Almost unknown to the European continent until the end of the fourth century, Ireland was profoundly Christianized after the evangelization began there by St. Patrick. The extraordinary flourishing of religious life in these lands earned it the nickname Isle of the Saints.

From the beginning of the sixth century, countless monks left Ireland to evangelize the barbarian peoples of nascent Europe. “Irish monasticism thus became a bridge between the Roman Empire and its disappearing culture, and the new world which was struggling to emerge.” 1

Among all the religious who set out from the island at that time, St. Columban stands in a category of his own as the most distinguished Irish missionary.

A youth of fine intelligence and appearance

Little information has reached us about his birth and early years. It is known that he was born in Leinster around 550, the time of the death of the patriarch St. Benedict.

From the very cradle his education and training were thorough; his parents provided him with the studies in the Holy Scriptures and the literary sciences. “He studied Grammar, Rhetoric, Geometry and other subjects best suited to form a cultured young man, according to the custom of the time and place.”2

In addition to spiritual gifts, Providence had endowed him with special grace and physical beauty, which could have been a motive for him to abandon himself to inordinate passions and sins. In fact, there was no lack of vain young women who, moved by lust, futilely endeavoured to drag him to perdition.

At the age of fifteen, repulsed by the illusions of this passing life and feeling the need to preserve himself from the world’s disorders, he sought advice from an anchoress famed in the region for her sanctity. He explained his temptations to her, and asked her to recommend a sure remedy so as not to fall into them. “Flee, […] if you wish to save yourself. For your age and circumstances, there is no caution that will suffice if you remain in the world. Do not believe that you can speak and walk with impunity in the midst of female vanities without experiencing their poison […]. Flee, my dear son; flee, if you wish to avoid falls and perhaps eternal ruin!”3

Beginning of a great vocation

The words of the venerable old woman sank deeply into Columban’s soul. He discerned this to be God’s call and fled from the world and its dangers. First he withdrew to the house of a holy man named Sinell who had a profound knowledge of sacred texts, and later went on to the monastery of Bangor, then the most renowned in Ireland.

With three thousand monks imbued with springtime monastic fervour, the monastery was illuminated by its abbot, St. Comgall, reputed for his austerity and paternal guidance of his disciples. He warmly welcomed Columban, who entered with the determination to be a true Saint. Clothed in the monastic habit, his ardent spirit found there the nourishment it craved, and he took heroic steps along the paths of renunciation and abnegation. He remained there just over ten years, during which time he was ordained a priest.

Nevertheless, he felt that other lands and other peoples were calling him, and he set his sights on Gaul. St. Comgall, seeing the divine inspiration in this desire, gave him permission to leave with twelve of his fellow disciples, in honour of the twelve Apostles.

Abundant fruits of his apostolic zeal

In a few days’ journey he landed in Gaul, the land to which he was to devote half his life. At that very time there was talk of an enormous decline in the religious spirit which had begun so well a century earlier with Clovis. This was due both to frequent enemy invasions and to the negligence of the shepherds.

In Burgundy, King Guntram offered him an old Roman castle in ruins in the middle of the forest to settle in. There he started his first foundation, Anegray, which became famous throughout the region. He spent several years within its rough walls, living a coarse and austere life, until the excessive number of disciples obliged him to start a new foundation, the monastery of Luxeuil, which in future centuries would be one of the most flourishing centres of European culture and civilization, a kind of French Monte Cassino. This was followed by the foundation of the monastery of Fontaines.

These initiatives yielded immense benefits. The forests and wasteland where the monasteries were established were cleared and cultivated. Countless regions of present-day France were urbanized by monks, who “carried out heavy work in the fields with the same perfection with which they wrote the fine parchments of their codices or strove to guide souls with their ardent words.”4

Beacon of virtue and holiness

Columban’s labours gave a strong impetus to religious and temporal life in Europe, for “it can be proven that more than fifty [monasteries] all over the continent came under the influence of the monks brought by him. On the other hand, precisely this incomparable ensemble of monasteries was in the following centuries the basis of everything that stands for civilization.”5

