The Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed is a joyous occasion on which the Church affords us the means to relieve the suffering souls in Purgatory. But it also holds a lesson for our own spiritual profit: we have a responsibility, and if we do not act accordingly, we may hear the terrible sentence of the Divine Judge: “You are not prepared!”

Gospel of Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed

I – A Debt Outstanding After Death

The Holy Church, in her divine wisdom and inerrancy, placed the Commemoration of All the Faithful Departed, or All Souls, in the liturgical calendar on the day after the Solemnity of All Saints. This effectively unites the three states of the Church, the Mystical Body of Our Lord Jesus Christ, of which He is the Head. Yesterday, the Church Militant—formed by those on earth in a state of trial, fighting the good fight, to afterwards receive the crown of righteousness (cf. 2 Tm 4:7-8)—celebrated the Church Triumphant, praising and glorifying the Saints that are already in eternal beatitude. Today we turn our attention to our brothers who, although they number among the just, are still in Purgatory—the Church Suffering—fulfilling the temporal punishment due to their sins.

The triple dimension of sin

Almighty God can create nothing that is not for Himself. He gave us our being so that we might practice virtue, praise Him, reverence Him and serve Him above all things. Our obligation is no other, for it was not our parents who created our immortal soul, but God alone; and we are truly born of Him. When we sin, we misuse creatures, turning our back on God and offending Him. But, in His infinite goodness, the Saviour left us the Sacrament of Baptism to expunge original sin and all actual sins committed before receiving it, for those who already have the use of reason, as well as the Sacrament of Penance to absolve the faults incurred after Baptism.1 In being forgiven by Our Lord Jesus Christ Himself, by the lips of the priest, we avoid condemnation to hell. However, besides being an offence to God, sin also rises up against two other orders—that of the conscience and of the universe—and therefore, it is logical that it be put down and punished by these orders.2

The judgement of the conscience

We all have the Law of God written on our minds and hearts, as a criterion for discerning how foolish it is to follow sinful ways. Our conscience accuses us when we act wrongly, and points out the true path. For this reason, if someone in fact commits a sin, there is no room for doubt; rather, he is sure of his fall because he acted against his own conscience.

Sin wounds the perfect order of creation

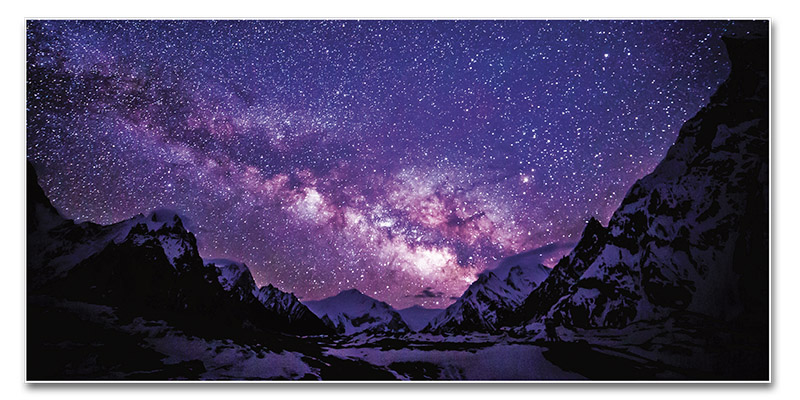

God created the universe in perfect order; each planet follows its trajectory with precision—the earth does not collide with the sun, nor does the moon leave its orbit. Vegetable life also has its laws, by which plants continually seek sun and water, while animals, in turn, have regulated instincts. Man, however, is capable of proceeding in either order or disorder. When he follows the path of virtue, he acquires merit, which cannot happen with inferior beings, such as animals or plants. But if, conversely, he embarks on evil ways, he offends the order of the universe, as the Magisterium teaches: “Every sin in fact causes a perturbation in the universal order established by God in His ineffable wisdom and infinite charity, and the destruction of immense values with respect to the sinner himself and to the human community.”3

For this reason, when someone commits a serious sin, the order of the universe, shaken, is inclined to turn against the wrongdoer and obliterate him, unleashing the elements against him. Among the possible manifestations of nature against a sinner, we can imagine, for example, the earth opening up to swallow him, or fire falling from the heavens to devour him. We find mention of this in Scripture: “For creation, serving Thee Who hast made it, exerts itself to punish the unrighteous, and in kindness relaxes on behalf of those who trust in thee” (Wis 16:24). God, however, holds nature back from annihilating the culprit in the hope that he will do penance and attain salvation.

