Through his monks, St. Benedict converted a continent and laid the roots of a new civilization. The way of life he founded continues to be a light for our troubled world today.

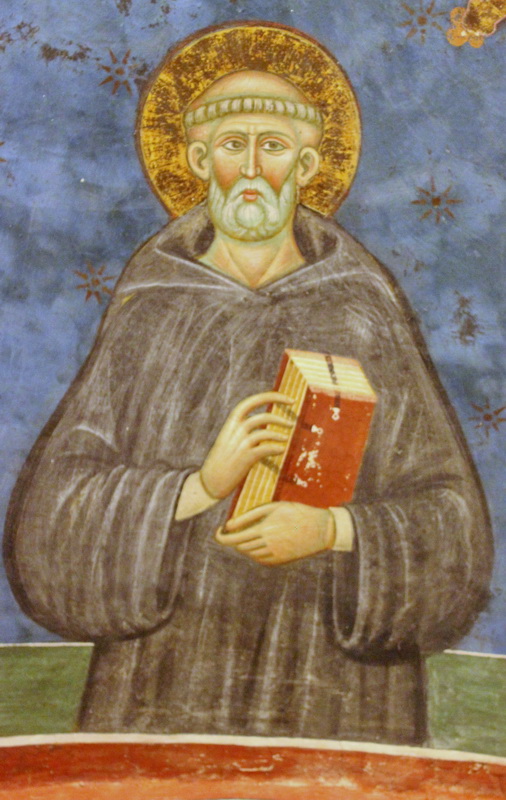

When we recall the early days of Europe’s evangelization, the figure of the great Patriarch of Western Monasticism immediately comes to mind, St. Benedict of Norcia and his monks. Amidst silence, discipline and work, prayer, study and liturgical ceremony, the Benedictine Order “had an enormous influence on the spread of Christianity across the Continent”1 and has marked 1,500 years of history.

However, at the beginning of his mission, it is likely that not even St. Benedict himself clearly understood the enormous call that Providence had reserved for him: to forge a new human type, raised up by God to renew the society of his time.

A new civilization is born from a young man’s fidelity

The young Benedict, born around 480, was sent by his family to the Eternal City to study. Nevertheless, his Christian soul was repelled by the decadent Roman society, convulsed by barbarian invasions and, above all, by the degradation of customs. Feeling the clash between those surroundings and his own integrity, he withdrew to the solitude of Mount Subiaco in order to live there as a hermit. No one could have imagined that the future of Christian Europe was about to germinate in an unknown cave, hidden from the eyes of men…

In 529, he relocated from Subiaco to Monte Cassino, initiating an experience of community life with some disciples under his direction. The very essence of the rule taught by the holy founder to the monks was to “establish a school of the Lord’s service.”2

In their evangelizing activity, the Benedictines – as his spiritual sons came to be called – spread throughout Europe, founding monasteries that marked the beginning of various nations with the sign of the Faith, including England, Germany, Austria and Sweden. And they did so using only their religious influence. By means of hymns, zeal for liturgical splendour, their excellent agricultural methods and their charity towards the poor, they marked these regions with their “ora et labora” and the good odour of their virtues.

Slowly, the voice of St. Benedict went out through all the land (cf. Ps 19:4), and he became the father of a civilization born of contemplation, of love for God, of hearing the Word – in short, of a young man’s generous “yes” to his great calling.

A sure path to God and progress

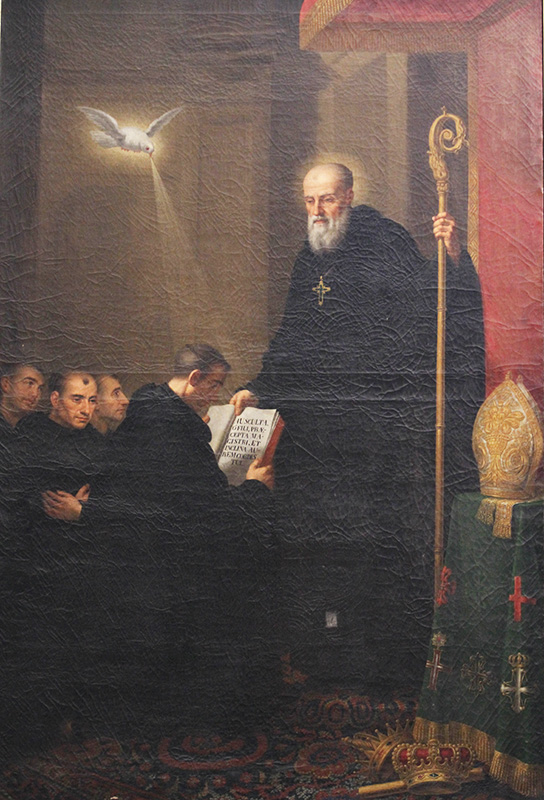

With the emergence of Cluny, the Benedictine monasteries constituted a kind of confederation of abbeys that allowed the Order’s mysticism and ideal of life to radiate further and with greater penetration. Inspired by them, the Middle Ages yielded their peak fruits in the spiritual, cultural and artistic realms.

Cluny made its presence felt in the society of that time due to “its decor (decorum) and nitor (clarity) […] that were admired especially in the beauty of the Liturgy, a privileged way for reaching God.”3

In proclaiming St. Benedict as “Foremost Patron of All of Europe,”4 Paul VI recognized the magnitude of the work which the Saint and his monks accomplished in the formation of European civilization and culture. But not only that: with this gesture, the Pontiff indicated to the modern world a sure path amid the cultural and religious transformations it was undergoing.

In the same vein, Benedict XVI warned that political, economic and social measures are not enough to overcome the problems that today afflict Europe, and, mutatis mutandis, the whole world. What is needed above all is “to awaken an ethical and spiritual renewal which draws on the Christian roots of the Continent. […] Today, in seeking true progress, let us also listen to the Rule of St Benedict as a guiding light on our journey.”5

Spreading of the fruits of Redemption

The Holy Church puts forth its utmost effort in the quest for the salvation of souls. However, as a corollary of this primordial mission, it seeks to promote every form of goodness, beauty and dignity in human life, in order to glorify God and facilitate the practice of virtue.

Something similar can be said of St. Benedict, who “at the end of Antiquity, created a style of life that led Christianity to overcome the time of barbarian invasions.”6 His lofty virtue acted as a salutary “spiritual leaven,” which propitiated the birth of Christian Europe from the ruins of the Roman Empire.

The “St. Benedict phenomenon” shows that ecclesial, monastic and religious life can influence temporal society in a remarkable, positive and holy way. This good influence is nothing other than the spreading of the fruits of Redemption to all areas of human activity. ◊

Notes

1 BENEDICT XVI. General Audience, 27/4/2005.

2 LA REGOLA DI SAN BENEDETTO [THE RULE OF ST. BENECIDT] Prologue, n.45. 4.ed. Montecassino: [s.n.], 1979, p.7.

3 BENEDICT XVI. General Audience, 14/10/2009.

4 BLESSED PAUL VI. Pacis nuntius.

5 BENEDICT XVI. General Audience, 9/4/2008.

6 RATZINGER, Joseph. La sal de la tierra. Quién es y como piensa Benedicto XVI. Una conversación con Peter Seewald. 9.ed. Madrid: Palabra, 2006, p.293.