Strong in her principles and mild in her ways, Mother Cabrini carried out a missionary epic, blending faith with works, in an era marked by the Industrial Revolution.

On the evening of March 31, 1889, accompanied by six disciples, Mother Frances Xavier Cabrini stepped ashore in New York. Her noble heart was set on launching an evangelizing epic, and she would have to fight to save the mission from utter ruin, before it had even started.

Due to a miscommunication, the provisions requested of Archbishop Michael Corrigan before embarking from Italy had fallen through. No one was on the wharf to meet them… Night was falling, and they knew not where to go. In that dramatic impasse, the sisters trustfully looked into the clear gaze of their foundress and at the hint of a smile that never abandoned her: everything would redound to the greater glory of the Sacred Heart of Jesus!

But for Mother Cabrini, who always blended faith with works, the moment called for immediate measures. Resolved to clear things up with the Archbishop the next morning, she accepted the dinner offered by the Scalabrian Fathers and then led her daughters to a lowly lodging. Some of the sisters slumbered as they awaited the dawn; the superior kept vigil on her knees. The distant noises of the city accompanied the murmur of her prayer…

A mission born of obedience

in the Cathedra Basilica of St. Louis (Missouri)

Ever since childhood, Frances had dreamed of becoming a missionary and of bringing the name of the Saviour to distant China. But as she matured, her longings gradually converged around a single ideal: that of uniting herself entirely with God, and being a docile instrument to carry out His will.

This generous attitude of self-giving imparted balance and audacity to her character, blending marvellously with her natural modesty. It was a combination of qualities that did not go unnoticed by Dom Giovanni Battista Scalabrini, Bishop of Piacenza – later raised to the honour of the altars – who envisioned the young religious as an efficient collaborator for his initiative in benefit of the Italian immigrants of New York.

At the time, Mother Cabrini was in Rome seeking papal approval for the rules of her missionary institute and licence to go East. In no way did the proposal of Bishop Scalabrini appeal to her. It seemed impracticable, fraught with danger, and it clashed with her most intimate desires: “The world is too small to limit ourselves to one point of the globe. I want to embrace it and go everywhere,”1 she tactfully replied.

Notwithstanding, she implored divine light and consulted persons of virtue and prudence on the matter. The persistent prelate soon returned to the topic and smiled broadly as he listened to her narrate a dream: she had seen a long procession of Saints file before her, followed by Our Lady and finally the Sacred Heart of Jesus, who said: “What do you fear, my child? You are going to carry my name to distant shores; therefore, have courage and fear not. I am with you.”2

In the end, it was the voice of the Pope that served as the compass to guide her missionary impetus and to prove the unconditionally of her obedience. Leo XIII was familiar with the plight of thousands of Italian immigrants, reduced to mere cogs in the industrial wheel of the New World. With a scanty clergy to minister to them in their own language, many had fallen away from the Catholic Faith. Beholding the charismatic religious kneeling at his feet, the Supreme Pontiff said: “Not to the East, but to the West […]. Go to the United States, and you will find the means and a large field of labour!”3

Entering America with zeal

It is easily to imagine, then, the spirit that spurred Mother Cabrini toward the Episcopal Palace, that first morning on American soil. The Archbishop received her with evident regret, explaining that he had sent a letter communicating that a series of setbacks had thwarted the plans for opening an orphanage which was to serve as their first field of action, but it had not reached them in time. “I see no other solution, Mother, than that you and the sisters return to Italy,”4 he concluded.

In the ensuing silence, Archbishop Corrigan made a quick appraisal of his interlocutor: her bearing and the look in her eye revealed a person of fibre. But little did he expect her incisive reply: “No, Your Grace, that is impossible. I have come here with the permission of the Holy See, and here I will remain. ”5

With her simple forthrightness, the question was closed, and she handed him a dossier of letters of reference from high-ranking Roman ecclesiastics.