A debt remains after Confession

Nevertheless, we should bear in mind that Baptism forgives the double penalty due to sin—the one that is eternal, in consequence of the rejection of God, and the other, temporal, due to the inordinate attachment to creatures. While Confession absolves the first, it does not, on the other hand, always totally free us from the second, because the remission of this penalty depends on the intensity and perfection of the individual soul’s contrition.4 In most cases, a debt remains to be paid, either through penance performed in this life, or in the next, when the soul will undergo the rigours of Purgatory.

In what, then, does this debt consist, and how can the soul pay it? Let us imagine someone walking down the street on a rainy day who is suddenly covered from head to toe with mud after a car speeds by. Besides washing his face he knows that he needs to wash his clothes, especially if he is on his way to a wedding, where he cannot possibly appear stained with mud.

Similarly, when the soul separates from the body and appears at its particular judgement, it receives a special gift to enlighten its memory and conscience, bringing back a clear recollection of every detail of its moral and spiritual life.5 It then realizes that, having been forgiven in Confession for its offences against God and the eternal punishment due them, its face is clean. But the conscience cries out, because it feels dirty and in need of a “change of clothes”—that is, in need of paying the temporal punishment. Moreover, the soul may still harbour mentalities that are out of line with wisdom and good order, especially in today’s world, dominated by mechanization and technology. There may also be notions, whims or fixations that deviate from the perfect balance of holiness and are contrary, as a rule of life, to the principles of Faith. As long as the soul is affected in this way, it cannot stand before God and contemplate Him face to face, because these things impede it from understanding and loving Him, and relating with Him.

Why Purgatory exists

How can we obtain pardon for temporal punishment and adjust our outlook, in order to be ready to see God? During our earthly life we can achieve this by gaining the merits associated with good works—penances, prayers, works of mercy, and the like—or by indulgences which the Church grants, “making use of its power as minister of the Redemption of Christ, […] by an authoritative intervention dispenses to the faithful suitably disposed the treasury of satisfaction which Christ and the Saints won for the remission of temporal punishment.” 6

For those who have scorned these means, Purgatory becomes necessary, to “purify [the soul] from the consequences of sin”7 post mortem, and obtain remission of its punishment, as St. Thomas says,8 paying, for a time, the debt imposed by the offense to the conscience and to the order of the universe. “It is therefore necessary,” continues the teaching of the Church “for the full remission and—as it is called—reparation of sins, not only that friendship with God be re-established by a sincere conversion of the mind and amends made for the offense against His wisdom and goodness, but also that all the personal as well as social values and those of the universal order itself, which have been diminished or destroyed by sin, be fully restored.”9

Reformatory for our egoism

God, therefore, desiring that we enter His company free of stain, pure and perfect—for “nothing unclean shall enter it, nor any one who practices abomination or falsehood” (Rv 21:27)—created Purgatory as a type of reformatory, where our egoism is burned away in fire and we are re-educated according to the true view of all things and the love of virtue. After this period, our soul is sanctified and therefore it can be said that all who are in Heaven are saints.

