Following the development of institutions or customs has always been an effective and beneficial way of growing in love for them. Pragmatism, however – the great ruler of our age – has accustomed us to seeing things only as they appear to our eyes, focussing on their immediate usefulness and forgetting the often immense values behind them. One of the most illustrative examples of this is books.

There are thousands of books. They are sold, read and forgotten about… They usually end up in the dusty recesses of a library or, with some good fortune, on a collector’s shelf. But how much effort went into producing each one! And this reality, which applies to both old and new publications, the famous or the little-known, applies, above all, to the Work of works, the Book written and inspired by God Himself: Sacred Scripture.

Learning the journey of the Sacred Scriptures, the Book whose author is God Himself, makes us look at its pages in a different light

Today, anyone who wants to own a Bible can buy one for an often negligible sum. They come large and small, illustrated, bilingual… in short, there is a Bible for every taste. But if, while leafing through its pages, we go back to its Author and to His “scribes”, who worked since ancient times to transmit the wonders of the Lord to posterity, we will realize how many difficulties had to be overcome for the numerous copies we have today to have taken their current configuration.

Indeed, a quick overview of this book’s marvellous history will certainly make us look at its pages in a different light.

From “rule” to “rule of life”

In order to understand this intricate story, our readers will need to familiarize themselves with some specialized terms throughout the article. The first of these is canon, because the books of the Bible are catalogued in the so-called canon of Sacred Scripture.

The word has Semitic roots, although we inherited it from the Greeks: κανον, kanōn came from the Hebrew word qaneh, which in time immemorial designated a reed used for measuring, as mentioned by the prophet Ezekiel (cf. Ez 40:3-5), but which, in a derivative sense, was applied to everything that was measured or regulated.

Ancient Greek grammarians designated as κανον collections of classical works that could serve as literary models, and in profane Greek the term also acquired the meaning of norm or moral rule, with some even applying it metaphorically to those who set themselves as examples of conduct. At some point in history the Greek word was transliterated into Latin, giving rise to the word canon.1

In Sacred Scripture, the pioneer to use the term in the sense of a moral rule was probably St. Paul. The Apostle to the Gentiles employed it in his letters, writing, for example, to the Galatians: “Peace and mercy be upon all who walk by this rule, upon the Israel of God” (6:16). From then on, the Pauline epistles certainly became rules of life for Christians, but it would be centuries before they would become an official part of the biblical canon…

But let us not get ahead of ourselves. We will now return to the Old Testament.

The beginning of the divergence between Christians and Jews

Several pre-Messianic books accepted in the Old Testament canon were excluded by the Jewish people between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD

The pre-Messianic books, written at God’s command and compiled with admirable zeal by the Chosen People, constituted the first source of inspiration for the Christians of the communities born from Calvary.2 The Divine Master had given eminent proof of scriptural knowledge and His Apostles would continue to pray with the Psalms, meditating on the divine precepts entrusted to Moses and verifying the fulfilment of all the prophecies with the Pentateuch and other sacred works. All these books were accepted as the canon of the Old Testament since the middle of the first century.

However, if the reader wants to compare our Old Testament with current Jewish scripture, he will find several differences… Why?

The explanation lies between the end of the first century and the beginning of the second century of the Christian era. A great gulf already separated the old Synagogue from the nascent Catholic Church when, gathered in Jamnia, eminent rabbis, Pharisees and priests of the Jewish people defined which books they would accept as sacred and which they would not. In the end, of the numerous writings in circulation, they approved only twenty-three, and eliminated, among others, the Book of Sirach, Wisdom, Baruch, Judith, Tobit, the two Books of the Maccabees – the latter because their protagonists were not politically aligned with them – and the Greek passages of Esther and Daniel – since this language was considered pagan.3

Other books, however, had already mysteriously disappeared even before this decision by the Jewish assembly. This is the case, for example, with the Book of Jasher or the Just, mentioned in Joshua (10:13) and in the Second Book of Samuel (1:18); the Book of the Wars of the Lord, which appears in Numbers (21:14); the Book of Jeremiah against all the wickedness of Babylon, mentioned in Jeremiah (51:60) and many others… What became of these writings? What did they say? Perhaps we will never know. What is certain is that the canon of the Old Testament held by Christians became different from that defended by the Jews, just as Judaism and the Christian religion would forever be different.

