This young foundress, with a resolute soul pervaded with faith, neither feared nor fled the sufferings and hardships inherent to the consolidation of the work that Providence had entrusted to her.

“Discouragement, my father, is far from my spirit. […] Finally, believe that we are strongly convinced that we do not have the holiness required for the works of God and, therefore, for my part, I will not be surprised with any kind of failure.” 1

These categorical words, worthy of a battle veteran, flowed from the pen of a young woman of 24 years… She had just been forsaken by her spiritual director and was being counselled by the ecclesiastical superior to suppress the religious congregation that she had founded, but she treated the matter with extraordinary detachment and nobility of spirit.

Where did such fortitude come from?

Having grown up in settings that were indifferent or opposed to religion, this young foundress clearly saw the emptiness and instability of the things of this life—wealth or poverty, intelligence, pleasure and even family ties—, when the essential, faith, is lacking.

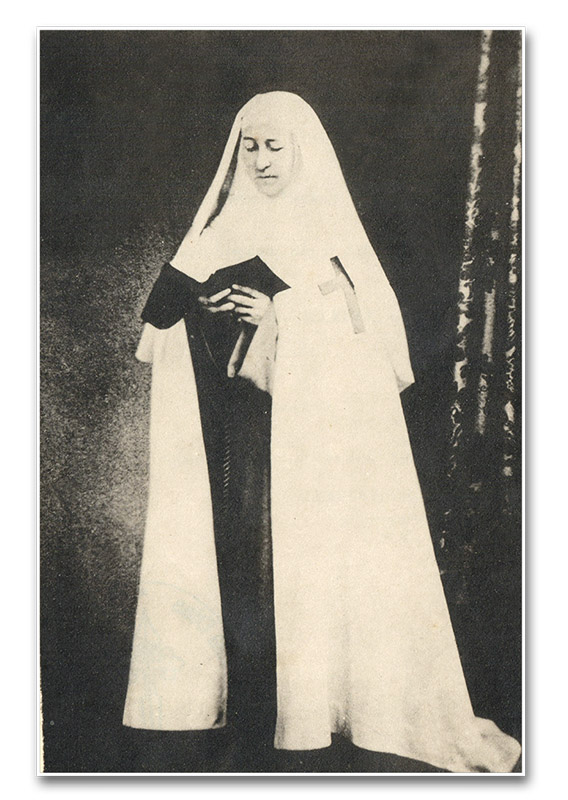

Strengthened by this principle which had been branded on her soul, St. Marie Eugénie of Jesus erected a magnificent work at the price of great suffering. Her integrity in facing difficulties was so remarkable that Pope Pius XII categorically qualified her as a “strong woman, mulier fortis, in every sense of the term: she always stood at the beck and call of the divine will; her soul was passionately devout, her heart overflowed with love of Christ, her broad, luminous, and expansive intelligence and steadfast and resolute character, was always riveted on the goal that had been set.” 2

A motto forgotten by the Millerets

Nihil sine fide — nothing without faith; not coincidentally, this was the motto of the family into which Anne Eugénie Milleret de Brou was born, on August 25, 1817. But, at the dawn of the nineteenth century, this motto would become nothing more than an evocative phrase engraved on the family insignia. Jacques Milleret, father of our Saint, chose to guide himself by the impious doctrines of Voltaire. His wife Eleonore Eugénie de Brou, descendant of nobility from Belgium and Luxembourg, seemed equally uncommitted to reviving this ideal.

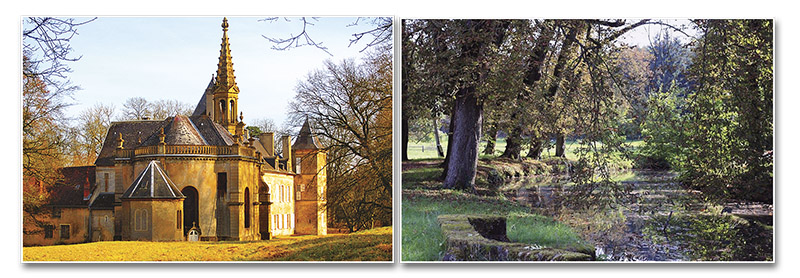

The childhood of Anne Eugénie unfolded amid serene plenty in Metz, her birthplace. Her father owned a mansion there and was also deputy for Moselle, the owner of three banks and of a large property in Preisch, where the lush countryside served as the milieu for pleasant excursions. The child frolicked freely with her siblings, and benefited from a solid education in keeping with her social standing. She spoke fluent French and German, and was instructed by her mother in the practice of the natural virtues, taking her to visit the poor and sick, and teaching her to be honest and generous.