This is also the reason why those who attain holiness here on earth do not go to Purgatory; or, in some instances, do so only long enough to make a genuflection, for example, as is said to have happened with St. Teresa of Avila. Or with St. Severinus, Archbishop of Cologne, who, despite his life having been consumed in fruitful apostolic works for the expansion of God’s Kingdom, was obliged to remain six months in Purgatory to expiate for a lack of recollection in praying his Breviary.10

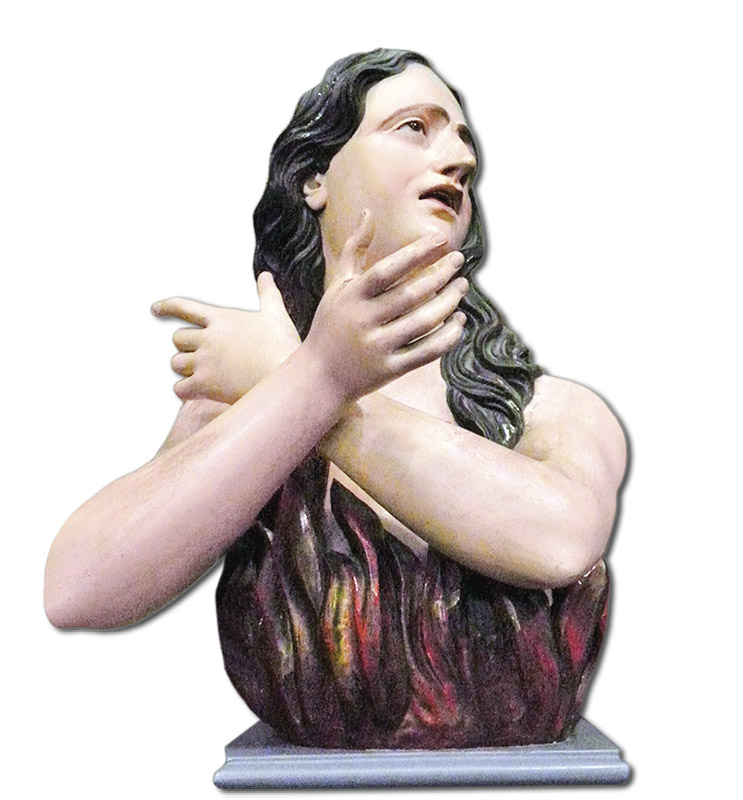

Hope amidst great torments

The souls in Purgatory suffer terribly, but with one great advantage over us: they enjoy the sure hope of Heaven. Hope is a virtue that causes joy and consolation, because it promises a future benefit. However, our hope during mortal life is doubtful and uncertain, because being here in passing, we may falter and commit a grave sin at any moment, with the risk of losing eternal life, if death follows immediately. In Purgatory, conversely, this hope is absolute, for it bears the certainty of having obtained its object; that is, of having won salvation.11

However, the torments there are dire, and while not equal to those of hell—since demons cannot torture the holy souls12 —they are fuelled by the same fire.13 To have a faint idea of the intensity of this heat, we may imagine a huge bonfire, and beside it, a painted representation of one. If we touch the painting, it will not burn us, but the moment we place our finger too close to the real fire we will experience excruciating pain. The difference between the painted and the real fire is similar to that between our earthly fire and the flames of Purgatory. According to St. Augustine: “that fire will be more violent than anything that man can suffer in this life,”14 and St. Thomas Aquinas adds: “the least pain in Purgatory surpasses the greatest suffering in this life.”15

Venerable Stanislaus Choscoca, a Polish Dominican, was at prayer one day when a soul from Purgatory appeared to him engulfed in flames. He asked him if that fire was more active and penetrating than earthly flames, and the soul exclaimed: “Compared with the fire of Purgatory, that of earth is like a light and refreshing breeze.” When Stanislaus courageously asked to feel it, the soul replied: “It is impossible for a mortal to bear such torments, but if you want a taste of it, stretch out your hand.” He did so, and the soul let a drop of searing sweat fall into his palm. Instantly, with a frightful shriek, the religious fell to the floor in a death-like swoon. After being revived by his confreres, who rushed to help him, he told them what had happened and recommended that the fact be published, to warn people of the terrible expiations of Purgatory. Finally, after a year, during which he felt continuous pain in his right hand, Brother Stanislaus died, urging his brothers to flee from sin in order to avoid the atrocious chastisements of the next life.16

The souls in Purgatory want to be purified

Notwithstanding these punishments, the souls in Purgatory are not chained there, trying to escape; rather, they fully accept their sufferings.17 Furthermore, if they knew of a thousand even more scorching Purgatories, they would want to cast themselves into them because what is most intolerable for them is to see themselves covered in stains that separate them from God. They yearn to be entirely pure and virginal to enter Heaven. This attitude evokes the ermine—the little white-coated animal that symbolizes chastity and innocence, preferring to die rather than soil its pure white coat.

