Out of the mists of the improbable, a beautiful garden sprang up in the Land of the Rising Sun, planted to give Our Lady, not flowers of this world, but souls for her Reign.

What would the superior of a Franciscan friary in Poland think if one of his friars expressed the desire set out on a mission in Japan to preach the Gospel to the people of that land? At first he might even take the proposal naturally. And what if his subordinate also added the plan of publishing a Catholic magazine in Japanese – without knowing a single word of that language or having a translator at his disposal – and of founding, not a simple friary, but a veritable city consecrated to Mary Immaculate, with the intention of producing a movement of mass conversions? And if, before evaluating the possibilities for the realization of such a project, the friar were to declare that he had not a single acquaintance in Japan, nor the necessary material means, but only God’s assistance? “Madness!” would be the most likely response of the superior.

But what if this friar were St. Maximilian Kolbe? In that case, the superior would have to kneel down and give thanks to Our Lady, certain that it was She who had stirred such a noble desire in the soul of that man!

After all, in 1917, the Saint had already created in his native Poland, the Militia of the Immaculata, an association whose objective was the conversion of sinners and the sanctification of all. In 1922, he also launched the magazine Knight of the Immaculata, a publication with modest beginnings but which eventually reached a circulation of one million copies. In 1927, he had also founded the Niepokalanów (City of the Immaculata), a continually growing Franciscan monastery.

Intending to accomplish the same in the Land of the Rising Sun, he approached the Father provincial, Fr. Czupryk, who presented the consultation to the other superiors. On January 17, 1930, the project was approved, and St. Maximilian departed for Japan.

The apostolate in Japan begins

After a visit to Lourdes and Lisieux, to request the help of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St. Therese of the Child Jesus, on April 24, 1930, Fr. Kolbe and two other friars finally beheld the cherry blossoms and bamboo huts of Nagasaki.

They went to the cathedral to meet the local bishop, Most Rev. Hayasaka, who received them warmly. The prelate was very pleased with the missionaries’ arrival, among other reasons because the seminary’s chair of philosophy was vacant and Fr. Kolbe was a doctor in that discipline. It was a perfect opportunity: the Bishop would be able to supply his need for a professor, while the saintly Franciscan would find assistants in the translation of his articles into Japanese!

The first dwelling of the three friars was a precarious hovel near the cathedral, which allowed mosquitoes and rain to enter in summer, as well as wind and snow in winter. Added to the many difficulties they faced, they had difficulty adjusting to the local diet; Fr. Kolbe’s health, debilitated by the tuberculosis suffered years earlier, was worse than ever; they had yet to learn the Japanese language and customs, and their financial resources were few.

It seemed impossible that their projects would come to fruition, but reality proved otherwise. Great supernatural works need to be founded upon many sufferings accepted with resignation, and these three “Knights of the Immaculata” were the men of faith called to lay the solid foundations of this undertaking.

Having decided to publish the first issue of the magazine as early as May, less than a month after their arrival in Nagasaki, they prayed unceasingly and their prayers were soon heard: a wealthy Catholic in the city provided them with a fully equipped and modern printing shop. Other people also made donations or offered help. A Japanese Methodist volunteered to translate the articles that St. Maximilian wrote in Latin into his own language, and he was so taken with these writings that he converted to the Catholic Church and joined the Militia of the Immaculata!

Thus, in the month foreseen, the first edition of Mugenzai no Seibo no Kishi – Knight of the Immaculata – was published, with ten thousand copies and, despite many difficulties, the magazine grew over the course of the year. St. Maximilian then decided to initiate the second part of his plan.

The Garden of the Immaculata

The resources available to him to purchase a piece of land for the future “City of the Immaculata” did not allow Fr. Kolbe to acquire the property that seemed the most suitable to him. This forced him to turn his attention to the outskirts of Nagasaki, where prices were more affordable.

His choice fell on the suburb of Hongochi, on the slopes of Mount Hikosan, where a five-hectare property was for sale. Despite its remoteness, the place offered a panoramic view of Nagasaki that reached as far as the sea, as it was at a higher level.

The building of the “city” began: a wooden house, a chapel, a workshop for the printing equipment, a centralized electric station and a large hall where meetings were held and catechism classes were provided for the local people. Finally, on May 6, 1931, the missionaries were able to move into the new Mugenzai no Sono, a poetic expression that means Garden of the Immaculata. Another dream had been transformed into reality!

The apostolic efficacy of the “madman of the Immaculata” soon became evident: at that time there were 100,000 Catholics in Japan, and the magazine had a monthly circulation of 50,000 copies, making it the largest Catholic periodical in the country!