The whole family attended some Church ceremonies together—which, at that time, was virtually a social obligation—and her life of piety consisted of little more than this. The children received the Sacraments, but their religious education was neglected. “My ignorance of the dogmas and teachings of the Church was inconceivable. All the same, I participated in the catechism classes with the other children, made my First Communion with love, and God even granted me graces which were, together with your words, the basis for my salvation,” 3 she would later write to Fr. Lacordaire.

One of these graces was granted when she received the Eucharistic Jesus for the first time. At that moment, she felt the triviality of worldly trappings, and she interiorly heard these prophetic words: “You will lose your mother, but I will be more than a mother for you. The day will come in which you will leave everything that you love to glorify Me and to serve that Church which you do not know.” 4 A vigorous seed had been planted in the soul of the young aristocrat. Years later she would see it blossom.

Radical change in family life

Anne Eugénie experienced the bitterness of grief when two of her brothers died young. But in 1830, a family tragedy produced a radical change in the life of the Millerets. As the result of unwise transactions, Jacques lost the family fortune, and was obliged to sell his property and possessions. The glittering life was over; at age 13, Anne Eugénie was obliged to leave for Paris with her mother, while her father remained in Metz with her brother Louis—only two years her senior, and to whom she was deeply attached.

Other misfortunes followed. In 1832, a cholera epidemic swept Paris, taking the life of Anne Eugénie’s mother within the space of few hours. She died without the Last Sacraments.

Orphaned at 15, she was taken in by a friend of her mother, Madame Doulcet, whose husband was the general tax collector in Châlons. Once again, she found herself in the lap of luxury. Her virtue of faith, so little nourished, wavered in a setting of chronic anticlerical conversation. But the light that had penetrated her soul at Baptism and with the reception of the Eucharist still glimmered. “God, in His goodness, left me a link of love. I may have doubted the immortality of the soul, but spontaneously rejected everything that attacked the Sacrament of the Altar.” 5

By 18 years of age, diversions no longer satisfied her. Her keen intelligence helped her to perceive that life should not be so hollow and senseless. “My thoughts are a turbulent sea which tire me, and weigh upon me. Such instability and restlessness—ardour that surpasses the limits of the possible. At times, I am absorbed by questions well beyond my reach and upon which it would be better not to dwell: the loftiest questions of the world. I want to know everything, analyse everything, and delve into intimidating realms; I boldly question everything, pursued by some sort of incessant desire for knowledge and truth, which nothing can satisfy.” 6

“I was truly converted”

At the end of 1835, her father sent her to the home of a cousin, Madame Foulon. Both she and her daughters were very devout, a fact that perhaps placed the young Milleret at greater risk of losing her faith, for they “were tedious, they seemed narrow-minded to me,” 7 the Saint would comment.

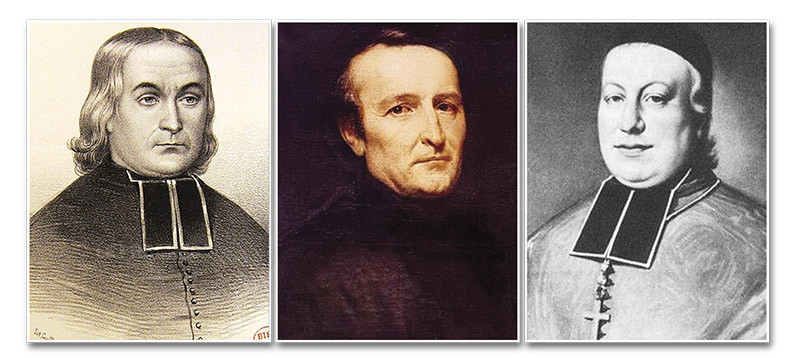

Nevertheless, it was at this juncture that Providence would strike. Following the Parisian custom in vogue, they attended the Sunday sermons of Fr. Henri Lacordaire in Notre-Dame Cathedral. He was at the height of his fame as a preacher, and his sermons deeply touched the young girl. “Your words”—she would write years later to the Dominican priest—“responded to all my thoughts, explained the best of my instincts, rounded out my understanding of things and revived in me the notion of duty and the desire for good, on the verge of expiring in my soul; in short, you gave me a new generosity, a faith that nothing could ever shake again.” 8