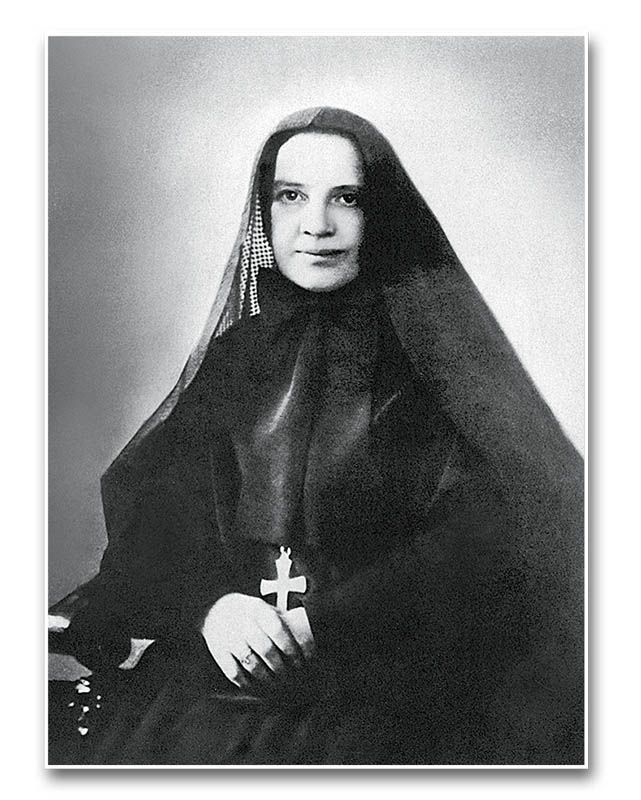

This first obstacle behind her, our Saint, “strong in her principles and mild in her ways,”6 set forth on her vast missionary enterprise. She lost no time in forging lasting bonds of friendship with Archbishop Corrigan, who, in turn, become her admirer and defender.

New York was a teeming field for her missionary ardour. The immigrants needed to be roused from their spiritual stupor, to shoulder their responsibilities as citizens of the City of God, so as to experience the consolation and strength that only the Sacraments and a life of grace confer.

The stir she awakened caught local press attention. A newspaper of the time reported: “For several weeks, a group of dark-eyed women dressed like Sisters of Charity have been seen throughout ‘Little Italy,’ climbing up narrow, dark stairways, and descending into filthy underground passages, taking the risk of entering certain forbidding places where not even the police dare to enter […] Presiding over them is Mother Francesca Cabrini, a woman with large eyes and an attractive smile. She does not speak English, but she is a woman of firm purpose. ”7

Portents of a special vocation

How different this world was from the small and affluent Sant’Angelo Lodigiano of her birth! The written memoirs of the Cabrini family include the quaint account of some relatives who set out for Rome to collect an inheritance, but as soon as they lost sight of the tower of the village church they hastily turned back, such was their regard for their hometown…

Frances was to leave this charming nook without a second glace. In only one place she flatly refused to make a foundation: Sant’Angelo Lodigiano. This attitude would shine for her disciples as the embodiment of the evangelical principle: “No one who puts his hand to the plough and looks back is fit for the Kingdom of God” (Lk 9:62).

The family had a hunch that some special plan lay in store for this engaging youngest of the numerous offspring. It was not by chance that a flock of pure white doves had settled over the family home when she entered this world on July 15, 1850. Her parents and relatives soon noted that they had a masterpiece of innocence under their care, and in due time they glimpsed something more: it was the seed of a lofty vocation of foundress, with the charism to attract, influence, persuade, mark setting and move hearts.

Missionary calling

On winter nights, the family would gather around the hearth to listen to impressive narratives from the Annals of the Propagation of the Faith. In the classroom, Frances pored over the big atlas, mentally tracing routes in far-off mission lands. At age 13, upon hearing a missionary preach, she could no longer contain her enthusiasm and confided to her sister:

“Rosa, I want to be a missionary!”

Fifteen years older, Rosa had assumed the task of giving a solid footing to Frances’ character. Concerned lest her sister turn into a dreamer, she retorted: “You, so small and so ignorant, you dare to think of becoming a missionary?”8

Frances said nothing but redoubled her faithfulness to the promises of grace within. She quietly applied herself to prayer, the reception of the Sacraments, studies and household chores, always unyielding with self and affable with others.

Years later, seeing her visit the sick, with her sister, an old engineer commented: “Ah, that one is an angel, she is not a being like us; she has something supernatural.”9 Even the formidable Rosa was to acknowledge: “Frances was perfect in exercising the virtue of obedience.”10

During the years preceding the foundation of her institute, her soul was forged by “renunciations, persecutions, incomprehension, maltreatment and the necessity of living with persons who were not drawn to the religious life.”11 While awaiting a clear sign from Providence, she was forced to temporarily sacrifice her lofty ideals, in obedience to ecclesiastical authorities anxious to put her extraordinary gifts to local use. In this crucible, she attracted and formed a core of followers, assuring them: “Be patient. You will some day be rewarded by going to the missions.”12

The long-awaited day came in 1880, through the Diocesan Bishop Domenico Gelmini: “You want to become a missionary; the time is ripe. I do not know of an institute for missionary sisters; found one.” She answered simply: “I shall look for a house.”13

Traces of her charsim

Mother Cabrini, called “un vero generale – a real general”14, rejoiced in acknowledging her own weakness and sympathized with generous souls who were prompt to admire. Her great affinity for St. Paul, shows in the motto she took for the institute: “I can do all things in Him who strengthens me” (Phil 4:13).