The New Testament emerges

While this was happening, the canon of the New Testament was being born.

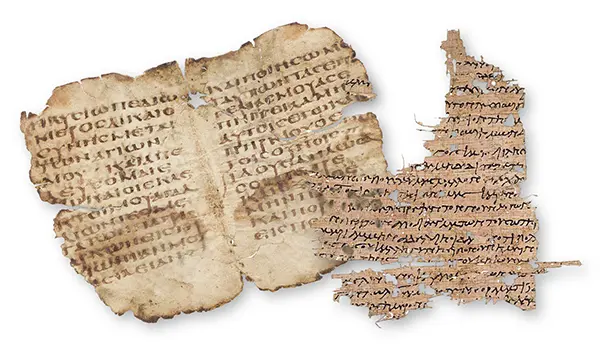

The Gospels were written until the end of the first century, as were the Acts of the Apostles, Revelation and the Epistles of Peter, James, John, Paul and Jude. These missives, addressed to specific recipients but disseminated by the nascent communities in an organic way, were included into what we know today as the New Testament.

However, do not think that the process was simple. There were heated discussions about the veracity of some writings, translations that rendered certain passages obscure, inexplicable mutilations, epistles that were lost forever and even falsified passages with the aim of diverting the faithful from the true faith or of further “embellishing” the story of the Divine Master and His Apostles – of itself already unsurpassable…

As far as the brevity of this article allows, we will consider some of the details of this process.

Disagreements among Christians

Over the centuries, controversies concerning the biblical canon have united and separated supporters of different theories, who have fought to prove their positions in a veritable “minefield” on which not even the saints have been exempt from error.

The starting point for the disagreements was translation.4 While some – following the rabbinical school – accepted only the texts written in Hebrew or Aramaic, the majority of the communities defended the Version of the Seventy, written in Greek. The first group included illustrious names: St. Jerome, Origen and Rufinus. However, the champions of the Greek version were not far behind: among them were St. Augustine, St. Irenaeus and Tertullian. On neutral ground, but with some still very imprecise conceptions, there were some like St. Athanasius, St. Cyril of Jerusalem, St. Gregory Nazianzen and St. Epiphanius.

To define the biblical canon, it was necessary to face polemics and combat heretics, distinguishing revealed text from apocryphal writings

To further cloud the picture, heretics and gnostics of all kinds also appeared on the scene, such as Marcion who, denying the divine origin of the Old Testament, accepted only the Gospel of St. Luke – full of erasures! – and some of St. Paul’s epistles. There was also Montanus who, claiming to be a “prophet” of the New Testament, tried to introduce his own “prophecies” into the biblical canon of the Bible.5

Crowning this uproar, apocryphal books – from the Greek word απόκρυφος, apokryphos, hidden – began to proliferate everywhere, a term which initially referred to “hidden writings” and was later also applied to various biblical texts which, presented as inspired, were in reality the work of forgers, some even pious, others often heretical. The multiplication of these compositions contributed greatly to spreading doubt among the faithful, who were unable to distinguish the false from the true.

It was therefore necessary for the Magisterium of the Church to make an official pronouncement in order to clarify which texts were in fact revealed and which were spurious.

The Church’s wise intervention

For this delicate selection procedure, the Holy Church needed to discern the voice of the Lord in the writings of men. “Biblical inspiration is a supernatural action of God, at once discreet and profound, which fully respects the personality of the human authors – for God does not maim the man He Himself made – but elevates him above himself, since He is capable of doing so. Thus, the books arising from the activity of these authors are not just human, but divine; they do not only express a human thought, but God’s thought. And yet they are rooted in human nature: in them everything is man’s and everything is God’s.”6

In analysing the various texts, three criteria were used, which can be identified as external, internal and ecclesial.

External criteria include the need for the text to come from apostolic times, to be orthodox – both ecclesiastically and doctrinally, to have agreement and unity in its message, and be instructive for the community.