Anne Eugénie had found the axis of her existence. “My vocation was born in Notre-Dame,” 9 she was fond of saying. Had the trials ended? No! On the contrary, they would only intensify over the course of her life; but she had founded her faith upon the eternal rock and nothing could shake it. “I was truly converted and I was seized by a longing to devote all my strength or rather all my weakness to the Church which, from that moment, I saw as alone holding the key to the knowledge and achievement of all that is good.” 10

The young woman communicated her aspirations to Father Lacordaire and he replied: “Pray and wait.” 11 Anne Eugénie obeyed.

Dawning of the foundation

During this wait, she endeavoured “to be a man, in order to be, like them, entirely useful.” 12 This young woman, “her gaze suffused at once with virile vigour and feminine acuity,” 13 had deeply analysed the evils of the laicized society in which she lived and lamented the absence of religious formation for so many youths of the liberal aristocracy of the time: “Born into a family that was barely Christian, and educated in a society that was even less so, I was bereft of my mother at age 15 and because of circumstances of life and position, had far wider contact with and knowledge of the world than one normally has at this age. I could easily grasp the hapless state of the social class to which I belonged, and I confess to you that until this day I do not have a sadder recollection than this. It seems to me that any soul who loves the Church a little, and is aware of the deep irreligiousness of three-quarters of the wealthy and influential families of Paris, should feel impelled to do everything to make Jesus Christ penetrate among them.” 14

By now consumed with the desire to save souls, Anne Eugénie encountered, in the Church of St. Eustace, another preacher whose zeal impressed her and whom she asked for counsel: Fr. Théodore Combalot. The latter desired to found a congregation under the auspices of Our Lady of the Assumption, committed to the education of young girls, as the basis for the regeneration of society, and he saw in that 20-year-old all the qualities required of a foundress. Actually, his intentions were much bolder. He explained to her that he desired to erect a work dedicated to “rebuilding everything in Christ, to make Him and His Church known, and to extend the frontiers of His Kingdom.” 15

While touched by this proposal, she hesitated and objected: “I am unfamiliar with religious life. I have to learn everything. I am incapable of founding anything within the Church of God.” To this, the priest replied, with conviction: “Jesus Christ will be the Founder of our Association; we will be mere instruments, and in God’s hands, the weakest are the strongest.” 16

After some resistance, Anne Eugénie acquiesced to come under the direction of Fr. Combalot and, following his guidance, she waited, among the Benedictines nuns, to reach the age of majority, 21 at that time. After travelling to Lorraine to bid her family farewell, she completed her novitiate with the Visitandines and, with three other women, recruited by the same priest, began the work of the Assumption in 1839.

Comprehensive education united with faith

In the midst of the intense study program established by the Father Director, Mother Marie Eugénie of Jesus—her religious name—was convinced that contemplation was the wellspring of wisdom for the new congregation. “Education is our duty, religious life our attraction,” 17 she would say.

Having personally experienced the void that an education dissociated from faith leaves in the soul, she wanted the future educators of the Assumption to teach with their testimony of life more than by words. “Faith affords more wisdom than age,” 18 she affirmed. “It is necessary to form strong characters […]. Our mission: dynamic faith, faith dominating the reason, the inclinations, and the affections.” 19

The charism of the institute was dedication to a comprehensive education, which leads to “concern for the formation of criteria, of the critical sense, of right thinking, principally in relation to faith and confidence in grace.” 20 On the occasion of her beatification, these principles caused Paul VI to exclaim: “What a light for us Christians, who are at times tempted, in a secularized world, to separate human education from faith!” 21

Surrender to the divine will

With the long-desired foundation of the work underway, Mother Marie Eugénie was unknowingly steeling herself for the greatest sufferings of her life, coming from the seemingly least likely source—Fr. Combalot himself!

Although he was a person of generous impulses, he was a very volatile character. “He changed his mind about everything each fortnight,” 22 the Saint wrote. A case in point was his order to study the Psalms and St. Augustine, followed by a command to forsake all reading; to that of eating meat every day he juxtaposed harsh penances, interspersed with severe reprimands. Mother Marie Eugénie humbly and obediently complied with each of these directives.