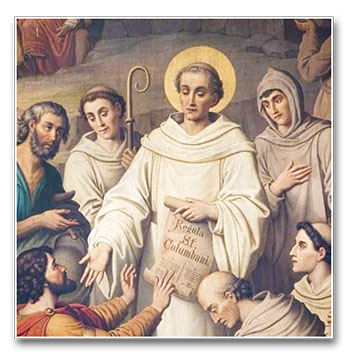

St. Columban confides the monastic rule to St. Waldebert – Abbey of Luxeuil, Luxeuil-lesBains (France)

His personal influence was equally powerful. His fiery speeches seemed to convey the voice of the Almighty to men, and on his face the power of God shone visibly. Bishops regarded him with admiration and respect, kings came from all parts to consult him and the people venerated him. When he left his monastery to visit another province, vocations sprang up in his wake.

The Lord also gave him the gift of instilling the purest and loftiest monastic spirit in the hearts of the young, and encouraging its development in an incomparable way. Parents entrusted their children to him to be educated in piety and literature, and formed in monastic discipline.

The rule and discipline, drawing souls to the monastic life

In the vigorous hands of this holy abbot not only work, but also prayer, took on proportions hitherto unknown. The multitude of monks, from both peasant and noble stock, quickly grew to six hundred, which provided the opportunity for him to institute what was known as laus perennis, a series of prayers and hymns recited continuously throughout the day, the monks raising their voices, “as indefatigable as those of the Angels,”6 in praise of God, interceding for sinners, for Christendom and for concord among kings.

In Luxeuil, where he lived for almost twenty years, the tireless abbot also composed a monastic rule – the Regula monachorum – for the foundation and buttress of the spiritual edifice he was building. With time, it became even more widespread than the Benedictine Rule.

He also left a penitentiary, De pœnitentiarum misura taxanda, by means of which he “introduced Confession and private and frequent penance on the Continent. It was known as ‘tariffed’ penance because of the proportion established between the gravity of the sin and the type of penance imposed by the confessor. These innovations roused the suspicion of local Bishops, a suspicion that became hostile when Columban had the courage to rebuke them openly for some of their practices.”7

An action that sparked enmities

Queen Brunhilda, by Mary Evans

While in Austrasia, a region straddling the borders of present-day France and Germany, he became involved in a conflict with Queen Brunhilda, grandmother of the young King Theodoric, concerning the honour of Christian morality.

The ambition to reign alone led Brunhilda astray: fearing that the monarch’s marriage with a princess would overshadow her power, she persuaded him to live with concubines. Moved by his pastoral zeal, the holy abbot convinced the king to marry legitimately, but such was the pressure of his grandmother that in less than a year Theodoric had repudiated his legitimate wife and turned to a life of adultery.

One day, while visiting the court, the monk came face to face with this unworthy woman, who presented him with Theodoric’s four illegitimate children:

“These are the king’s children; strengthen them with a blessing.”

“No,” replied Columban, “they shall never reign.”8

From that moment Brunhilda declared mortal war against him. She forbade his monks to leave the monastery or to receive help from anyone. The intrepid Irishman then proceeded to Theodoric’s palace, to enlighten him and try to bring him back to good morals. On hearing that the abbot had arrived but would not enter, the king sent him a sumptuously prepared meal in order to win him over. Columban refused to accept the food from the hands of the one who had just allowed such a severe blow to be dealt against his spiritual sons. He merely made a Sign of the Cross over the platters laden with food, and they all shattered miraculously.

Theodoric was astonished at the prodigy and came to ask pardon, promising to make amends. But he relapsed into his debauchery and, under pressure from his grandmother, brutally expelled the Saint from his territories, even threatening to violate the cloister. Columban, however, warned him with his customary audacity: “If you come here to destroy our monastery, your kingdom will be destroyed, together with all your descendants.”9

Unjust exile

Columban was taken from his community to the city of Besançon until his fate should be decided. In the meantime, the valiant warrior of Christ took the road to Luxeuil again, to be with his monks. The king, blind with rage, sent emissaries to retrieve him, if need be by force.

