the Old Testament, and its greatest exponent—to testify that He was God, the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity Incarnate. And the presence of Moses made it clear that the legislation He promulgated was, in fact, inspired by the Word. Therefore, the Redeemer did not come in opposition to the Law or the prophets, but was the realization of all the oracles, and the ultimate and perfected complement of the Old Law.

Overwhelmed at the splendour of the grace received

5 Then Peter said to Jesus in reply, “Rabbi, it is good that we are here! Let us make three tents: one for You, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” 6 He hardly knew what to say, they were so terrified.

The scene was so grandiose that St. Peter was overwhelmed. Authors frequently interpret the request of making three tents as a desire to prolong that marvel indefinitely. This observation may be valid, in a certain sense, but the evangelical text clearly states that he was terrified and hardly knew what to say. Communicative as he was, he felt impelled to comment. It would seem more appropriate, then, to consider that Peter was bewildered because he saw the Word without knowing Its interpretation; but the light necessary for this was soon to come from above.

The Father loves the Son entirely

7 Then a cloud came, casting a shadow over them; from the cloud came a voice, “This is my beloved Son. Listen to Him.”

When we love a particular creature, we are attracted by the good that exists in it. If, for example, we are inclined to a particular landscape, it is because we see the beauty and the good that God has placed in it. The perfection of the landscape precedes the movement of our will, which moves outward toward that form of pulchritude. However, with God, the reverse occurs. His love causes the good to penetrate into that which He loves, thus producing the goodness of beings. Now, this charity—which, in Him, is infinite—was exhausted in His Only-begotten Son, in Whom He was well pleased, as another Evangelist states (cf. Mt 17:5). God loved Him superlatively, for He was His only Son.

We, mere creatures, are loved by the Creator and receive the infusion of His goodness, but our response is never on a par with these gifts; that is, we always fall short of what we should give. Yet He loves us, notwithstanding. And He would love us all the more if our restitution were greater! Our Lord Jesus Christ, in contrast, gave absolutely everything possible in retribution to the Father, at every instant, thus eliciting an altogether singular love that would prompt the words: “This is My beloved Son.” As a result of this love, Jesus is He Who sums up and encompasses within Himself everything that came from the divine hands. On the Cross, in completely restoring the order of creation, He conquered, as Man, the title of our King, Saviour, and Redeemer. These, as God, He already possessed, as St. Cyril of Alexandria reminds us: “being God from all eternity, He ascends from our limited condition to the perfect glory of the divinity.” 5 Therefore, the Father gives Him every praise and honour. In short, He willed the torments of the Passion for Christ because He desired to raise Him to the fullness of glory.

Suffering passes

8 Suddenly, looking around, they no longer saw anyone but Jesus alone with them. 9 As they were coming down from the mountain, He charged them not to relate what they had seen to anyone, except when the Son of Man had risen from the dead. 10 So they kept the matter to themselves, questioning what rising from the dead meant.”

According to St. Matthew, the Apostles fell prostrate when they heard the voice of the Father (cf. Mt 17:6). How powerful this voice must have been; what force it must have had, penetrating them to their very bones! Every aspect of this revelation was meant to encourage the Apostles to consider the Master as a divine being and to realize that it was imperative to listen to Him, even if He were to proclaim, shortly afterward, that He would die and resurrect on the third day. But Our Lord wanted to show them, above all, that the pains of Calvary would be fleeting.

In the episode of the Transfiguration, He makes it clear that, while eliminating suffering is impossible, God also does not demand what is beyond our strength: “Deus qui ponit pondus, supponit manum — God supports with His hand the burden He lays,” says the proverb. Suffering lies along the path of sanctity and of sin alike. But along the first it is always gentler, and every suffering endured well eventually results in victory, as St. Alphonsus Maria de Liguori points out: “We must suffer, and all must suffer; both just and sinners carry their crosses. He that carries it patiently is saved; he that carries it impatiently is lost. […] He that humbles himself under tribulation, and is resigned to the will of God, is wheat for Paradise; he that grows haughty and is enraged, and so forsakes God, is chaff for Hell.” 6 The glory that awaits us in eternity, in the joy of the beatific vision, is so great that it justifies all sufferings that might befall us. In the words of the Apostle: “the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory that is to be revealed to us” (Rom 8:18).

This Gospel helps us to put the problem of suffering in focus. When we are beset by a tragedy or a setback that we cannot comprehend, we ought to rejoice, for it indicates that we bear the sign of the predestined in our souls: “Just as God has treated His beloved Son, so does He treat everyone whom He loves, and whom He receives as His child.” 7 Dilemmas, disappointments, misunderstandings, health problems, family tensions, financial difficulties, and calamities are permitted by Providence for our good. This is why, in the second reading, St. Paul asks: “If God is for us, who can be against us? He Who did not spare His own Son but handed Him over for us all, how will He not also give us everything else along with Him?” (Rom 8:31b-32). “Everything” also includes suffering. Let us, therefore, be glad, for every step of our Lenten journey brings us toward the Crucifixion of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Confident that Providence will never forsake us, let us surrender ourselves entirely into His hands—like Abraham, and like the God-Man Himself—, so that He may do with us whatever He wills.