Numerous conversions took place. One day, for example, the superior of a Buddhist monastery in Kyoto knocked on the door of Mugenzai no Sono. The latter, impressed by the life of the missionaries, invited Friar Maximilian to visit his community. Maximilian accepted and brought the light of faith to that place: before he left, his host told him that from now on he would not accept anyone into the monastery who was not willing to know and love Mary, the Mother of God!

Unscathed in the atomic blast

Unfortunately, Fr. Kolbe could not continue his beneficial work in Japan for long: in 1936, he was forced to leave the country to take care of his foundation in Poland. He would never return… Detained for three months by the Nazis in 1939 and imprisoned again in February 1941, on August 14 of the same year he died in the concentration camp of Auschwitz, offering his life to save another prisoner, the father of a family, and in holocaust to God for the greatest possible success of his apostolate.

St. Maximilian’s death coincided with the moment when a great danger was threatening to destroy everything he had accomplished: the Second World War. In Poland, all the members of the Militia of the Immaculata had to disperse to avoid arrest by the Nazis. Some were also killed, joining their founder in heavenly glory.

In Japan the situation became difficult to sustain: the Militia had not yet acquired sufficient strength to withstand the hardships brought on by the war, and moreover it found itself orphaned, without the support of Fr. Kolbe. Nevertheless, the friars did not abandon the Mugenzai in Sono and continued to do whatever apostolate they could.

The disaster that struck on August 9, 1945, however, seemed capable of destroying all hope: the explosion of the atomic bomb in the city of Nagasaki, where the disciples of Fr. Kolbe were carrying out their apostolate…

Was everything finished? Not at all! God writes straight with crooked lines, as the proverb says. Often the Lord allows events that are incomprehensible to human eyes and which, by some mysterious design, seem to run counter to His own plans. Nevertheless, the Saints and the prophets are able to discern something of these divine mysteries, although they are unable to clearly see all their consequences.

Protected from the expansive shock of the atomic explosion not only by Mount Hikosan, but above all by its founder, the Garden of the Immaculata remained intact: it suffered only a few broken glass panes, without any damage to its inhabitants!1 It is clear that the choice of the site for Mugenzai in Sono, fourteen years earlier, was not something merely natural: the hand of God had designated that place so that, even after the destruction of Nagasaki, the work of the “madman of the Immaculata” would remain standing – until our days! ◊

Short Biography of St. Maximilian Maria Kolbe

Rajmund Kolbe was born on January 8, 1894, in Zdúnska Wola, Poland. An exemplary child, at the age of twelve he had a vision: he contemplated the Blessed Virgin Mary, who offered him two crowns, one red and the other white, from which he could choose. The red crown symbolized martyrdom, and the white one, purity. The boy decided to take both. He thus had a clear idea of what his destiny would be.

He entered the Franciscan Order and, in 1910, took his vows, receiving the name Maximilian. In 1917 he founded the Militia of the Immaculata, aimed at the conversion of sinners and spreading devotion to the Blessed Virgin. He published countless articles in defence of the Faith, in several languages. He carried out his apostolate in Poland, Japan and India.

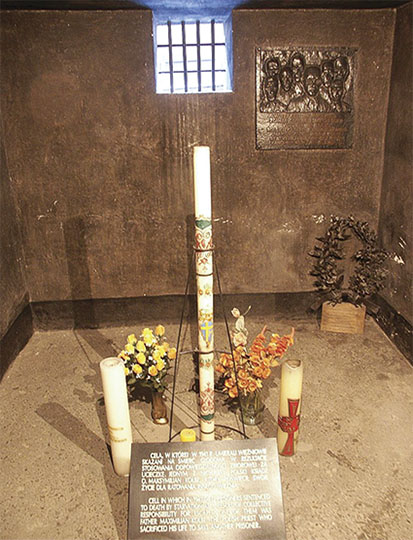

On February 17, 1941, St. Maximilian was arrested and transported to the concentration camp of Auschwitz. In July of the same year, one of the prisoners escaped, and the camp commandant decided to sentence ten other inmates to death by starvation in revenge. Among them was a family man named Franciszek Gajowniczek. Seeing that he was lamenting the fate of his wife and children, St. Maximilian offered to die in his place.

When after two weeks without food or drink the Saint was still alive, he was given a lethal injection. Thus the man of God received the red crown of martyrdom.

He was canonized by Pope John Paul II on October 10, 1982.

Notes

1 Cf. RICCIARDI, OFM Conv, Antônio. Beato Massimiliano Maria Kolbe. Roma: Edizioni Agiografiche, 1971, p.188; LORIT, Sergio C. 16670 Quem era? São Paulo: Cidade Nova, 1966, p.121.