To many of our contemporaries, and even to some Catholics, the saints seem like towering mountains of virtue, superhuman beings, predestined, separated from all and from everything, inimitable in the awesome grandeur of their deeds… Yet, from the heights of Heaven, where they enjoy eternal bliss, how they must smile at such an untrue conception!

Men like all of us, subject to the same needs, vicissitudes, and miseries of earthly life, how they needed to struggle and to be supported to faithfully follow the path grace showed them! This is a reality we will have the opportunity to experience on Judgement Day. Until then, it is worth refuting some false impressions with which the devil, the world, or the indolence of our flesh seek to cloud the memory of these exemplary men and women.

One of the great lies associated with the memory of the saints is that they are isolated souls. Yes, self-sufficient people, who prayed for others without needing others to pray for them, who single-handedly converted multitudes, and who practised virtue sustained by a peculiar divine predestination…

So, for those who mistakenly believe in such assumptions, we dedicate the following story. It begins in late 1147, in Germany.

Founding of the Bingen Monastery

Hildegard, a mystic and abbess, had just founded the Rupertsberg Monastery on the banks of the Rhine, in a place that would immortalize her name: Bingen. Her prophetic writings were approved by the Pope at the Synod of Trier in 1148, and from then on, all those seeking light and solace amid life’s tribulations flocked to her. Thus, Rupertsberg soon became a veritable centre of pilgrimage for Christianity.

The collaborators of a great Saint

In the shadow of the prophetess of Bingen grew chosen souls, certainly raised up by God to make straight her paths, assist her in her apostolic tasks, and surely to sustain her in virtue. After all, Hildegard was as human as any of us, a woman weak and fearful enough to be wary of everything along the paths of mysticism, even refusing for decades to reveal what she glimpsed in the “Living Light”.

Today we know that this reserved attitude toward her own visions was not solely due to her humility. Hildegard had been poorly educated in the rudiments of writing and barely mastered the Teutonic language, much less Latin. Thus, she needed the support of a fearless, pious, and learned confessor to be freed from the fears the unknown caused her, as well as the company of a noble nun who served as her confidant, secretary, and scribe. Both, supervised by her, worked diligently on producing her first book, Scivias, whether transcribing or correcting the grammar of her writings, or translating and interpreting her visions, as she herself mentions in the work’s prologue.1

Now, who was this elect young woman?

She was Richardis von Stade, a descendant of the powerful family of the Margraves of Stade. A niece of Jutta von Spanheim, Hildegard’s former teacher, she entered the monastery shortly before the move to Rupertsberg, her mother being one of the greatest supporters of the endeavour.

A tender affection soon blossomed between disciple and teacher, and “the Saint gave Richardis the highest demonstration of her trust, sharing with her, without reservation, the sublime secrets of her heart, making her a companion and helper in her work.”2 The young follower, therefore, became something more than a daughter: a true friend, a companion in tribulations.

However, this love had to be purified from the stains of human selfishness; and the trials sent by God to Richardis, for this purpose, were the prelude to a painful melody that the future had in store for Hildegard.

An unexpected appointment

In 1151, an “election” of dubious legitimacy ended such an elevated relationship. Hildegard received word that Richardis had been chosen as abbess of a convent where she had never lived. The ecclesiastical authorities then ordered her, as was customary, to authorize the nun’s departure for her new destination: the monastery of Bassum, in Saxony.

Who orchestrated this election? And whom would it benefit? The community that had chosen a stranger? The young and inexperienced one chosen, completely ignorant of the art of dealing with souls? The interests of a powerful and wealthy family, which had no need of such honours? This was a strange case, in which nobles, archbishops, and even the Pope intervened against the desires of Hildegard, whom they had once so fervently supported…

Without understanding the reasons behind such a choice, and aided by the grace of discernment, the Saint found herself obliged to defend the vocation of her spiritual daughter. She clearly knew God’s will regarding Richardis and knew, furthermore, that she had an indispensable role in the fulfillment of her own mission. She, therefore, refused to obey that order.

Hildegard strikes back

Since that the driving force behind such an appointment might well have been the ambition of Richardis’ mother, she wrote to her in a severe and incisive tone: “The abbatial dignity you desire for them3 is certainly, certainly, certainly not the will of God, nor compatible with the salvation of their souls. Therefore, if you are truly the mother of these daughters of yours, take care to not become the ruin of their souls, to then, against your wishes, lament with bitter moaning and tears. May God enlighten and strengthen your mind and soul in the short time of life left to you.”4

She also appealed to the Archbishop of Bremen, Richardis’ brother, in moving terms: “Listen to me, prostrate at your feet with tears and anguish […]: a certain terrible man has removed our dearest daughter Richardis from my counsel and my will, as well as from those of my other sisters and friends, separating her from our cloister […]. I beg you, by Him who gave His life for you, and by His most noble Mother, to send me my dearest daughter.”5

Hildegard also wrote to the Archbishop of Mainz, who had brusquely ordered her to permit Richardis’ transferal: “The reasons alleged in favour of this young woman’s rights are invalid before God. […] The Spirit of God affirms in His zeal: ‘Oh, pastors, lament and weep at this time, for you do not know what you do when you distribute, according to opportunities for profit, the offices established by God.’”6 Later, she wrote announcing to the prelate his approaching death: “The heaven of the Lord’s vengeance has opened […]. Arise, for your days are short.”7 Deposed from the Archbishopric in 1153 – for misuse of funds, among other reasons – he died a few months after reading the prophetic missive.

Making a final effort, Hildegard appealed to the Roman Pontiff, but all was in vain: men had decided that Richardis should go her own way, even though God Himself had united them.