III – Let Us Make an Oblation of Whatever Separates Us from God!

In view of the teachings of this Liturgy, we must not forget that the love the Father has shown us in the mactatio — immolation—of His Son deserves reciprocity. God expects from each one of us the sacrifice of detachment from whatever separates us from the true course, along with any cares that bind our heart to something other than Him, and docility to His will. Having called us to holiness, He wants us entirely. He desires that we remain, like Abraham, with our dagger steadfastly raised. If Abraham was ready to offer up Isaac, how can we be unwilling to renounce that which is an obstacle to salvation and to our perfect relationship with the Lord? What great profit we would gain in making the fervent resolution to lay all of our rebelliousness on the wood, bring the knife down upon it, and then set it afire in oblation to God! We, like Abraham, would thus free ourselves from disordered esteem for creatures.

Many have praised this holy patriarch’s faith, which is truly deserving of all esteem; but perhaps more beautiful still is his obedience, reflected in that of his son Isaac. “Obedience,” St. Ignatius of Loyola affirms, “is a holocaust in which the whole man offers himself without the slightest reserve in the fire of charity to his Creator and Lord […]; it is a complete surrender of self, by which a man dispossesses himself to be possessed and governed by Divine Providence.” 8 Obedience practised with this radicality results in the realization of promises, because God assures Abraham: “I swear by Myself, declares the Lord, that because you acted as you did in not withholding from Me your beloved son, I will bless you abundantly and make your descendants as countless as the stars of the sky and the sands of the seashore; your descendants shall take possession of the gates of their enemies, and in your descendants all the nations of the earth shall find blessing—all this because you obeyed My command” (Gn 22:16-18). How delighted we would be to hear the voice of God telling us: “Since you have renounced all your attachments, burned and laid them in sacrifice on an altar, I will bless you, because you have obeyed Me.” Obedience is one of the virtues that most pleases God; not obedience made up of outward appearances, but the kind springing from the depths of the heart, like that of Abraham: this is authentic obedience.

Again, in the second reading, St. Paul encourages us to adopt this attitude, for we have an intercessor in Heaven: “Christ Jesus it is Who died—or, rather, was raised—Who is also at the right hand of God” (Rom 8:34). Abraham did not have Our Lord, or even Our Lady, to plead with the Father on his behalf. Our situation is far superior to the patriarch’s, for we enjoy the intercession of an absolute Advocate, and of a Mediatrix whose impetration is omnipotent, which should fill us with confidence. But, let us not forget: “noblesse oblige — nobility obliges.” Gifted with so many privileges, our response should even greater than his.

In the Gospel, the voice of the Father exhorts us: “Listen to Him!” Let us remember Our Lord’s teaching: “If any man would come after Me, let him deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow Me” (Lk 9:23). This cross is not heavy; rather it eases the burdens of our conscience. It means obeying God’s will. The Second Sunday of Lent encourages us to keep in sight that which nourishes our faith, increases our capacity to suffer and supplies us with joy amid every torment. ◊

Notes

1 For other commentaries on this theme, see: CLÁ DIAS, EP, João Scognamiglio. Gospel Commentaries for the Second Sunday of Lent–Years A and C, in Volumes I and V respectively of the collection: New Insights on the Gospels. Gospel Commentaries for the Feast of the Transfiguration of the Lord–Years A, B and C, in Volume VII, from the same collection. Como será a felicidade eterna? In: Arautos do Evangelho. São Paulo. N.74 (Fev., 2008); p.10-17; A Transfiguração do Senhor e nossa santificação. In: Arautos do Evangelho. São Paulo. N.8 (Ago., 2002); p.5-10.

2 Cf. ST. THOMAS AQUINAS. Summa Theologiæ, I, q.25, a.3, ad 2.

3 Cf. Idem, III, q.45, a.2; a.1, ad 3; q.28, a.2, ad 3.

4 BOSSUET, Jacques-Bénigne. Ier Sermon pour le II Dimanche de Carême. In: Œuvres choisies, vol. VI. Versailles: Lebel, 1822, p.283.

5 ST. CYRIL OF ALEXANDRIA. Quod Unus sit Christus, 771b In: Deux Dialogues Christologiques. Paris: Cerf, 2008, p. 491 (SCh 97).

6 ST. ALPHONSUS MARIA DE LIGUORI. Pratica di amar Gesù Cristo, c.V. In: Opere Ascetiche, vol. I. Roma: Ed. Redentoristi, 1933, p.40.

7 Idem, ibidem.

8 ST. IGNATIUS OF LOYOLA. Carta 83: A los Padres y Hermanos de Portugal (26/3/1553). In: Obras Completas. Madrid: BAC, 1952, p.838.