For more than 1,600 years his voice has resounded across the globe, testifying to the enduring worth of the lofty teachings that he bequeathed humanity.

The Word of God has irresistible power. It is the most powerful weapon that exists; a weapon of conquest and of transformation, far more powerful than an atomic bomb! A well prepared sacred preacher, who transmits the revealed word, has in his hands a true treasure of influence and of possibility for doing good.”1

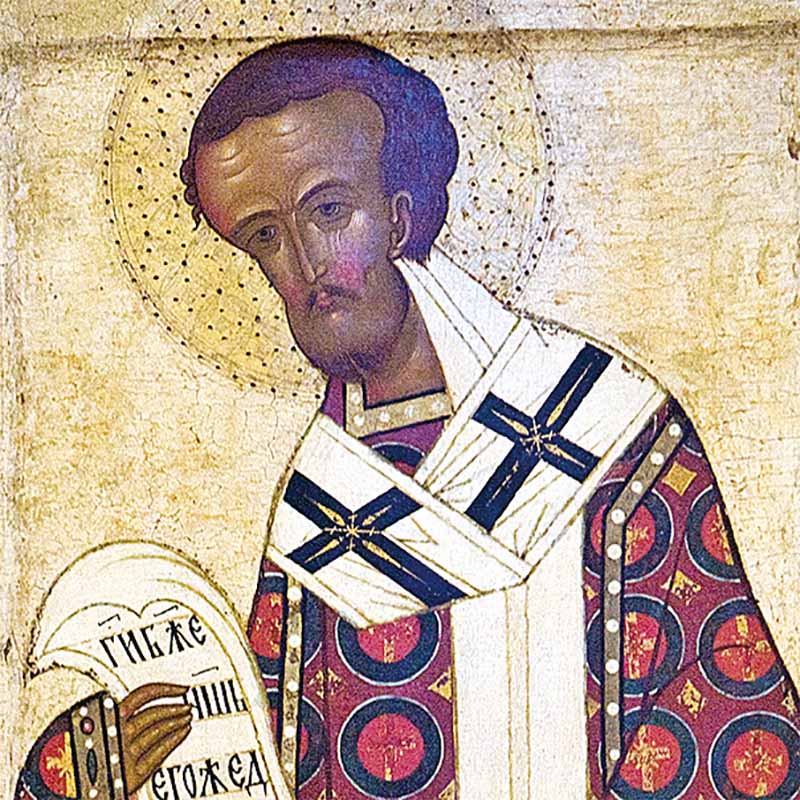

The above commentary, penned by our Founder and Superior General is an apt description of the importance of St. John Chrysostom’s life. Truly, few sacred preachers have garnered the fame that he has over the course of history. His life and especially his death are testimonies of the efficacy of his words: the wicked felt compelled to silence the “Golden Mouth,” under pain of seeing the entire Eastern world embraced by the Mystical Spouse of Christ in the early centuries of Christianity.

The gracious epithet “Chrysostom”—Golden Mouthed, in Greek—is most appropriate for this great saint who was able to present Catholic doctrine in an ardent and convincing manner, to defend the integrity of Faith and morals in those turbulent times.

Loved by all who knew him

He was born around the year 349 in Antioch, then the second city of the Eastern Roman Empire; inhabited by pagans, Manicheans, Gnostics, Arians, Apollinarians, Jews and Christians. His father, Secundus, a commander of the Eastern Imperial troops, died soon after his son’s birth, leaving his mother, Anthusa, a widow at 20 years of age, responsible for the upbringing of their newborn son.

Early on, the child revealed outstanding intelligence and was sent to two famous teachers, one of whom was Libanius, considered to be the greatest orator of his century. He received his religious education from the Bishop St. Meletius who, with his serious, gentle and attractive personality, so captivated his disciple that the latter dropped his classical studies to dedicate his life to the pursuit of spiritual perfection. At the age of twenty, Chrysostom received Baptism and the minor order of lector from this holy bishop.

The young John could have taken advantage of his illustrious birth and the rare talents received from Providence to become perhaps one of the most important men of the Empire. However, having tasted “the sweetness of the Lord,” worldly honours held no appeal for him; his sole desire was to consecrate himself to God in solitude. He embarked upon a life of austerity and prayer, and studied Sacred Scripture in depth. Dominating his choleric temperament, he attained an evangelical meekness, united with an amiable modesty, a heartfelt charity for his neighbour and a wise manner of conduct.

After four formative years in the company of St. Meletius, he withdrew to a desert place, where he lived as an anchorite under the direction of Diodorus, later the Bishop of Tarsus. There he wrote various works of a literary and spiritual nature. But in 381, with his health compromised by vigils and fasts, he was forced to return to Antioch, where he once again took up the role of lector at the side of his zealous master, who ordained him a deacon. The young John, still in the springtime of his spiritual life, found great consolation and support in the friendship of his fellow scholar, St. Basil of Caesarea.

