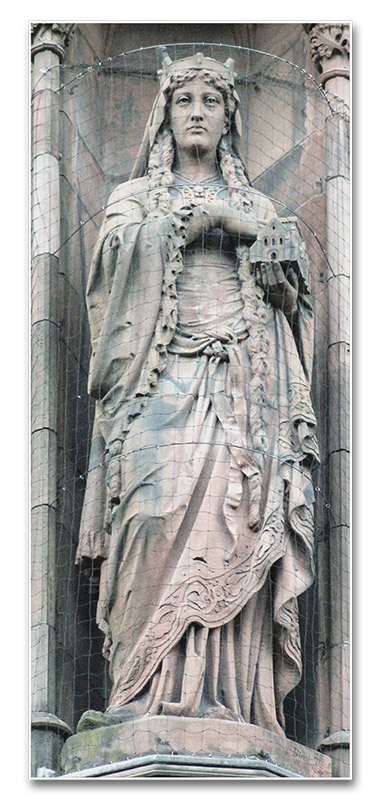

The figure of St. Margaret has that brilliance found in souls of extraordinary grandeur, capable of influencing and transforming an entire nation. She shines in the firmament of history, affirming that a joyous and marvellous world, founded on respect for God’s Law, is possible.

There is a well-known Scottish song, an unofficial anthem of the nation, whose lyrics state: “Hark when the night is falling; hear! hear the pipes are calling, loudly and proudly calling, down through the glen. There where the hills are sleeping, now feel the blood a-leaping, high as the spirits of the old Highland men…. High may your proud standards gloriously wave, … Scotland the brave.1

Situated in the far north of Great Britain, this small country is indeed rich in courage, iron-willed souls and brave hearts. If we peruse the pages of its history, we will see the exploits of a people who suffered greatly from invasions, but who resisted tenaciously. Prime examples are the heroes of the wars of independence in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Symbolic of the ruggedness of the Scots is the rocky coast that surrounds their land. Unceasingly battered by the waves of the North Sea and the Atlantic, it often seems that the waters will submerge it, such is the furore with which they strike. But when the sea returns to its bed, the cliff, intact, mocks it, as if to say: “I am still standing.”

We find this same mettle and combative spirit in the indomitable sound of the bagpipes that traditionally accompanied the Scots at war, and in the very way that they advance upon the enemy. Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira underscored this point when he saw a photograph of a Scottish soldier playing this instrument: “This man is a living depiction of heroism. The mere contemplation of his figure does more to encourage us to embrace heroism than the reading of hundreds of books. However, his state of soul can only be understood in light of the Catholic roots of this people.” 2

In order to fully appreciate this commentary, we need to go back centuries in time and contemplate the faith-filled and idealistic heart, both regal and maternal, of a queen chosen by God to be a reflection of Mary Most Holy among her people: St. Margaret of Scotland.

A providential shipwreck

Let us begin the narration by turning our gaze to a certain night in the year 1066. A frightful storm is shaking the North Sea. In the midst of the roaring and foaming waters, a fragile vessel can be detected, making every effort to stay afloat. It carries passengers of royal lineage: aboard are Princess Agatha, the widow of Prince Edward, accompanied by her children Edgar and Margaret.

The deceased prince Edward was born in 1016 in England during the reign of his father, Edmund Ironside. He was still a baby when Canute the Great invaded his country and deported him to Sweden. Later he was taken to Kiev and from there he eventually travelled to Hungary, where he married Princess Agatha, a close relative of St. Stephen. This explains the appellative by which he has been known throughout history: Edward the Exile.

He was about forty years of age when St. Edward the Confessor summoned him to make him his heir and successor to the throne of England. In 1057, he returned to his homeland, accompanied by his wife and two children, but he died a few days after his arrival.

When St. Edward also departed for eternity in 1066, the convulsions in the kingdom forced Princess Agatha to flee to the region of Northumbria, in the far north of England. Being a widow and forsaken in a foreign land, she decided to return to the continent with her children and with this intention, embarked on the ill-fated ship….

Powerless in their efforts against the wild sea, the travellers desperately sought a place to take refuge. They finally managed to make a very difficult landing at the estuary of the Forth River, near present-day Edinburgh. The ship, instead of following its intended course, had been pushed north by the storm.

She becomes Queen of Scotland

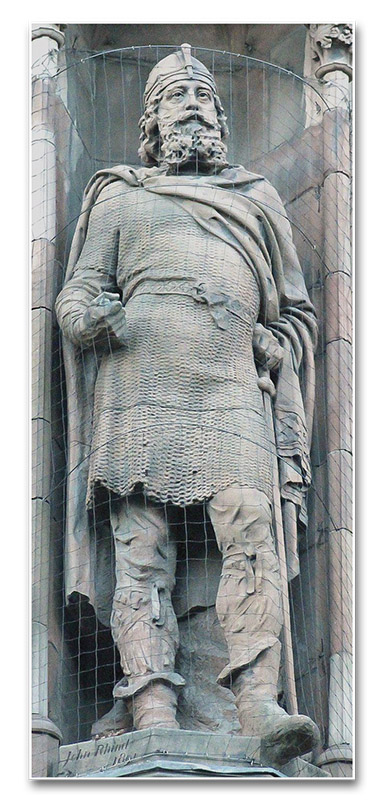

The Scottish monarch, Malcolm III, welcomed the noble family in his palace and treated them with the greatest benevolence and friendship. Impressed with Margaret’s virtue, he decided to marry her, and the young woman, although she wished to consecrate her life to God, eventually accepted. She was about twenty years of age at the time.