II – The Church that Fights Prays for the Church that Suffers

When we minister at the bedside of someone in their final agony, we can easily have the mistaken impression—witnessing the advances of death—that the person is coming to the end of their existence. But in reality, Faith tells us that this is actually the starting point. Far from imagining that those who have passed away are disconnected from us, we should be convinced that, if they are in Heaven or Purgatory, our bond with them is much closer than we imagine. Any prayer or act having supernatural merit, including the use of holy water, practiced by the living with the intention of benefiting the souls in Purgatory, is looked upon with benevolence by God and received with great relief by the souls, since they can no longer pray for themselves. The prayers we offer for them diminish the duration of their sufferings.

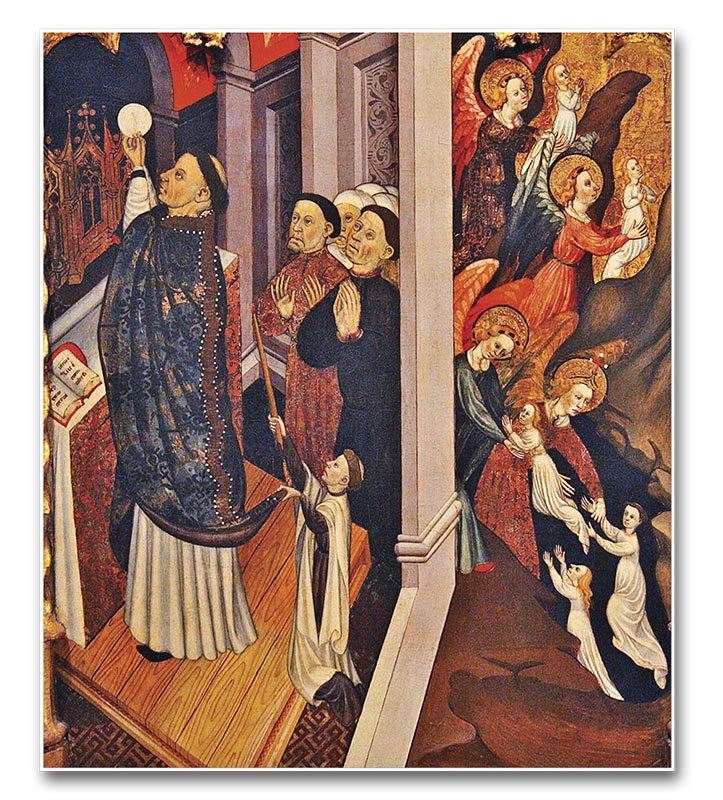

Therefore the Church, as a loving Mother, designated one day of the liturgical year for the commemoration of All Souls, in which priests are granted the right to celebrate three Masses “under the condition that one of the three be freely chosen, with the possibility of receiving an offering, and the second Mass, with no offering, be offered for all the Faithful Departed, and that the third be celebrated according to the intentions of the Supreme Pontiff.”18 This stipulation regarding the last of the three Masses springs from the zeal of the Vicar of Christ for the prompt release of the holy souls in Purgatory. Over time, many pious institutions established for the celebration of Masses for the repose of the souls of the deceased were abandoned and neglected, which signified a serious loss for the souls in Purgatory. The First World War followed, devastating Europe and claiming untold numbers of lives, especially of young men. Instituting the celebration of a third Mass on the day of All Souls, His Holiness Pope Benedict XV, with paternal generosity, took this duty of the Church toward the suffering souls upon himself.

Let us be mindful, however, that although a single Eucharist has infinite supplicatory power, the souls most devoted to the Mass during their lives will afterwards profit more from its celebration.19 Therefore, we ought to make a special effort to increase our fervour to participate in the unbloody renewal of the Holy Sacrifice of Calvary.

