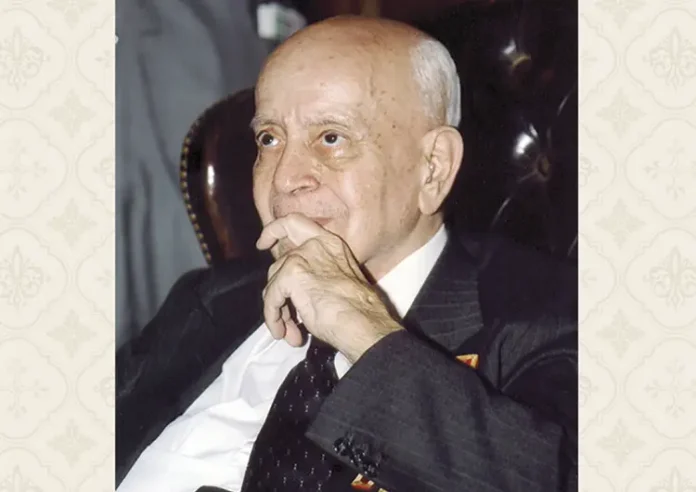

If the greatness of a man were measured solely by the volume of his works, we would already have ample reason to consider Dr. Plinio an exceptional author. His books, articles, interviews, manifestos, conferences, and informal lectures now total an incalculable number of pages. However, to define him as a notable intellectual and professor, a brilliant columnist, or a prolific writer is to consider only the footnote of his true personality and his vision of the universe.

Dr. Plinio was never a single-issue specialist, but a tireless observer of events assisted by a special prophetic charism, as seen in the previous article. Being wherever the service of the Catholic cause required him was the continuous ideal of his life. However, he devoted his greatest efforts not to public action, but to the formation of his closest disciples, in order, among other objectives, to found a new school of thought and action.

The origin of a school of thought

It was at the end of the 1950s that Dr. Plinio clearly expressed this desire, convinced that “the most important thing was to transmit a spirit and a mentality.”1 The creation, in December 1955, of a study commission called MNF – short for manifesto2 – characterized the aims, methods, and themes specific to this school.

Among the various circumstances that led to the creation of this commission was the desire to continue the theme contained in the treatise Christendom, the Silver Key, which Dr. Plinio had begun drafting five years earlier. This book contained an unprecedented vision of the perfect relationship between the Church and the State, the supernatural and natural orders, demonstrating that all good in temporal society derives from Faith and fidelity to the precepts of the Church.

Dr. Plinio put a great deal of effort into the formation of his disciples in order to found a new school of thought and of action

Thus, he sought to condense, in what would be a major manifesto, his vision of history and, above all, the description of the sacred order that will mark society with the triumph of the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

Whether describing the highest reasons for aesthetics and the noblest purposes of art, delving into the root causes of certain social transformations, marvelling at the nature and hierarchy of Angels, or drawing from the Church’s teachings on the relationships between the three Persons of the Holy Trinity, the perfect model of human relationships3 – original explanations of great theological and philosophical richness – Dr. Plinio’s school was not given to merely abstract thinking. Historical recollections and metaphors abounded; they were clear, precise, always beautiful, grandiose, and captivating. Lofty panoramas of mystical and metaphysical contemplation became simple and accessible, following the example of the Divine Master, about whom he himself observed: “The wisdom of His parables leaves any Plato at the bottom of the sea…”4

On a trip to Rome in the 1960s, he wanted to be sure of the sound doctrine of some of his explanations and asked two of his disciples to present them to experts. These scholars affirmed that his theses were so consistent with the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas that, in order to refute them, it would first be necessary to demolish the entire Thomistic edifice. This comment surprised Dr. Plinio, as he had never had time to thoroughly examine the work of the holy Dominican. Such harmony with the doctrine of the Church could only be the result of an eminent use of the gift of wisdom, which allowed him to fly beyond the solid scholastic philosophical structure, but in the same direction pointed out by its stone towers.

Mystical graces and solid doctrine

While still a student in secondary school, during Logic classes taught by a Jesuit teacher, Plinio, by the effect of a special grace, became enchanted with the logic of St. Ignatius of Loyola, which he saw shining forth in one of his disciples. This rapture of admiration was followed by an interior experience that allowed him to see the Ignatian mentality and charism with such supreme clarity that he felt penetrated by a participation in that same spirit. This imparted to him, as a freely given benefit from God, a very keen reasoning ability that would become evident in his own life.

