At the summit of the firmament, gleaming with particular fervour, the sun scattered its rays over the immense vastness of the desert, traversed by a solitary wayfarer, thirsty and weary. His journey, however, seemed to have finally come to an end. He had just come upon a robust and ancient monastery, whose walls seemed to have withstood the most impetuous onslaughts of men, of time, and of the sun.

Slow and heavy blows made the door tremble and soon open for the traveller. Two gazes met: that of the vigorous newcomer, of tireless, logical, and sensible character; and that of a venerable monk, vivacious, intuitive, and hopeful, whose age could only be perceived by the whiteness of his hair and beard. The visitor showed signs of wanting to enter the cloister.

In this metaphor, does the guest – that is, reason – have any role in Catholic doctrine, or is the cloister a privilege of faith?

However, dear reader, before continuing our story, I believe that knowing the names of these two characters will be beneficial to us. The pilgrim is called reason; the monk, faith. The desert is man’s life on this earth; the monastery, the Church; and the cloister, Catholic doctrine.

Moreover, it is fitting to ask ourselves two questions. Does the guest – that is, reason – have any role in Catholic doctrine, or is the cloister a privilege of faith? On the other hand, would not reason, which wanders so freely through the wilderness, be thereby condemning itself to perpetual imprisonment? Let us see.

The role of reason

Reason is the faculty by which man surpasses all other animals in excellence, since only he can know and raise questions as to the nature of things. Questions such as “who am I,” “where do I come from,” and “where am I going” are as old as humanity itself, which continually seeks to unravel the mysteries that surround it.

From this investigation originates science, a set of correct propositions methodically linked together by their causes and principles. What reason is in search of, therefore, is truth.

But what is truth? It consists, on the one hand, in the correspondence or adequation of what is in thought with reality. If, for example, on a day with a clear blue sky someone tells us that it is raining, only out of courtesy will we not call him a liar. Why? Because his thought does not correspond to reality.

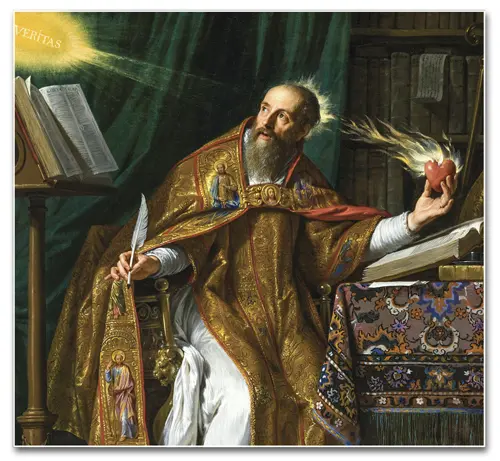

Moreover, truth has a transcendental character, since it is founded on the Word of God, who declared: “I am the way, and the truth, and the life” (Jn 14:6). All truth originates in the supreme Truth, which is God, as the Eagle of Hippo poetically confesses:

“For where I found truth, there found I my God.”1

Now, if reason is dedicated to seeking truth, its ultimate purpose can only be to reach the supreme Truth, that is, God. But is reason capable of knowing God on this earth, or will this be possible only in Heaven, where we will see Him as He is (cf. 1 Jn 3:2)?

Faith comes to the aid of reason

We have knowledge of what surrounds us through the five senses: without sight we would not know what colours are, and without touch we could not distinguish between smooth and rough. But the fact that the Almighty escapes the perception of our senses does not prevent us from knowing Him in some way: “Ever since the creation of the world His invisible nature, namely, His eternal power and deity, has been clearly perceived in the things that have been made” (Rom 1:20).

Accordingly, even if we cannot know what God is like in Himself, we can at least, by analogy with creatures, know something of His unfathomable perfection, reflected in the order of the universe. The perennity of the mountains gives us an idea of divine eternity, the immensity of the universe reflects His infinitude, the multitude of living beings indicates His superabundant generosity, and so on. Creation, therefore, postulates the existence of God as a fact proven by reason.

There are two classes of truths revealed by the Lord: some are within the reach of human reason; others exceed it, requiring the assent of faith

But if we can arrive at the knowledge of God and truth through reason alone, what is the use of faith? There are two classes of truths that the Lord has revealed to us: some are within the reach of reason – for example, the soul and its immortality, the existence of God and His perfection, the necessity of practising virtue –; others exceed it – such as the mystery of the Holy Trinity, the hypostatic union of the divine and human natures in Our Lord Jesus Christ, the world of grace, the future resurrection and angelic beings – requiring the assent of faith.

However, divine goodness has ordained that the former should also be the object of faith. Why? Because, due to their sublimity, few men would be able to reach them through mere reason.

How could those who struggle to earn their bread from the earth and are occupied with a thousand tasks find time to take a course in Philosophy? Moreover, men would easily be influenced by false arguments, which would lead them astray from the truth, were it not already established by faith. Finally, not everyone would be willing to embark on such an investigation, since laziness and disordered passions are not foreign to human nature. Hence, St. Thomas concludes that “If the only way open to us for the knowledge of God were solely that of the reason, the human race would remain in the blackest shadows of ignorance.”2

Besides these truths attainable through the effort of reason, the Creator has also revealed to us, as we have said, others that escape our understanding. The Almighty did this so that we might distance ourselves from presumption, the mother of error. In fact, many people judge as true only what they see, and despise as fantasy everything that they do not grasp through the senses.

Thus, “So that the human mind, therefore, might be freed from this presumption and come to a humble inquiry after truth, it was necessary,” explains the Angelic Doctor, “that some things should be proposed to man by God that would completely surpass his intellect.”3

One last consideration is necessary: since the certainty conferred by faith is fully founded on divine authority, its testimony should receive far more credence from us than the claims of reason, even if the latter are more evident to us. Due to the weakness of our intelligence caused by original sin, we often make erroneous and inaccurate judgments, whereas God never errs nor can He deceive us. Therefore, St. Thomas Aquinas4 asserts that, without faith, we would live immersed in falsehood.