Yet the final blow was yet to come. The decisive step toward separation would come from the one the holy abbess least expected: Richardis herself…

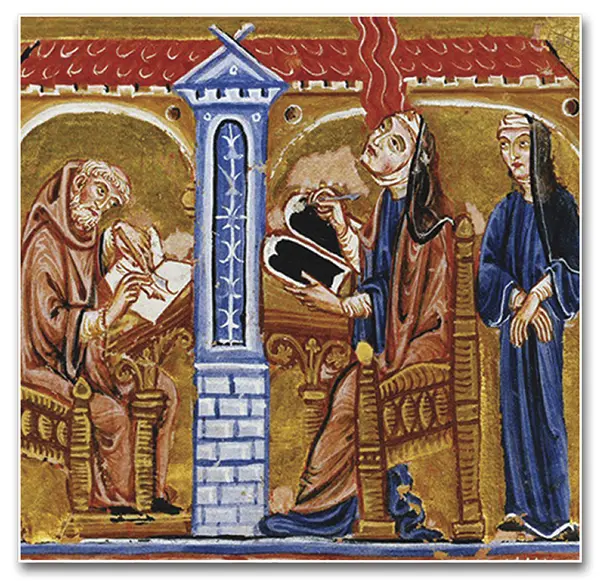

St. Hildegard receives a supernatural communication in the presence of her confessor and Richardis – State Library of Lucca (Italy)

To be a sun or a mere reflection of it?

Faced with such a complex situation, Richardis faced the great crossroads of her life: to accept the position of abbess out of self-love, or to renounce it for love of God and of her spiritual mother, Hildegard.

Under pressure from everyone, and perhaps even more vehemently from the first stirrings of ambition, she ultimately accepted the position. It seems that it was no longer enough for her to shine in the firmament of the Church as a star illuminated by Hildegard’s glory… Richardis wanted to shine on her own, to be a sun and not just a beautiful reflection of it.

Thus, after a farewell that we can imagine must have been dramatic, she abandoned her superior and set off for the monastery of Bassum.

Far from Hildegard, death

Grief then seized Hildegard with unusual vehemence, for her esteem for Richardis was based on a divine revelation. Indeed, she had learned of her pupil’s mission in a vision, and God had united them in such a way that her departure was as if her very heart had been ripped out: “Woe is me, mother, woe is me, daughter! Why have you abandoned me like an orphan? I loved the nobility of your ways, your wisdom and your chastity, your soul and your whole life […]. May all who share a sorrow similar to mine beat their breast with me, those who, in their love for God, have cultivated in their hearts and minds such love – as I have for you – for someone who was snatched from them in an instant, as you were from me.”8

Months passed, and the separation became final… eternal. Regretting her mistake and, no doubt, measuring the Consequences of her act – which would be an obstacle to the entire fulfillment of her Foundress’ mission – Richardis tearfully wished to return to her; death, however, prevented this from happening. The abbess of Bassum died on October 29, 1152. Not even a year had passed since her departure from Rupertsberg.

A work that will never be completed…

The complexity of the revelations with which Providence illuminated Hildegard’s spirit required a kindred soul capable of “translating” such supernatural communications into living teachings for the centuries to come. Anyone who has come into contact with the works left by this eloquent Doctor of the Church will have felt the lack of such a complement: visions difficult to understand or inextricable in meaning for those unfamiliar with a relationship with Heaven; a language which is captivating, yet often obscure, far removed from reality… How different these writings would be if there had been a pen to transcribe them, a capable heart to explain their mysteries!

From this lamentable episode onward, Hildegard’s life was never the same. The cross she carried, already so heavy due to its prophetic nature, became even more onerous. She needed something as human as a friendship that, purified of all selfishness, would help her fulfil her calling entirely. Thus, Richardis’ essential place was never fully occupied…9

May her life at least serve as an example to us: on the path to holiness, no one is exempt from fulfilling a mission alongside their baptized brethren, and perhaps the cross we refuse to carry today will become an even greater burden for other souls in the future… ◊

Notes

1 Cf. ST. HILDEGARD OF BINGEN. Scivias. São Paulo: Paulus, 2015, p.98.

2 HERWEGEN, Hildephonse. Les collaborateurs de Sainte Hildegarde. In: Révue Bénédictine. Abbaye de Maredsous. Year XXI. No.1 (1904), p.305.

3 St. Hildegard refers to Richardis and her niece Adelheid, also appointed abbess of a monastery.

4 ST. HILDEGARD OF BINGEN. To the Margravine Richardis. In: The Letters of Hildegard of Bingen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004, v.III, p.120.

5 ST. HILDEGARD OF BINGEN. Carta a Hartwig, Arzobispo de Bremen, entre 1151 y 1152. In: Cartas de Hildegarda de Bingen. Epistolario completo. Buenos Aires: Miño y Dávila, 2015, v.I, p.71-72.

6 ST. HILDEGARD OF BINGEN. Carta a Enrique, Arzobispo de Maguncia, año 1151. In: Cartas de Hildegarda de Bingen, op. cit., p.100.

7 ST. HILDEGARD OF BINGEN. Carta a Enrique, Arzobispo de Maguncia, año 1153. In: Cartas de Hildegarda de Bingen, op. cit., p.102..

8 ST. HILDEGARD OF BINGEN. Carta a la Abadesa Ricarda de Bassum, entre 1151 y 1152. In: Cartas de Hildegarda de Bingen, op. cit., p.195-196.

9 Hildegard enjoyed the spiritual friendship of several nuns and monks, who helped her with the same tasks until the end of her days; however, in none of them did the Saint glimpse the divine predilection that hovered over Richardis.