Productive pastoral activity as a preacher

During this same year of 381, St. Meletius died. The new Bishop of Antioch, Flavian, became immediately attached to Chrysostom by the bonds of holy friendship. He ordained him a priest in 386 and appointed him as his preacher.

During the 12-year period in which Chrysostom exercised this function, his fame as a sacred orator spread. His ardent sermons on Sacred Scripture drew enthusiastic crowds who often broke out in spontaneous applause. The saint’s objective, however, was not applause—he used the pulpit to bring souls to God and God to souls. Thus, he did not mince words when it came to criticizing the evil customs of the time, whether of the simple common folk, or of the powerful, whose admiration he won from the start.

Making use of his extraordinary gift for speaking, his insightful thought, and the noble and brilliant manner of presentation, Chrysostom instructed his flock with solid principles. Free of worldly concerns, he strongly opposed the eccentric, mystical and allegorical interpretations from the so-called School of Alexandria, then in vogue.

This period of pastoral activity as a preacher was also the time of his most intense theological literary output. During these years alone, from 386 to 398, St. John Chrysostom’s work already made him worthy to be included among the first Doctors of the Church. Nevertheless, greater honours were reserved for him and, to attain them, he would have to shoulder the Cross of the Divine Redeemer.

Reforming the Clergy of Constantinople

The sumptuous Court of the Eastern Roman Emperors was seated in Constantinople, a city immersed in the opulent pleasures that economic prosperity provides. As in every age, where riches, luxury and ostentation abound, more often than not, the Christian virtues become scarce. The Archbishop Nectarius having passed away, the Emperor Arcadius wished to elevate the holy preacher to this dignity. Thus, on February 28, 397 he received his Episcopal ordination from Theophilus, Patriarch of Alexandria, and took possession of the Constantinopolitan See.

The new bishop unexpectedly found himself in this arrogant metropolis, at the head of the Byzantine Episcopate, in a setting dominated by appearances and power, often gained through secret machinations.

According to Palladius of Galatia, one of his most noteworthy biographers, St. John began his rule by sweeping the staircase from the top; that is, “to pull down the habitation of falsehood, and then to lay the foundation of truth.”2 When the Patriarch Theophilus came to know him, and observed his integrity and frankness of his homilies, he was filled with a decided antipathy.

Palladius records in the Dialogus that Theophilus, “so skilled at discerning thoughts and hidden intentions,”3 finding no point of consonance in John with his own relativistic and lax way of being, raised all forms of hostility against the new Archbishop, for “he thought it better to dominate over weak-minded men than to hear the wisdom of the prudent.”4

Meanwhile, St. John, faithful to his conscience, began to regulate the customs of the clergy, from the practice of chastity to the ownership and use of material goods. Many of the numerous monks of the diocese preferred to spend more time outside their monasteries than within. Chrysostom convinced them to return to recollection.

Kindly toward both the rich and the needy

As he had done in Antioch, he preached against worldly customs and the ridiculous extravagance of fashions, paying special attention to the widows, to whom he strongly recommended a life in accord with the laws of decorum imposed by their specific situation. These warnings provoked resentment in some ladies of the Court, who complained to the Empress.

The humble people, however, listened with awe to the noble, beautiful and, sometimes severe words of the Golden Mouthed preacher—all the more when they saw his exhortations put into practice in his own personal conduct. His concern for the needy led him to build several hospitals for the poor and foreigners; his alms were so abundant that he was called John the almsgiver.

He was so kind toward sinners, heretics and pagans, that some, with false zeal for the Faith, censured him. He, however, in a manner of paternal benevolence, urged all to penance and conversion: “If you fall into sin a thousand times, come to me, and you will be healed.”5 Nevertheless, when it was a question of maintaining discipline, he was firm and tenacious, while always avoiding roughness in his choice of words. He organized a community life for the widows and consecrated virgins, under the direction of St. Olympia, a young widow who put her enormous fortune and her life at the service of God and neighbour.

Our saint had other great friends among the wealthy. Brison, a justice official at the service of Empress Eudoxia, helped him in the instruction of the faithful and held his true friendship. The empress herself showed many signs of admiration and even devotion: she attended his sermons, took part in the processions, offered ornamental pieces for religious services and showed other displays of esteem. From the emperor, he obtained the enactment of laws that favoured the Christianization of the entire Empire.

Clashes with the Imperial Court

To destroy the influence of this man of God, the devil craftily made use of small incidents, provoking envy, egoism and organized conspiracy. He first used Eutropius, the emperor’s chamberlain. This man, who at first had experienced heartfelt admiration for the holy bishop, was a treacherous abuser of power, persecuting anyone who seemed to threaten his position. St. John repeatedly sought to dissuade him from his evil deeds, but without success. Finally, when Eutropius fell into disgrace, he sought refuge in the cathedral to evade his numerous enemies. Ignoring all the offences and disrespect he had received from this opportunist, St. John once again interceded for him, which did not please the Court.