Reason comes to the aid of faith

Reason grounds certain preambles of faith, while aiding us in understanding its truths more deeply and in defending them when they are attacked

We have just stated that faith is based on divine authority. But is not this a conclusion dictated by faith? Are we not we falling into a vicious circle here? Paradoxically, the notion of God’s authority and infallibility is given to us by reason itself. Reason proves to us, as we have seen, that God exists and, immediately afterwards, demonstrates that He does not lie. In short, reason grounds certain preambles of faith.

Through it, man can also have a deeper understanding of the truths of faith, using analogies: material light is a shadow of the Eternal Light, the lamb recalls the Crucified One, outer space represents an outline of divine bounteousness.

Finally, reason has an apologetic function, for through it the faithful can oppose those who attack the faith, presenting the falsity of their arguments, as St. Peter advises: “Always be prepared to make a defence to any one who calls you to account for the hope that is in you” (1 Pt 3:15).

Alliance and war between faith and reason in history

The relationship between faith and reason, which we have just briefly outlined, has always been the subject of heated discussions throughout the centuries. We could summarize the positions adopted in four categories.

The first encompasses all those who tenaciously neglected the role of faith. Although such people can be identified throughout history, it is worth considering that their number multiplied overwhelmingly from the 16th century onwards, especially with the advent of Modern Philosophy and Humanism.

Since then, man has come to occupy the centre of philosophical and scientific investigation, and various thinkers have endeavoured to restrict the limits of human knowledge, as well as its conditions. Thus, “reason, rather than voicing the human orientation towards truth, has wilted under the weight of so much knowledge and little by little has lost the capacity to lift its gaze to the heights, not daring to rise to the truth of being,”5 as Pope John Paul II stated. From there would arise all forms of agnosticism and relativism into which humanity is increasingly sinking. With faith, which acts as an aid to reason, disregarded, man immediately finds himself delivered to the vicissitudes of the world, like a ship that, without a lighthouse, is destined for shipwreck.

Secondly, there are those who have denied any credit to reason. Rushing into radical fideism, they dared to affirm: “I believe because it is absurd.” Tertullian was undoubtedly one of the main exponents of this thesis, which was erroneously based on the authority of St. Paul: “See to it that no one makes a prey of you by philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the universe, and not according to Christ” (Col 2:8).

Nevertheless, it is clear that the Apostle, in thus warning the Colossians, was not censuring the role of reason, but rather certain esoteric and Gnostic speculations, in which blessedness was promised only through the knowledge of certain truths, reserved for a select few.

In the third group are those who imposed a distance between faith and reason. The disciples of the Arabian philosopher Averroes are especially noteworthy. Fearing to accept the supremacy of philosophical science over faith – as their master had done – they preferred to opt for the theory of “double truth.” According to them, faith and reason deal with different truths, disparate from each other. That is, they admitted the possibility of contradiction between them. Faith could, for example, proclaim human freedom and reason could contest it, affirming that free will disappears under the blows of fate.

Finally, the fourth group includes those who safeguarded the harmony between the two. They defended the principle that there can be no conflict between faith and reason, since both are nothing but two channels that lead to the same source: truth. Hence, John Paul II began his encyclical on the subject with these words: “Faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth.”6

This proposal was widely disseminated among the Church Fathers, especially by St. Justin, Clement of Alexandria, and St. Augustine. In addition to these, there were distinguished doctors of Scholasticism who followed the same path: among others, St. Anselm and, above all, St. Thomas Aquinas.

The contribution of these champions of the Church would be summarized in the maxims: “I believe in order to understand” and “I understand in order to believe.” Their main conclusions we have already transcribed above when indicating the aid of faith to reason and vice versa.

A sacred partnership

Having outlined in swift strokes the relationship between faith and reason, the questions from the beginning of the article still stand.

Regarding the first – whether reason has any role in Catholic doctrine – the answer is certainly affirmative: faith, solitary in its cloister, not only can admit the entry of reason, but must receive it; if this were not the case, it would perish for lack of defence, preambles, and development.

And the second question? Is reason not trapped in its enclosure? Quite the contrary: it is through Revelation that infinite spaces for speculation are opened to it.

Whoever cultivates the union between faith and reason will see everything both in its concrete, palpable reality, and in its most sublime and supernatural form

After all, from the chaste nuptials between faith and reason proceeds wisdom, which is nothing other than a participation in the very knowledge of God. He who cultivates this union within himself will tend to see everything at once in its concrete and palpable reality, without dreams or fantasies, and in its most sublime and supernatural form, with an almost irresistible élan for the highest considerations.

Therefore, dear reader, if you aspire to reach that state of mind fit for strength and gentleness, for tranquillity and the unexpected, for joy and sadness, for eloquence and silence, in a word, for all ordered opposites, without ever losing the fundamental axis, which is wisdom, always preserve this sacred partnership.

Enlightened reason at the service of faith will ensure that “we may no longer be children, tossed to and fro and carried about with every wind of doctrine, by the cunning of men, by their craftiness in deceitful wiles” (Eph 4:14). ◊

Notes

1 ST. AUGUSTINE. Confessions. L.X, c.24, n.35.

2 ST. THOMAS AQUINAS. Summa contra gentiles. L.I, c.4.

3 Idem, c.5.

4 Cf. ST. THOMAS AQUINAS. Super De Trinitate, q.3, a.1.

5 ST. JOHN PAUL II. Fides et ratio, n.5.

6 Idem, n.1.