The ecclesial criteria entail that the writing is accepted by many ancient particular churches, and that the official ecclesiastical authorities have recognized and cited it as Scripture. The role of Tradition was therefore vital in this sense: “Sacred Scripture is the word of God inasmuch as it is consigned to writing under the inspiration of the divine Spirit, while sacred Tradition takes the word of God entrusted by Christ the Lord and the Holy Spirit to the Apostles, and hands it on to their successors in its full purity, so that led by the light of the Spirit of truth, they may in proclaiming it preserve this word of God faithfully, explain it, and make it more widely known.”7

The internal criteria are the most important, as they aim to recognize the inspiration of the text. Only the Holy Church has the authority to pass judgement on this characteristic, since only she can infallibly discern when a book has indeed been inspired by the Holy Spirit.

Thus, as the Mother and Teacher of truth, the Church began to allay the quarrels and show the way forward. From the fourth century onwards, the word canon, both in the sense of a collection of biblical books recognized by the Magisterium and as a rule of faith, came into use in the Latin Church. It is known, in fact, that a document from the local council of Laodicea, held around the year 360, used the adjective canonical for the first time, referring to the Holy Books.8 Later, the dogmatic definition of the current canon of Scripture was promulgated in the decree De Canonicis Scripturas of the Council of Trent, which states that it is Catholic faith that all the books listed are sacred, inspired and canonical.9

Since then, the canonical books can be categorized as protocanonical and deuterocanonical, continuing our list of little-used words. The Greek particle πρώτο, proto means first; and δεύτερο, deutero, in turn, second. Protocanonicals are therefore the first books to be canonically acknowledged, those which, in both the Old Testament and the New, have always been considered revealed; and deuterocanonicals are the books accepted later, after centuries of discussion regarding their divine inspiration. The New Testament deuterocanonicals include the Letter to the Hebrews, the Letter of St. James and St. Jude, the Second Letter of St. Peter, the Second and Third Letters of St. John and the Book of Revelation.

Thus it came down to us

It is amazing to think of how many controversies took place in the first centuries of Christianity! Thereafter, the Bible still had to face the whims of the Renaissance and the Reformation, the clashes against the adulterated translations of Luther, Zwingli and Calvin, the contentions of modern researchers, the revealing clarifications of science… in short, a veritable odyssey.

The Church as Teacher of the truth showed the way, and we thus received the treasure of Sacred Scripture, apostolic legacy and bulwark of our Faith

In spite of everything, the decisions of Trent endured and were reiterated in various subsequent magisterial documents, such as the Dogmatic Constitution Dei Filius of the First Vatican Council, the Encyclical Providentissimus Deus of Leo XIII and the Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation Dei Verbum of the Second Vatican Council, which brought the centuries of discussion to a close.

This is how we received the treasure of Sacred Scripture, the apostolic legacy and bulwark of our Faith, the Book written by God to illuminate human history! ◊

Notes

1 Cf. PAUL, André. La inspiración y el canon de las Escrituras. Navarra: Verbo Divino, 1985, p.45-47.

2 Since ancient times, the Jews separated their sacred writings into three groups: the Torah, meaning law, comprised the Pentateuch; the Nevi’im, prophets, brought together the prophetic books; and the Ketuvim, meaning writings, grouped together the rest of the works.

3 Despite this, reminiscences of these writings and references to them are found in the Jewish midrash.

4 Cf. ARTOLA, Antonio M.; CARO, José Manuel Sánchez. Biblia y Palabra de Dios. Navarra: Verbo Divino, 1989, p.90-100.

5 Cf. BARUCQ, A.; CAZELLES, H. Los libros inspirados. In: ROBERT, A.; FEUILLET, A. (Dir.). Introducción a la Biblia. 2.ed. Barcelona: Herder, 1967, v.I, p.69-70.

6 Idem, p.36.

7 SECOND VATICAN COUNCIL. Dei Verbum, n.9.

8 Cf. ARTOLA, op. cit., p.64.

9 Cf. DH 1501-1505.