She practised the Jesuit principal of acting as if everything depends on self, conscious that everything depends on God; for her patron she chose the Apostle of the Orient, St. Francis Xavier, and to the Sacred Heart of Jesus she made the oblation of her being. For Mother Cabrini, enlisting in the service of the Divine Heart meant, above all, self-detachment and complete dependence on God.

An example of this detachment was the foundation of hospitals. She felt far more drawn to the education of youth than the health sector. But when in a dream – or was it a vision – she saw Our Lady with her veil pinned back, attending hospital patients in their beds, she began to erect hospitals which would become model institutions.

While on mission in Colorado, her daughters descended into the bowels of the earth to bring a word of hope to miners, reminding them to attend Mass, go to Confession and send their children to catechism class. In the prisons they rescued souls from despair, and assured the last Sacraments for inmates condemned to death.

Tireless missionary

Before initiating a foundation, Mother Cabrini strove to study the country firsthand to gain personal knowledge of its characteristics and judge the viability of the project, in collaboration with Church authorities and local needs.

Nevertheless, it was more of a supernatural impulse than any plan that drew her, in 1898, to England, which she called the Nation of the Angels. In London she noted vestiges of a Catholic past in the courtesy of passersby toward her and her religious, foreigners clothed in black. “This is how they treat sisters in England; and God, who considers as done to Himself whatever is done to His servants, will bless this nation and give it the grace of entering into the one true Church.”15

In 1901, returning from Buenos Aires, she stopped in Brazil, where she felt that “the Lord has already prepared for us a vast arena of endeavour.”16 When she sailed into the port of Santos seven years later, in 1908, she was moved to see a fleet of small rowboats coming out to meet her, carrying her dear daughters and the young students of the academy of São Paulo in a show of uncontainable joy. Her surprise and satisfaction increased when she met with a stately welcome at the São Paulo train station. She made two more flourishing foundations in the country in Tijuca and Flamengo in Rio de Janeiro.

For 23 years, Mother Cabrini traversed Europe and the three Americas, crossing the ocean dozens of times. Her congregation served at the vanguard of education, health and social assistance, areas to which the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart yet dedicate themselves on six continents.

Pope Leo XIII kept abreast of the wonderful development of this tireless missionary’s work. In her last audience with him, he said: “Mother Cabrini, you have the spirit of God. Carry it to the whole world.”17 In a previous audience, in 1898, the same Pontiff exhorted the two American sisters who accompanied their foundress: “Acquire the spirit of Mother Cabrini. Acquire the spirit of Mother Cabrini, for it is a holy spirit.”18

Embarking on the eternal mission

Living in a constant state of readiness for the encounter with her Divine Spouse, the Saint once penned these lines: “I feel myself dying of love of Thee. It is a great sorrow for me, a slow martyrdom, not to be able to do more for Thee, O my Lord! Stretch every fibre of my being, dear Lord, that I may more easily fly towards Thee!”19

Having completed the mission confided to her, the final thread separating her from definitive union with the Sacred Heart of Jesus was broken on December 22, 1917, in Columbus Hospital, founded by her in Chicago. As if in deference to her nature, death did not take her in bed, but rather alert and at work, preparing small Christmas gifts for the children patients.

Feeling unwell, and sensing that her end was nigh, she unlocked the door of her room, seated herself and rang a bell to call the sisters. When they rushed to her side she had already departed for eternity. To the very end shone her firm and lucid spirit, always more concerned with others than with self.

Her sudden passing also coincided with the impetus of her heart’s longings for Him who strengthened her: “You do know, Oh, my Jesus, that my heart has always been Yours. With Your grace, most loving Jesus, I shall follow in Your footsteps to the very end of the course, and that forever and forever. Help me, Oh, Spouse, for I want to do so fervently, swiftly!”20 ◊

Notes

1 SAVERIO DE MARIA, MSC. Mother Frances Xavier Cabrini. Chicago: Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, 1984, p.95.

2 Idem, p.100.

3 Idem, p.100-101.

4 Idem, p.112.

5 Idem, ibidem.

6 SALOTTI, Carlo. Preface. In: SAVERIO DE MARIA, op. cit., p.17.

7 SAVERIO DE MARIA, op. cit., p.119.

8 Idem, p.31

9 Idem, p.38.

10 Idem, p.42.

11 SISTERS OF ST. PAUL. Mother Cabrini. Boston: St. Paul, 1977, p.31.

12 SAVERIO DE MARIA, op. cit., p.43

13 Idem, ibidem.

14 Idem, p.73.

15 SISTERS OF ST. PAUL. op. cit., p.120.

16 SAVERIO DE MARIA, op. cit., p.307.

17 Idem, p.230

18 Idem, p.211.

19 Idem, p.118.

20 DI DONATO, Pietro. Immigrant Saint. The Life of Mother Cabrini. New York: St. Martin, 1991, p.197.