The men arrived when he was praying the Psalms with the community and ordered him to return to Besançon, whence he was to leave the continent. He replied that, after having forsaken his homeland for the service of Jesus Christ, he knew that God did not will his return. Faced with this manifestation of fidelity and firmness, the emissaries knelt and begged his pardon, but told him that his refusal would mean death for all of them…

In view of this injustice that would be committed against them, “the intrepid Irishman acceded and left the sanctuary that he had founded, his abode of twenty years, which he would see no more.”10 A tremor of sadness and apprehension ran through the monks and many were willing to accompany him into exile, an intention soon frustrated by the royal prohibition on leaving the monastery, applied to those who were not Irish.

Following this episode, Columban would yet traverse various regions of Gaul, performing miracles and portents. On one occasion, he reiterated the curse that the Most High had decreed against the royal family, ordering one of the guards to convey this message to Theodoric: “Tell your friend and lord that in three years he and his children will be annihilated and that his entire race will be extirpated by God.”11

Columban passed through the court of Chlothar II, king of Neustria – present-day northern France – and there predicted that one day he would reign over all the Franks.

Last years of an arduous struggle

Finally he decided to set out for Italy, fertile ground for the apostolate, where paganism and Arianism were threatening the Church’s growth. Although an Arian, the king of the Lombards, Agilulf, received him benignly. Immediately upon his arrival in Milan, Columban began to write against the perfidious heresy that held sway, chiefly among the Lombard nobility.

The king did not withdraw his friendship on that account, but gave him land in a region called Bobbio, where the abbot restored an old church dedicated to St. Peter and built his last monastery, which became an enduring stronghold of orthodoxy against the Arians and a centre of science and learning that would illuminate all of northern Italy. Its school and library, rich in codices, became one of the most famous of the Middle Ages.

During the three years he spent in Bobbio, his prophecy concerning Theodoric’s family came true. The latter died suddenly at the age of 26, Queen Brunhilda was brutally murdered, and the king’s two eldest sons were massacred. As for Chlothar II, he became, by dint of blood and iron, the sole king of all the Franks as the Saint had foretold.

The Abbey of St. Columban, Bobbio (Italy)

The end of his days

In Italy, the venerable abbot ended his days clothed in the same zeal that had set him on the road to sanctity. Seeking even greater solitude than he had in the monastery, he found a cave in Bobbio which he converted into a chapel dedicated to the Blessed Virgin. There he spent his last days in fasting and prayer, returning to the monastery only on Sundays and feast days. On November 21, 615, he left this world to dwell with God in the company of the Angels and the Saints.

In the words of Benedict XVI, “St. Columban’s message is concentrated in a firm appeal to conversion and detachment from earthly goods, with a view to the eternal inheritance. […] He was a tireless builder of monasteries as well as an intransigent penitential preacher who spent every ounce of his energy on nurturing the Christian roots of Europe which was coming into existence. With his spiritual energy, with his faith, with his love for God and neighbour, he truly became one of the Fathers of Europe.”12 ◊

Notes

1 ÁLVAREZ GÓMEZ, CMF, Jesús. Historia de la vida religiosa. Madrid: Publicaciones Claretianas, 1987, v.I, p.433.

2 GIANELLI, Antonio. Vita di San Colombano abbate irlandese. Torino: Fontana, 1844, p.4.

3 Idem, p.5-6.

4 SCHNÜRER, apud ECHEVERRÍA, Lamberto de et al. (Org.). Año Cristiano. Madrid: BAC, 1959, v.IV, p.433.

5 ECHEVERRÍA, Lamberto de et al. (Org.). Año Cristiano. Madrid: BAC, 1959, v.IV, p.433.

6 GUÉRIN, Paul. Le petits bollandistes. Vies des Saints. 7.ed. Paris: Bloud et Barral, 1882, v.XIII, p.530.

7 BENEDICT XVI. General Audience, 11/6/2008.

8 Cf. GUÉRIN, op. cit., p.531.

9 Idem, p.532.

10 Idem, p.533.

11 Idem, p.534.

12 BENEDICT XVI, op. cit.