In the gardens of the Academy, comfortably seated and reflective, master and disciple still seem to be meditating: Socrates, his chin supported in his hand, prepares to bring into the world yet another concept; at his side, Plato, with an attentive ear, waits patiently. However, tourists come and go, days pass, and the wise men utter nothing new: the stone from which they were carved is incapable of this; they are mere statues, impassive to the centuries and to the elements.

Many are those who, like them, entered history through the portico of human wisdom, borne by a brilliant intelligence or an unusual talent, and had their memory immortalized in books and monuments.

Perhaps Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira’s name could be added to this list of illustrious figures… As was amply demonstrated in a previous article, his natural ability lent itself to this, which was evident to those who knew him closely. One day, in fact, a certain bishop who was very close to him advised him to withdraw from his absorbing apostolic labours and the direction of souls in order to devote himself exclusively to writing, so as to leave his thoughts duly recorded. “We will die,” the bishop concluded, “but books live on through the centuries.”

Undoubtedly, thinkers enrich philosophy and science, inspiring schools and filling libraries, and in this sense that prelate was right. However, there is something that all of these lack: the memory of their works is everlasting, but lifeless, like the sculptures of Socrates and Plato in historic Athens… With them, their genius dies; what remains for consultation are the inanimate writings that constitute their entire legacy, often consigned to the dust of oblivion.

However, Dr. Plinio’s great mission was not limited to the craft of the sage as the world conceives it (cf. 1 Cor 3:19-20). Providence had adorned his soul with superior knowledge: his wisdom was of a supernatural order, and it far transcended the services of earthly understanding. Elevated to the category of a gift of the Holy Spirit, it enabled him to grasp all realities – of God and of creatures – from a divine vantage point, and to arrange everything according to this privileged vision.

Thus, Dr. Plinio would perpetuate the immense treasures born of his contemplation of the order of the universe not only in papers and brochures, but would also transmit them to his disciples. These, above all, he would invite to follow him further, in imitation of his ways and in a communion of objectives.

Indeed, Dr. Plinio’s greatest concern throughout his life was not his public action or his intellectual production, although both were fruitful facets of his existence, but rather his commitment to gathering a handful of followers willing to adhere unconditionally to the good. Anointing their souls with his prophetism, Dr. Plinio would be a father to them, and they would be his children.

First attempts

At the dawn of his battle, when he had just completed his first decade of life, his selfless and generous attitude towards others stood out. When confronted with the Revolution in the school environment and discerning the evil it contained, he did not choose to shut himself off in the serenity of his innocence and rest on his own righteousness, but decided to help his companions and prevent them from being unconsciously or weakly swept away by the worldly waves. Thus, along with the counter-revolutionary epic that would span his life, his apostolate was also born.

While still a young university student and Catholic leader, he saw the first fruits of his zeal blossom: small groups of followers gathered around him. How blessed these early combatants would have been if, open to Dr. Plinio’s prophetic vision and fidelity, they had fully responded to this gift, allowing themselves to be led by him against all odds!

But, alas, shaken by the cruel persecution – sometimes overt, sometimes silent – that was unleashed upon their master, some betrayed him, others blamed him for the failures that transpired; in the end, all of them turned to trivialities, making them the object of internal dissensions that Dr. Plinio was forced to resolve, exhausting much of the energy that he could have applied to combats that in his eyes were much more glorious …

However, amid denials and uncertainties, the delicate action of Providence would gradually reveal his lofty mission. His work with these companions would transcend the limits of a mere Catholic public figure and take on their true proportions.

Union with the Counter-Revolution

Although he foresaw a great future awaiting him, Dr. Plinio wondered, in his humility, if there was someone he should follow. Like a vassal in search of his lord, he visited eminent ultramontane figures in the Old Continent, but their inconsistent moral conduct and nostalgic position, lacking in initiative, extinguished his last hopes…

From this painful realization blossomed the certainty of the exceptional calling with which he had been graced: “I realized that an almost millennial tradition was expiring, but it did not die entirely because it lived in me, and from me it would have its rebirth. There was a kind of union between this vocation and myself that was much deeper than before; a true exchange of will with the Counter-Revolution, as opposed to all the evil done and bringing with it the seeds to destroy that evil and do the opposite, by which I became co-identical with it.”1

Dr. Plinio’s soul, like a treasure chest where the sublimities of the past and the promise of future splendours coexisted, was ready to bring forth the sons and daughters who, over the decades and centuries, would become the heirs of his spirit and his struggle. Perhaps the suffering caused by the isolation and incomprehension he faced was the precious ransom he paid to Our Lady for the new generations.