It was thus that she became the earthly queen of the Scottish nation, while the Blessed Virgin Mary seemed to have chosen her as mother and protector of a people who were open to the sublimities of the Faith. It seemed that Our Lady wanted to first place in St. Margaret’s hands all the graces that She would bestow on these children of hers.

The life of this queen takes us back to a wonderful world, which may seem unreal to those who do not know the transforming power of the Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Fruits of His Most Precious Blood were the innumerable Saints, both religious and laity, who, from among barbarian peoples, gave rise to the admirable Christian Civilization of the Middle Ages.

As had happened in Hungary at the time of St. Stephen and would happen in Spain and France in the times of St. Ferdinand and St. Louis, Scotland experienced the happiest period of its history under the influence of St. Margaret. Customs were established and laws were instituted that encouraged the observance of the Church’s precepts, and upon this moral foundation, the Scottish people achieved remarkable social prosperity.

Venerated as mother by her people

Turgot of Durham, Bishop of St. Andrews, confessor and principal biographer of the queen, tells us that in her person were allied labour and contemplation, elevation of spirit and a keen sense of practical things, a brilliant intelligence and an affability that led the least of her subjects to venerate her not only as their queen, but also as their mother.

“Nothing was firmer than her fidelity, steadier than her favour, or juster than her decisions; nothing was more enduring than her patience, graver than her advice, or more pleasant than her conversation.”3

With her modesty, gentleness of spirit and invariably gracious disposition, she attracted the great and the lowly, inspired respect and obedience from educated men, religious and even simple and uneducated people, uniting the kingdom around her, so as to then lead everyone to virtue and the practice of the Commandments, teaching them to be devout children of the Holy Catholic Church.

She never failed to attend to those who had recourse to her protection, hearing not only those who came to present requests, but also those who wanted to confide their difficulties, sorrows and trials to her. To help those in need, she spared no effort, even selling her personal jewels when she could not give from the royal treasure.

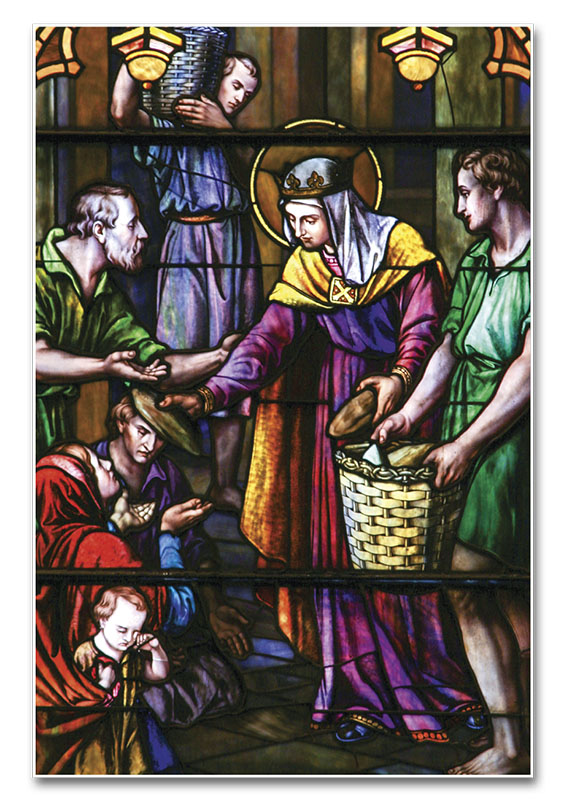

During Lent, she welcomed three hundred poor people into the castle every day and attended to all their needs, healing their wounds with her own hands. She fed them at her table, placing the men on one side of the hall next to her husband, while she sat with the women in the opposite wing.

Excellent teacher of good customs

Another historian comments that the queen was “endued by God with many excellent natural qualities of mind and body; and the happy effects of a plentiful share of his supernatural grace on her soul began to appear very early.”4

In addition to the power of influence proper to virtue, the queen guided her subjects along the good path, giving the example of an ardent and zealous piety for all that concerned the Holy Church. Accordingly, she was known by all for her great inclination to prayer and to the reading of Sacred Scripture, but particularly for her devotion to Holy Mass. She attended five or six celebrations daily, and worked so hard to improve all that was related to the Sacrifice of the Altar that her quarters in the castle seemed to be more like storage rooms for vestments and sacred vessels….

The queen also sought to enhance the splendour and pomp of the court as a fundamental means of raising the cultural and spiritual level of the people. She increased the number of serfs and servants in the castle, and established that the royal family be served at table with settings of gold and silver.