Although submissive to orders, grace inspired her not to leave the direction of the foundation in the hands of so inconsistent an individual. She conveyed the situation to the Archbishop of Paris, Most Rev. Denis-Auguste Affre. The prelate was well acquainted with Fr. Combalot—whom he described as a man “of noble heart, but a hot head” 23—and he immediately understood what was happening.

To resolve the problem, he designated a superior for the community, whose appointment the impetuous priest did not accept. In fact, he decreed that the foundress and the nuns should accompany him to Brittany, to distance them from the authority of the Archbishop. The situation became very tense; on May 3 of 1841, Fr. Combalot gathered up his books and letters, and abandoned the community, never to make a reappearance.

“May God’s will be done!” 24 exclaimed the young foundress who, at 24, now found herself without the customary support, obliged to carry forward the undertaking that had been initiated. Seeking refuge in faith, she concluded: “God does not take something away without giving Himself more fully to replace it… He has shown us that the work was His and He alone wishes to accomplish it.” 25

But Providence sent her new assistance in the person of Fr. Emmanuel d’Alzon, the young Vicar-General of Nîmes, with whom she exchanged a prolific correspondence. Both desired to bring the presence of Christ to laicized society and exchanged mutual counsels in this regard. He would later found the masculine branch of the Assumption.

“I do not believe I have another vocation”

Giving new proofs of his inconstancy, Fr. Combalot sent a letter to Archbishop Affre, “as moving as it was disconcerting, asking him to take charge of the work” 26 of the Assumption. Accordingly, the Archbishop took the community under his patronage and designated Msgr. Jean-Nicaise Gros—later Bishop of Versailles—as its ecclesiastical superior. Under his orientation the constitutions and rules were drawn up, and the nuns received the definitive habit of the professed and made their first vows in his hands, on August 15 of that same year of 1841.

But a new storm was soon unleashed upon the fragile vessel. Witnessing the natural difficulties of a community that had still not attained full maturity, Msgr. Gros feared for its future and counselled the foundress to return to the Visitation Order where she had made her novitiate and which had made a favourable impression on her. As for the other sisters, each would be free to choose the religious institute to which she seemed best suited.

Mother Marie Eugénie kept her composure. She requested a brief period for reflection, after which she wrote a respectful, but forthright letter, explaining the goals, the spirit, and the characteristics of the Assumption. In closing, she declared: “I make bold to say that personal satisfaction has never crossed our mind. Our courage arose from hearing from the very lips of Monsignor the testimony that our rule was good and edifying, and from having received from his hands the holy habit, which we wear with joy and love. I do not know what we have done, in the practice of this rule, to lose the benevolence granted by your person; but if we are considered unworthy, and if this work of zeal in which we wish to labour be not accomplished by us, pardon me for taking the liberty to say it: it is a work so necessary that, sooner or later, it will be accomplished by holier hands. For my part, I believe that my vocation is none other than to belong to it, regardless of the sufferings and hardships that may ensue.” 27

Msgr. Gros’ reply was not long in coming. He showed himself to be entirely won over regarding the providential nature of the work, and affirmed: “I can only thank God for the graces He has given you.” 28

The congregation develops

At last, the Assumption had been definitively founded upon the faith and steadfastness of Mother Marie Eugénie of Jesus. The girls came, the schools spread and the congregation developed, to “form true mothers of families, to give women the broad knowledge and simple habits without which they will not know how to exercise the influence which Christianity should give them,” 29 reported the Gazette de France, evincing the hopes pinned on the new religious institution.

With the same mettle, the tireless foundress confronted other acute sufferings and obtained many victories, such as the pontifical approval of the constitutions of the Assumption, her sights ever fixed on the implantation of the Reign of Christ. Little over a century since her death on March 10, 1898, the Religious of the Assumption have communities in various countries of Europe, Africa, Asia and the three Americas, dedicated to the education of girls from all social classes.

Of this holy and fruitful life we can say with the psalmist: “Those who trust in the Lord are like Mount Zion, which cannot be moved, but abides for ever” (Ps 125:1). She was unshakable, for she trusted in the Lord! ◊

Thank you for sharing Saint Marie-Eugenie’s story! I shared snippets from her life in my blog. May many more of the youth of today find their wonderings answered by the shining Truth of the faith!