He sought to explain and summarize his vision of history and the universe, especially the sacral order that would mark the Reign of Mary

Later, when he was in his final year of law school, a similar phenomenon occurred when he came into contact with the works of St. Thomas, through which he discerned the mentality of the Angelic Doctor so vividly that he assimilated his method of thinking and used it for the rest of his life.5

To these mystical graces he added a great and methodical effort to check all his explanations against the teachings of the Church and the philosophy blessed by it. He defined himself as a “convinced Thomist”.6

In fact, the basis of his thinking is founded on the notion of what he called the sense of being, a reference to the innate principles of the human soul that St. Thomas and Scholasticism describe as being and synderesis. In other words, the child instinctively realizes that one cannot be and not be at the same time, and that he or she is distinct from other beings. Synderesis, in turn, is defined as a habit infused into the soul by which children, from an early age, have a notion of fundamental moral principles: among them, what is true and what is false, what is good and what is evil, what is sin and what is virtue, and they constantly tend towards the good position by the force of this innate “instinct”.

Building on these philosophical foundations, Dr. Plinio explained a whole vision of the universe based on innocence. However, he did not conceive of innocence as merely the state of soul of one who has not sinned, for example, against chastity, as an overly simplistic view might suggest, but rather as an interiorly ordered state given by God early on, before the use of reason: a set of aptitudes and impulses that enable a right judgement of things and situations and allow one to always choose what is most perfect, most elevated and most beautiful. The graces resulting from Baptism strengthen this integrity of soul, despite the evil inclinations arising from original sin.

Accordingly, it is fidelity to the truth expressed in these first judgements that constitutes the state of innocence, the wellspring of Dr. Plinio’s entire school of thought and sanctity.7

The élan and fruitfulness of innocence

The state of innocence is based primarily on the confluence of the external world – the marvellous book of creation – with interior harmony and order, through a wise and natural observation of reality, followed by rational judgement and using reading and scientific research as secondary tools. “I would never be a man who reads more than he thinks: it would be like eating more than I can digest. It is an unhealthy phenomenon… I reject that illness,”8 explained Dr. Plinio.

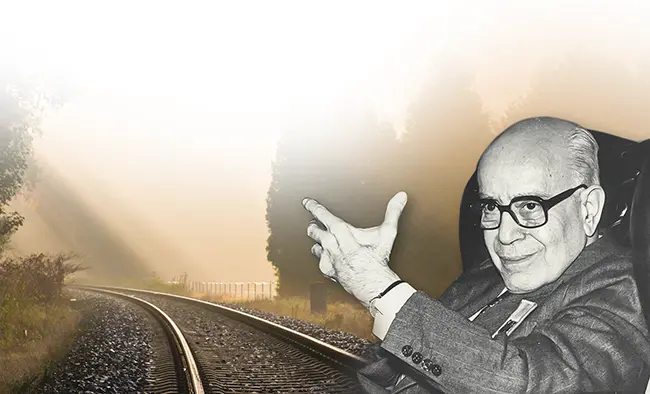

As a result of this contemplative habit, he once mentioned that he had around three hundred “railway tracks” in his mind. By this he referred to the different intuitions and unconcluded thoughts that pointed to new horizons, like the beginning of a railway line that invites one to head out into the mysteries of a distant path. He had kept some of them in his memory since childhood, convinced that he would find in each small and particular perfection a new wonder of God’s wisdom that made up the immense kaleidoscope of the order of the universe.

A brief sample of Plinian explanations

Let us mention just a few examples of themes he developed.9

Already in childhood, observing the reality of suffering in those closest to him, he understood that there were certain higher reasons for it, as well as a psychological need on the part of man to suffer, which gave rise to his explanations about the sufferative.10

At the age of eighteen, a conviction emerged in his mind, based on the teachings contained in the Book of Job (cf. 1:6-12; 2:1-6): there is a reality in which, before the divine gaze, Angels and demons wage a sustained struggle based on the merits of men, which serve as permissions for them to act on earth, either for good, the Angels, or for evil, the demons. To this zone, whose existence is based on the doctrine of the Communion of Saints, he gave the name trans-sphere, and for several years he would speak about the mysterious laws that govern it and how, in this battle, the Church is benefitted.

His ideas on symbology cover a wide range of topics in psychology and metaphysics, considering symbols not as mere conventions or analogies, but as realities linked to the world of archetypes, through which the human spirit can journey towards the Absolute, which is God.

Dr. Plinio had in his mind approximately three hundred “railway tracks”, which were unfinished thoughts pointing to new horizons

But it was the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Immaculate Heart of Mary that occupied the centre of his explanations, based on his personal experience in discerning the Soul of Our Lord. He developed sublime hypotheses about the Secret of Mary, mentioned by St. Louis Grignion de Montfort, whose revelation will enable an exchange of wills with the Redeemer and His Most Holy Mother, a phenomenon both natural and mystical, individual and collective, from which a renewal of humanity can take place.

He thus began his description of organic society on a very high level, a series of meetings in which he analyses the psychological and political-social bases of the organization of human life according to the right order of nature enlightened by grace, in which everything would be governed according to the mentality of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

At the heart of these explanations we find his global and sapiential vision of history, never presented as a simple succession of disconnected events, but understood in terms of the centrality of the Church’s mission and the enmity that began in Paradise with the “inimicitias ponam” (Gn 3:15).