The Holy Church also grants the faithful the privilege of obtaining a plenary indulgence for one soul in Purgatory,20 by reciting on this day—or on a subsequent day up to November 8—one Our Father and the Creed in a church or an oratory, or by visiting a cemetery to pray for this intention.

The value of our prayers outweighs material offering

People like to place wreaths or candles at gravesites, and this is in fact a very good and legitimate practice. However, the best way to show our care for the souls is to pray for them, since the effect of prayer far outweighs material offerings, according to the famous phrase attributed to St. Augustine: “A tear for the dead evaporates, a flower on their grave wilts. But a prayer for their soul is received by God.”

We should bear in mind that God is not bound within time, and for Him there is no past or future; all events unfold before Him in a perpetual present, from all eternity and for all eternity. So, if we pray today for the good death of a relative or acquaintance—although this may have happened five or six hundred years ago—our prayer was considered by God at the moment of their passage from this life to the other, contributing to a happier death, with the assistance of efficacious and abundant graces.

A “pact” with the souls in Purgatory

This pious practice allows us to forge friendships with those who, because of our prayers, left Purgatory and were admitted into Heaven, where they acquire great power of intercession before God. It is certain that their gratitude will benefit us. If, here on earth, we are grateful to our benefactors, how much more readily will the souls entering into glory intercede for those who prayed for them?

A fitting application of the parable of the dishonest steward (cf. Lk 16:1-8) could be made here. This man, realizing that he was about to lose his position because of the mismanagement of his master’s affairs, made friends with all of his master’s debtors, so that they would open their doors to him in his hour of need, since age had robbed him of the strength to work. After his dismissal, he was supported by those whose debts he had fraudulently forgiven. While Our Lord does not praise the steward’s theft, he commends his shrewdness.

Today is our opportunity for shrewdness! We should pray for all those in Purgatory, especially those closest to us. This act of charity will win us good friends, who will reciprocate favours received in quantity and quality, coming to our aid when we most need it.

III – We Must Avoid Purgatory at All Cost

This celebration also offers a lesson of great spiritual benefit on which we will now focus, instead of examining the entire range of readings that the Liturgy includes for this day.

The tragedy of death

No one is exempt from facing hardships and sorrows in this life. Suffering borne with Christian resignation has a purifying and corrective effect, making it a sort of eighth sacrament.21 Among our many tribulations there is one that, although tentative regarding the date, must be faced by all with absolute certainty: death. We are on this earth in passing; our ultimate goal is Heaven. However, since death is such a hard truth, it is difficult for us to keep it in mind. We would prefer to cross over into eternity without having to experience that tragic moment of the soul’s separation from the body.

To help the faithful remember this reality, St. Alphonsus Liguori recommended envisioning the corpse of a recently deceased person, and meditating on the process that follows death: how the body is eaten by worms, and how even the bones, with time, crumble into dust.22 This is what happens to the bodies of those who depart from this life. But how many have already “travelled” and have not yet reached eternal happiness, but are suffering in the fires of Purgatory! This could happen to any one of us today, tomorrow or later: a loss of strength, the last breath, feeling the soul separating from the body, looking down upon one’s own body as if it belonged to someone else—inert, stiff, and growing cold… Then comes the judgement. After that, where will we go? We do not know. It is impossible, during this life, to know whether or not we will go to Purgatory…

The seriousness of Purgatory

We should not think that, for having practiced one or another good deed during our lives that when we face our own particular judgement we may escape Purgatory by giving the Judge—Our Lord Jesus Christ Himself!—a smile that will soften Him into forgetting all our faults and admitting us into glory… This is not what He affirmed in the Gospel or what is recorded in Sacred Scripture, where, in the Book of Wisdom, for example, we find many comparisons between the death of the righteous and of the ungodly (cf. Wis 3:1-19; 4:16-20, 5:14-15).