Shortly thereafter, the Empress Eudoxia, whose influence over the Emperor Arcadius had greatly increased after the fall of Eutropius, committed a grave injustice against a widow. Chrysostom came to the defence of the weaker party, which offended the sovereign. Added to this was the conflict with the Arian Gainas, commander of the Goth mercenaries of the imperial army, who demanded a church in Constantinople for lodging his soldiers. Chrysostom vigorously opposed this insolent arrogation.

The cooling relationship between the Imperial Court and the Episcopal Palace was the harbinger of catastrophe. St. John Chrysostom’s position was a precarious one, especially because the courtiers’ henchmen felt reinforced by the emergence of new allies, including some ecclesiastics: Severian, Bishop of Gabala, who boasted of rivaling Chrysostom in eloquence; Antiochus, Bishop of Ptolemais; and, for some time, Acacius, Bishop of Beroea. All of them preferred a life filled with the Court’s attractions to the simplicity of their own dioceses.

Meanwhile, the reputation of sanctity, and the apostolic fervour, prudence and wisdom of the man of God won him the confidence of neighbouring regions. And he was invited by various bishops to preside over a regional synod in Ephesus, with the goal of designating a new Archbishop and deposing some bishops accused of Simony.

Synod of the Oak and first exile

In his absence, his rival, Severian, remained at the head of the Church of Constantinople. Chrysostom himself had entrusted him with some ecclesiastical functions in an attempt to gain his friendship. However, always vainglorious and ambitious, the Bishop of Gabala entered into conflict with the bursar of the cathedral.

The situation became more complex when Theophilus, Archbishop of Alexandria, was called to the capital by the emperor, to defend himself against certain accusations before a synod over which Chrysostom was to preside, later known as the “Synod of the Oak,” in reference to the suburb of Chalcedon where it was held. Theophilus appeared there, accompanied by 29 suffragan bishops, and seven others. When the assembly opened, he presented a long list of ridiculous accusations against St. John, who was suddenly relegated from judge to defendant. Obviously, the saint refused to acknowledge the legality of this manoeuvre and discontinued attending the proceedings. In view of his absence after three convocations, he was declared deposed from the Episcopal See and condemned to exile.

As could be expected, the people revolted and demanded his return. With a superstitious fear of divine punishment, Empress Eudoxia, who had schemed everything behind the scenes, ordered that he be reinstated. He returned and Theophilus found himself forced to flee Constantinople. But the defeat of Eudoxia only fanned the flames of her deep-seated resentment.

The “Golden Mouth” falls silent to human ears

After only two months, a new incident arose to aggravate the situation. a silver statue of the Empress had been erected in front of the Church of St. Sophia. The public games held during the inauguration festivities jeopardized the liturgical functions and drew the people into disordered and extravagant manifestations of superstition.

With his characteristic zeal and courage, the Archbishop raised his voice from the pulpit against these abuses, perpetrated under the direction of the Superintendent of Games, a Manichaean. But the empress, in a fit of vanity, took this as a personal insult. Infuriated, she once again convoked St. John Chrysostom’s enemies to depose him. Based on certain canons from an Arian synod held in 341, the episcopal partisans of the empress obtained from the emperor a decree for the banishment of St. John Chrysostom. Thus, in 404 he was led to his second exile.

Initially, the troops brought him to an isolated and rugged place on the eastern frontier of Armenia, where, however, he managed to maintain correspondence with his disciples and friends. From there, he wrote to Pope Innocent I who, indignant with the treacherous actions of those bishops, deposed several of them and addressed consoling words of support to the victim of their injustice.

Fearing a possible return of this vexing man of God, in 407, his enemies decided to transfer him to Pithyus, a place in the Empire’s outer reaches, near Caucasus. The cruel sufferings of the journey under inclement sun and rain, aggravated by the abuse of the troops, brought about the exhaustion of his already broken body. Thus, on September 14 of that year, the “Golden Mouth” fell silent to human ears, to open again only in Heaven, there to sing the glories and praise of his Creator and Redeemer.

Important portion of Holy Church’s treasure

“From the fifth century on, Chrysostom was venerated by the entire Christian Church of the East and the West, for his courageous witness in defence of the Church’s faith and his generous dedication to the pastoral ministry. His doctrinal magisterium and preaching as well as his concern for the sacred Liturgy soon earned him recognition as a Father and Doctor of the Church,”6 according to the words of Pope Benedict XVI.

Indeed, his vast work, divided into tracts, homilies and letters, represents an important portion of the inestimable treasure of the Holy Church. For over 1,600 years, his voice has resounded around the globe. His extensive extant bibliography and the countless editions of his writings are testimonies to the perennial quality of the sublime teachings he has left to humanity. St. Pius X proclaimed him patron of preachers in 1907. ◊

Notes