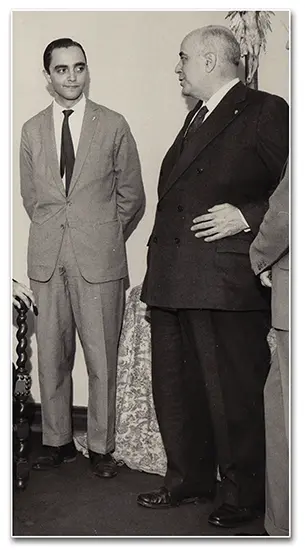

Dr. Plinio with Msgr. João in the mid-1960s

Indeed, after years of sterility and turmoil, as if by miracle, the Group2 took on a new life with the young people who have been arriving ever since. Among them, without a doubt, the most blessed fruit of Dr. Plinio’s spiritual fertility was Msgr. João, future founder of the Heralds of the Gospel.

Paternal reception for a broken generation

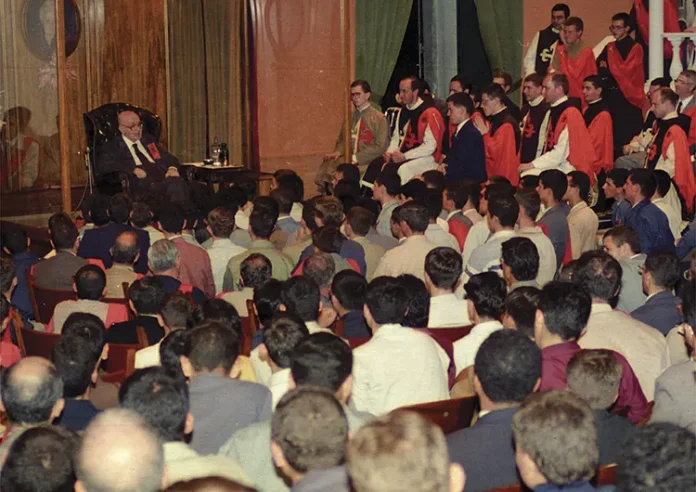

Perhaps a contemporary observer would be amazed if he were given the opportunity to contemplate the moments of conviviality between Dr. Plinio and his younger disciples. Although absorbed by tasks of great importance in defence of the Catholic cause and Christian civilization, he never lacked time to advise one, encourage another and talk to all, in a relationship that harmonized seriousness and benevolence, respect and intimacy.

With the first members of that generation, not yet ready to participate in the conferences given to the members at large, he took advantage of a brief commentary on the saint commemorated on that day to impart to them a wide variety of teachings. These informal talks took on such importance that, over the years, they became one of the cornerstones of the formation given by Dr. Plinio and took the place of the plenary meetings, far transcending their initial content.

The growth of the work brought Dr. Plinio an increase in activities and a consequent reduction in available time. However, he did not fail to use certain periods within his busy schedule to spend time with those who were taking their first steps in the counter-revolutionary vocation.

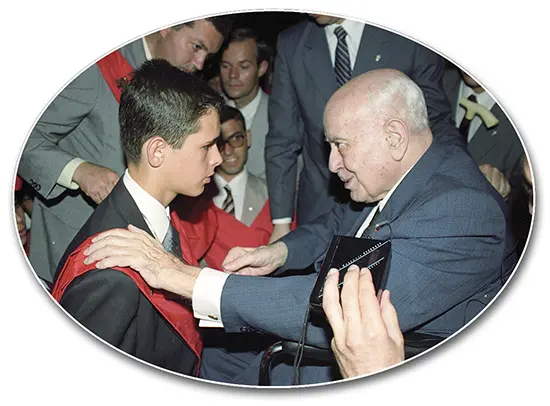

He would, for example, have short but blessed conversations, in which groups of young men – whether students before leaving for their classes or very young disciples visiting from other regions of Brazil and abroad – confidently shared their struggles in the fight for virtue at such a delicate age, their incipient doctrinal questions, or their curiosity about the story of the father who welcomed them with such kindness. Dr. Plinio attended to everyone and usually concluded the gathering by greeting each one personally, an unforgettable moment in which there was no lack of quick but profound exchanges of words and advice, illuminated by the charism of discernment of spirits with which he had been adorned by Providence.

And what about afternoon tea – part of his routine since childhood – during

which he took the opportunity, surrounded by his slightly older sons, to answer a wide variety of questions, resulting in a wealth of teachings that are still extremely useful to subsequent generations today?

These touching examples of dedication, of which we have only given a few brief glimpses, were not spontaneous manifestations of circumstantial affability. On the contrary! More than instructing minds, the Revolution had forged a way of being – sloppy, vulgar and unrestrained – by which it dragged the world along. In contrast, Dr. Plinio took advantage of every opportunity to patiently and masterfully form his disciples into living symbols of the Counter-Revolution, so that their subsequent actions would constantly invite prodigal humanity to the good, and constitute a basis for the establishment of the Reign of Mary.