Therefore, if we are convinced of our duty to pray for the souls in Purgatory, we should be even more convinced—applying the well-known adage: “charity begins at home”—that it is not enough for us to fear hell; we must also fear Purgatory. Accordingly we must first banish the idea that venial sin is of little account, and take it as seriously as God takes it. We must not only strive to maintain the state of grace, but seek holiness with vigilant perseverance, with love and with fear of the occasions of sin. If a friendship, a situation or a television program makes me slip, I must flee from it, preferring to deny myself now than to suffer in Purgatory. How much time, and amidst what tremendous torments, could the refusal of a moment of self-denial on earth cost me?

Nourishing our souls in faith, on our way to eternity, let us strive to lead a life of integrity and holiness, in order to go directly to Heaven. If, however, we do not convince ourselves of the perfection that God demands of us, when we die—God willing, in the state of grace—we will be obliged to purify ourselves in Purgatory.

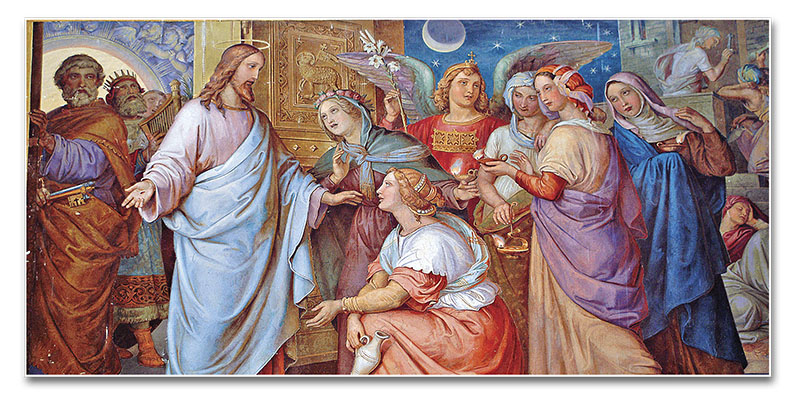

The need for vigilance

In the parable of the ten virgins—one of the Gospel options that the Liturgy proposes for this day (Mt 25:1-13)—Our Lord wants to show us the importance of being prepared for death, which comes at an unexpected hour. In those days, the highlight of a wedding feast was the bride’s entry into the bridegroom’s house. Surrounded by a group of virgin companions, she awaited the bridegroom’s arrival with his friends. Then, they would go together in solemn procession into her new home, usually after sunset, with the light of lamps and torches, with joyful singing and instrumental music. The wise virgins of the Gospel account, foreseeing a possible delay of the bridegroom, brought an extra supply of oil so as to have their lamps lit upon his arrival. The others, however, used up all their oil and their lamps were going out when the groom was announced. They pleaded, then, with the former for a little of their oil, but the wise virgins, fearing that their supply would not suffice for all of them, declined to share it with their companions. This is an image of death, in face of which each person will need his own “supply” of merits and cannot rely on others. Before God, we have a personal and non-transferable responsibility, for which we alone will be accountable. If we do not act as we should, we may hear the dreadful sentence of the Judge: “I do not know you” (Mt 25:12). And if we ask Him the reason for these harsh words, He may answer us: “Because you did not live according to My principles, My mentality and My commandments.”

The same message comes to us in another Gospel selection for this commemoration (Lk 12:35-40): the parable of the servants who await their master’s return. Jesus begins this story with a counsel: “Gird your loins and light your lamps” (Lk 12:35). The expression “girded loins” is synonymous with readiness for service, since, at that time, those people fastened their long robes with sashes, to facilitate walking, and serving tables. For us, it means being ready to practice the virtue of charity. As for having our “lamps lit,” this signifies, once again, the importance of keeping our attention attuned and alert to avoid near occasions of sin, and to maintain a spirit of prayer. We must be like the wise virgins, or like these men awaiting their master’s return from a wedding, their lamps filled with oil—that is, vigilant, shunning everything that might lead us to Purgatory. “You also must be prepared, for at an hour you do not expect, the Son of Man will come”(Lk 12:40).