While always demanding modesty in dress from the members of the court, she introduced into Scotland the use of fabrics of better quality and with a greater variety of colours. There are historians who attribute to St. Margaret the creation of the tartan, a characteristic woollen fabric, used until today, whose colours and patterns vary according to the clan or the region to which one belongs.5

Far from wishing to incite vanity or ostentation, she concerned herself with such matters because she was well aware to what degree good customs, dignified vesture and elevation in social relations contribute to the formation of an orderly and respectful mentality, upon which peace rests.

Respected and admired by the king

Undoubtedly, St. Margaret’s zeal was dedicated, before anyone else, to the king. It was her duty as a wife to support him and help him grow in his spiritual life, but it was also her function as queen. The more a ruler progresses along the paths of holiness, the greater will be his ability to lead his subordinates to imitate him.

Thus, it was she who taught the uncultivated King Malcolm to pray and to govern with true justice. Her husband loved her and feared to offend her, such was the respect that her virtues instilled in him. He followed all her advice and gave her great freedom to use the goods of the crown in the construction of monasteries, churches or in any work aimed at strengthening the Faith.

Bishop Turgot tells us that, being unable to read, the sovereign used to take Margaret’s devotional books and kiss those that seemed most pleasing to her. And, as a sign of devotion and affection, he had golden covers with precious stones made for those she cherished most.

“May my children love and fear God”

The couple had eight children: Edward, Edmund, Ethelred, Edgar, Alexander, Edith, Mary and David. St. Margaret spared no effort in their upbringing, always vigilant about the bad inclinations that emerge at an early age.

Her maternal heart rebuked them and punished them with firmness and wisdom, but she did so with such overflowing kindness that they let themselves be shaped by her with complete trust. Thanks to her care, they became affectionate and peaceful persons. From an early age, the younger ones respected their older siblings, setting an example of the true Christian relationship that should reign among those united by the bonds of faith and blood.

Upon reaching adulthood, St. Margaret’s children did justice to the greatness of their ancestors. Three of them – Edgar, Alexander and David – became kings of Scotland, and for two hundred years the country was ruled by the sons, grandsons and great-grandsons of the holy queen. Ethelred became the Abbot of Dunkeld; Edith became Queen of England by marriage to Henry I; Mary married Eustace, Count of Bologna and brother of Godfrey of Bouillon, the conqueror of Jerusalem in the First Crusade. Edmund became a monk.

The profound love of this devoted mother for her children manifested itself with great beauty when, in the spring of 1093, she was afflicted by a painful illness and, feeling that her time had come, wanted to make a general Confession.

Shedding copious tears, she said to her confessor: “Farewell, for I shall not be here long. […] Two things that I have to desire of you: the one is that as long as you live, you remember my poor soul in your Masses and prayers. The other is that you assist my children, and teach them to fear and love God, and whenever you see any of them attain to the height of earthly grandeur, Oh! then in an especial manner, be to them as a father and guide. Admonish, and if need be, reprove them, lest they be swelled with the pride of momentary glory.”6

Wisdom and composure, until the end!

For six months Margaret was almost constantly confined to her bed. Every day her pains increased, but she endured everything with patience and prayer. She did not complain, and always remained serene.

At that time, King Malcolm had to go to war against William the Conqueror, and he perished in battle, together with his firstborn son, Edward. It is said that Margaret knew what was happening from a distance, because that afternoon she became very sad, for no apparent reason, and at a certain moment she said, sighing: “Perhaps on this very day such a heavy calamity may befall the realm of Scotland as has not been for many ages past.”7

Four days later, her son Edgar returned from battle. As he entered his mother’s room, she asked him: “Is everything well with the king and my Edward? Edgar answered, “Your husband and your son were both slain.”

Raising her eyes to Heaven, she replied: “Praise and blessing be to Thee, O Almighty God, that Thou hast been pleased to make me endure so bitter anguish, in the hour of my departure, thereby, as I trust, to purify me in some measure from the corruption of my sins. And Thou, Lord Jesus Christ who through the will of Thy Father, hast enlivened the world by Thy death, O, deliver me.”8

As she said these words, she surrendered her soul to God.

* * *

St. Margaret’s life has the external appearance of an uninterrupted succession of acts of virtue, rewarded by God with happiness and success. However, we could ask ourselves: did she not suffer terrible trials of the soul, unknown to those around her? And was not this inner holocaust the incense of sweetest odour that obtained the conversion and sanctification of her people?

We do not know. However, if St. Margaret has come down the centuries as a model mother and queen, a mirror of the virtues of the Blessed Virgin Mary, she must in some way have carried in the depths of her heart, the stark, black and cold Cross of Christ.

For her love for the Divine Master, her desire to imitate Him and to transform her subjects by the Most Precious Blood of the Redeemer, the virtuous Queen of Scotland still today radiates the brilliance proper to souls of extraordinary grandeur. She shines in the firmament of history affirming the existence of “a world where wonders are possible, and the extraordinary and the stupendous become achievable.”9 ◊

Notes