Dr. Plinio greeting one of his sons on January 31, 1993

The fertile seed of a new form of community life

However, in order for them to achieve such identification with the cause, it was necessary for them to distance themselves from worldly distractions and allow themselves to be moulded by the supernatural atmosphere. Years earlier, on a trip to Europe, Dr. Plinio had observed the beneficial effect on his companions of long periods spent in prayer at the Franciscan monastery Eremo delle Carceri. Discerning in this fact a sign of Providence, some time later he would establish the so-called hermitages, residences where his disciples, leading a community life devoted to contemplation, ceremony, and intellectual work, would seek to translate the principles of the Counter-Revolution into ways of being, as Dr. Plinio explained when outlining the mission of the community that was to be the model for the others: “This is the hermitage of doctrine converted into facts, of wisdom embodied in people, in action, in lifestyle, in concrete, palpable and tangible realities. This is the engine of the ship: to present wisdom in practical, experiential terms, through which the person ascends to the doctrine.”3

However, in order to shape a human type, in addition to the environment, a specific garb was necessary: inspired by what they already wore as tertiaries of the Carmelite Order, a new habit was designed. Upon contemplating it, Dr. Plinio expressed his satisfaction: “[The scapulars] fully express the spirit that we must carry.” He concluded: “For the first time in my life, I will wear a garment in which I feel myself expressed.”4

Gregorian chant, silence, prayer, discipline: everything contributed to restore balance, peace and composure to souls marked by a revolutionary pace. Thus, little by little, Dr. Plinio introduced those young people to a life of ceremony, in which sacrality was the teacher.

“I became your father in Christ”

Dr. Plinio communicated to them the spirit of the Counter-Revolution that filled his soul, taught them to take sure steps in virtue, comforted them in their struggles, and supported them in their falls: he was, in the highest sense, a father to them. He could rightly repeat the words of the Apostle: “I became your father in Christ” (1 Cor 4:15).

The relationship established by this spiritual filiation was based on a deep affection that sprang from his paternal heart and found an echo in his followers: “My sons, something in your relationship with me […] reminds me of my relationship with my mother. […] It is a repetition of my own story, fulfilling the proverb that says that a good son makes a happy father.”5

If paternal affection is already something admirable when reciprocated, perhaps its deepest beauty is only revealed in the face of ingratitude. In a conversation, Dr. Plinio revealed: “When I see a member of the Group, even when he is wasting the remainder of the calling that is not extinct in him, I am well disposed towards him and bear him this spiritual love. This does not presuppose reciprocity. The very nature of paternal love is such that it almost eliminates reciprocity. So that, even when receiving the worst ingratitude, it acts as if nothing had happened.”6

And these were not mere words. In dealing with those associated with him, as long as there was true repentance and a desire to make amends, he was willing to overlook even the greatest infidelities, focusing his attention on the calling that Providence had placed in that person’s soul and leaving the rest behind.

Fatherhood beyond time

Having Dr. Plinio as a father was not an exclusive privilege of the generations who enjoyed the good fortune of his direct company. Governed by the laws of the spirit, his fatherhood is not subject to the limitations of nature or the dictates of time.

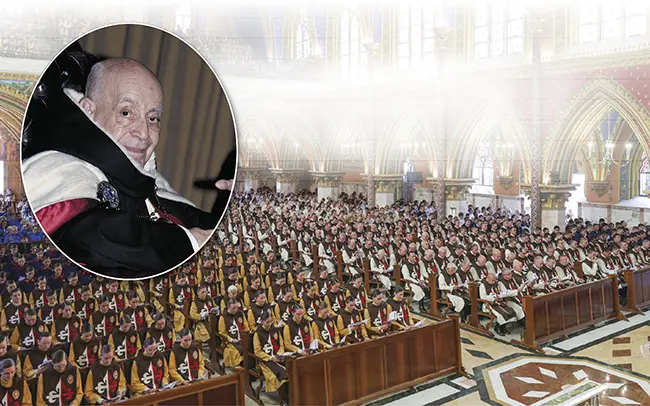

Mass at the Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary, Caieiras (Brazil); inset, Dr. Plinio on December 14, 1994

In fact, if someone were proud to belong, in the hundredth degree, to the lineage of a great personage, the laws of matter would not allow them to consider themselves directly his child, for centuries and generations would separate them. From eternity, however, Dr. Plinio continues to beget spiritual sons and daughters, to whom he transmits his spirit and leads in the ways of the Counter-Revolution.

Thus, over the years, the bond that unites us to him does not weaken or fade. Today, three decades after his passing, the same affection rises up to him from hearts that, never having met him physically, but possessing his spirit and continuing his work, can rightly call him father. ◊

Notes

1 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Talk. São Paulo, 12/12/1985.

2 The name given internally to the movement founded by Dr. Plinio.

3 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Talk. São Paulo, 6/3/1972.

4 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Talk. São Paulo, 13/9/1971.

5 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Conversation. São Paulo, 23/10/1980.

6 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Conversation. São Paulo, 4/4/1988.