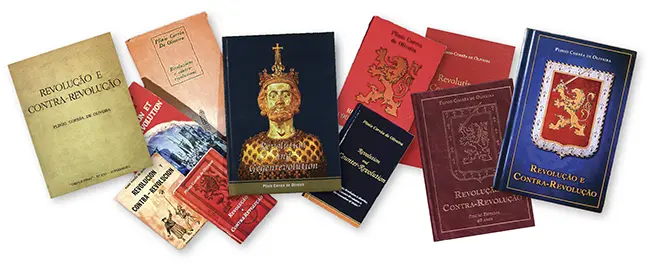

When commenting on historical episodes, he demonstrated a profound knowledge of the missions of peoples and individuals before God, pointing out the fidelities and transgressions that explained certain turning points in events, and revealing not only the immense culture of a professor, but above all a particular gift linked to the discernment of spirits. The book Revolution and Counter-Revolution, in many ways his masterpiece, is nothing less than the index of this truly prophetic vision of the Theology of History.

Universal manifesto

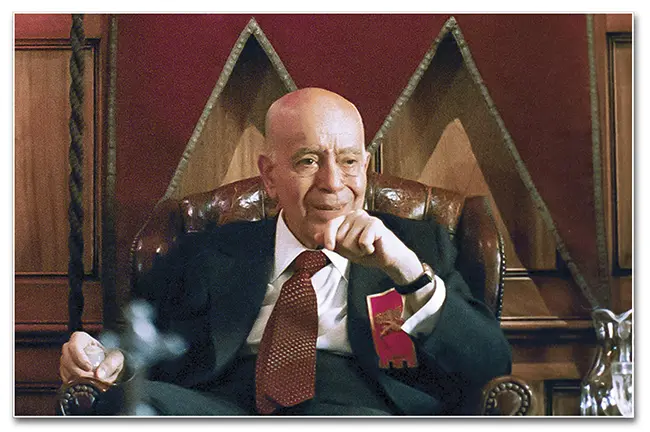

Dr. Plinio appreciated the MNF commission so much that he kept it active until the end of his life, meeting with it three times a week, despite the intense activities that absorbed his attention and the other study commissions he directed and conferences he gave. He taught, through surprising examples, that his school of thought was eminently contemplative, without, however, abandoning active life.

The MNF meetings provided the opportunity for explanations on a vast body of doctrine; but were, above all, a living and fruitful work

Although various circumstances prevented the manifesto from emerging as it had been initially conceived, the meetings allowed for the clarification of a colossal doctrinal collection, with unfathomable potentialities that will still enable the discovery of new horizons of Catholic thought in order to “revive the sense of humanity’s being, reconstituting the moral foundations corroded by the revolutionary mentality.”11

Above all, when Dr. Plinio was about to end his long earthly labours, lived without stain under the gaze of Mary Most Holy, this universal manifesto was about to be constituted, not in books to be buried in libraries, but in a living, active and fruitful work, as he ardently desired. ◊

Notes

1 CLÁ DIAS, EP, João Scognamiglio. O dom de sabedoria na mente, vida e obra de [The Gift of Wisdom in the Mind, Life and Work of] Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Città del Vaticano-São Paulo: LEV; Lumen Sapientiæ, 2016, v.III, p.515.

2 The most important details regarding this study commission can be found in: CLÁ DIAS, op. cit., p.519-561.

3 It would be impossible to provide a complete list of the topics developed by Dr. Plinio in the MNF. Only a few of them are mentioned over the course of this article. A more complete, though not exhaustive, list can be found in Msgr. João’s aforementioned work.

4 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Talk. São Paulo, 24/4/1985.

5 Cf. CLÁ DIAS, EP, João Scognamiglio. O dom de sabedoria na mente, vida e obra de [The Gift of Wisdom in the Mind, Life and Work of] Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Città del Vaticano-São Paulo: LEV; Lumen Sapientiæ, 2016, v.II, p.161-163.

6 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Autorretrato filosófico [Philosophical Self-Portrait]. In: Catolicismo. Campos dos Goytacazes. Year XLVI. No. 550 (Oct., 1996), p.29.

7 Cf. CLÁ DIAS, EP, João Scognamiglio. O dom de sabedoria na mente, vida e obra de [The Gift of Wisdom in the Mind, Life and Work of] Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Città del Vaticano-São Paulo: LEV; Lumen Sapientiæ, 2016, v.I, p.37-40.

8 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Conference. São Paulo, 18/2/1968.

9 The words in italics are part of the Plinian vocabulary or have taken on their own meaning in his explanations. They would therefore require further elaboration, but due to the brevity of this article, they will only be mentioned in passing.

10 Regarding this subject, see: RIBEIRO, EP, Leandro Cesar. Learning to Suffer. In: Heralds of the Gospel. São Paulo. Vol. 19, No. 214 (Aug., 2025), p.18-21.

11 CLÁ DIAS, op. cit., v.III, p.527.