IV – Maintaining Hope at the Same Time

We should not view death from a strictly tragic viewpoint, as if it were a calamity for which there is no solution, but, rather, in line with the Church’s visualization—as a necessity. Like a seed that, according to the Apostle, “does not come to life unless it dies” (1 Cor 15:36), it is necessary, at a certain point, for the body to come to rest, in the hope of the resurrection. If Jesus Himself had not died, what would become of us?

The effects of the Redemption

St. Paul, perhaps after receiving a revelation from Our Lord, wrote: “all creation has been groaning in travail together until now” (Rom 8:22) to be “set free from its bondage to decay” (Rom 8:21), through the benefits of the Passion and Death of Our Lord Jesus Christ. In fact, nature was stained by Adam’s sin and had not yet gained full access to the effects of Redemption, because these are being withheld until the Final Judgement. Theologians, particularly St. Thomas Aquinas,23 comment that on Judgement Day, after the resurrection of the body, God will open His hands and all of nature will rejoice in the fruits of the Redemption. For example, the moon will shine more brightly than before original sin, and the sun will acquire greater brilliance, imparting a wonderful radiance to the earth. Since the human creature is a microcosm, the deeper reason behind this restoration is the gathering together of all levels of creation in Jesus as Man, as a true synopsis of the universe, elevated, in Him, to the highest degree. It is necessary that the matter which He assumed in His Incarnation be glorified.

Hope in the resurrection

If nature is groaning until this day, how can we not groan as well? For although we already enjoy, through the Sacraments, a portion of the effects of Redemption, which is supernatural life—”the first fruits of the Spirit” (Rom 8:23a) spoken of by the Apostle—we are still waiting for “adoption as sons, the redemption of our bodies” (Rom 8:23b). As pilgrims in this valley of tears, far from our true homeland, we are constantly beset by temptation, trials, and anguish, and often ask ourselves, “When will we depart?” We know that, just like our soul, our body was formed by God to last forever, free from the burdens of disease, fatigue, hunger, and other limitations that our present state entails, as prayed in the Preface for the Dead: “that those saddened by the certainty of dying might be consoled by the promise of immortality to come.” 24

In one of the numerous readings that may be chosen for this celebration, St. Paul uses a realistic image, comparing the body to a tent (cf. 2 Cor 5:1, 6-10), like those he had to make to gain his livelihood (cf. Acts 18:3). He urges us not to worry if this tent is destroyed, for God will give us a much better dwelling (cf. 2 Cor 5:1). As the tireless apostle of the Resurrection, he also writes in his First Letter to the Corinthians: “What is sown is perishable, what is raised is imperishable. It is sown in dishonour, it is raised in glory. It is sown in weakness; it is raised in power. It is sown a physical body; it is raised a spiritual body” (1 Cor 15:42-44).

Indeed, the glorious body will have four gifts, namely: clarity, impassibility, agility, and subtlety.25 It is permissible for us to conjecture that, thanks to these qualities, the body will be able to make itself invisible at will, pass through solid substances, go where it wishes at the speed of thought… Moreover, we will not need the services of a tailor to clothe ourselves, for our garments will be fashioned by our own imagination, which will be perfectly balanced, without the madness that stems from sin.

The hope of recovering our bodies should enrich our existence, strengthening us to abandon fleeting and illicit pleasure, to avoid sin and practice virtue, for we will thus be highly rewarded on the day of the resurrection of the body. Then we will witness, with the same eyes with which we see now, the splendour of the renewed creation.

Therefore, while All Souls’ Day is marked with a note of sadness for the absence of the departed, we will pray for them with joy, if we maintain the perspective the Church presents to us: after crossing the tragic threshold of death, we shall all be reunited on the other side, in a community of extraordinary intimacy and joy, until recuperating our bodies in a state of glory, at the resurrection.

Let us ask Our Lady of a Good Death, the Saints, and the Angels to help us and obtain for us the favour of dying in the fullness of grace that was destined for us, in the fullest fulfilment of our mission and the fullest perfection of our soul and our spiritual life, so that we will never have first-hand knowledge of Purgatory. ◊

Notes