A mixture of noble and man of the people, he shows us a direct way to sanctity, loving God with his whole heart, with his whole soul, and with his whole mind; and his neighbour as himself.

The vastitudes of the New World dazzled European man at the now-distant dawn of the sixteenth century. Fertile lands, abundant natural resources and the hope of a promising future soon became an irresistible attraction for Spanish nobles, who saw the Americas as an opportunity to expand the Church of God and the realms of their king, while furthering the honour of their lineage.

The enthusiasm that spurred them on was not unfounded, for God seemed to smile on the courageous expeditionaries, filling the sails of their fragile sea vessels with favourable winds and granting success to their daring enterprises, often undertaken with the desire of conquering souls for Christ—although frequently, as well, for less noble goals.

What did Providence have in store for these vast lands, inhabited by such diverse peoples? What did He desire for those natives, alternately peace-loving and bellicose; some with primitive customs, others endowed with advanced culture and technology? Something higher than can be envisioned from a political or sociological standpoint: He desired to give them the treasure of the Faith, the Eucharistic Celebration, and sanctifying grace infused through the Sacraments.

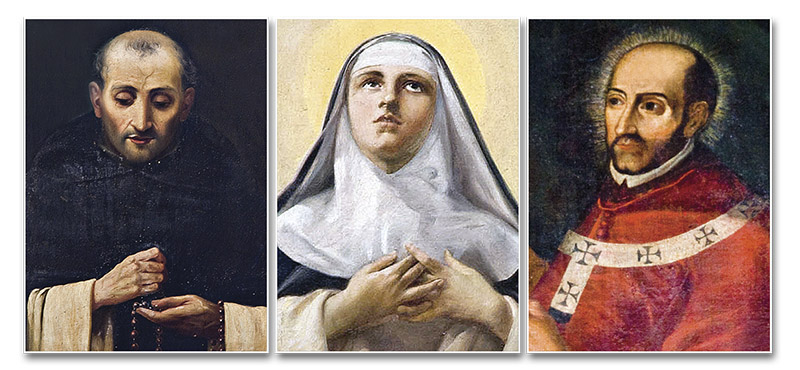

As a fruit of the heroic action of missionaries, illustrious saints began to emerge on the New Continent, gracing the new domain with the aroma of Jesus Christ and sowing the seeds of the Kingdom there with their prayers and apostolate. Let us consider 16th century Lima, which was simultaneously graced by St. Rose, third order Dominican and today patroness of Latin America, St. John Macias, the untiring evangelizer, and that exemplary shepherd St. Turibius of Mongrovejo.

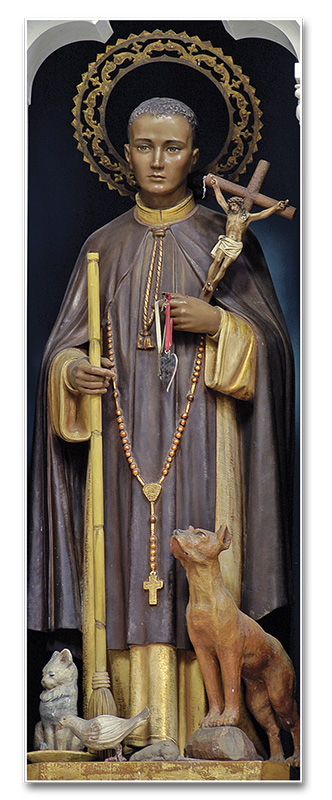

A contemporary of these three, surpassing them in the gift of miracles and in supernatural manifestations, was a humble lay brother named Martin de Porres from the Dominican convent of the Holy Rosary. “A mixture of noble and man of the people, his resplendent virtues contributed to confer on the Peruvian civilization of his time a Catholic beauty and order unsurpassed until today.”1

Desire to serve, in imitation of Christ Himself

He was born on December 9, 1579, in the flourishing Lima of the colonial era, capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru; the natural son of John de Porres, a Spanish knight, and Ana Velázquez, a free Panamanian of African origin.

In his childhood, he experienced both the demanding yet comfortable noble life with his father, in Guayaquil—present day Ecuador—and the hardworking simple life with his mother, in Lima, neither becoming attached to one standard of living nor objecting to the other. In both circumstances, he felt drawn to a life of piety, serving the altar at parish Masses or spending nights wide awake, praying on his knees before Jesus crucified.

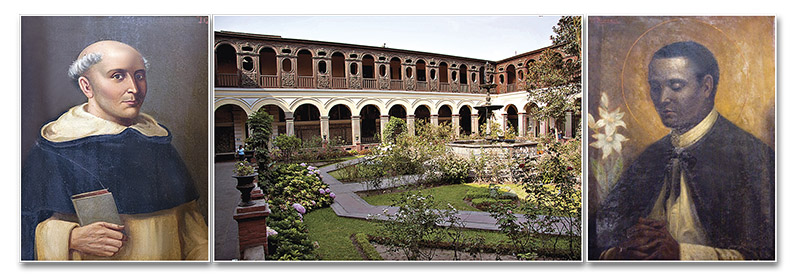

At just 14 years of age he went to the Monastery of the Rosary and presented a request to the Provincial of the Preachers, Friar John de Lorenzana. What did he seek, knocking at the door of that house of God? To become a servant of the friars, in the role of a “donado,” one of the volunteers who dedicated themselves to domestic duties and were lodged in Dominican quarters. The superior, discerning an authentic calling, was happy to receive him.

From that day on his duties include sweeping the rooms and cloisters, infirmary, choir and church of the extensive property, which housed about 200 religious, including novices, lay brothers and scholarly priests. Friar Martin was not at all ashamed of his position. His supernatural outlook helped him to clearly understand the glory of service, in imitation of Jesus Christ Himself, Who took on flesh to give us an example of complete submission.

After carrying out these arduous tasks for two years, being associated with the community only as a tertiary, Martin was summoned one day to the vestibule. There, the superior awaited him together with his father, who, returning from a long sojourn of service for the viceroy in Panama, wanted to see him again.

Indignant at seeing his son occupying such a humble position, the nobleman demanded the Provincial to promote him to at least a lay brother. The prior acceded, but Friar Martin’s eyes, instead of lighting up with contentment, glistened with tears. It was his humility clamouring within him, prompting him to implore the superior not to deprive him of the joy of serving the community as he had been doing until then.

Vocation to cure the ills of others

On June 2, 1603, he made his solemn profession of religious vows, receiving, in addition to the functions of bell-ringer, barber and custodian of the wardrobe, the care of the infirmary. There, for lack of a doctor, he also filled the role of surgeon, for he had learned the rudiments of surgery before entering the monastery.

Events soon confirmed his ability for accurate diagnosis of the sick, often contrary to appearances. For example, he announced to a patient considered to be at death’s door that he would not die then; and indeed, in a few days he was cured. On another occasion, seeing Friar Lawrence de Pareja walking through the cloister, he told him that he was about to depart from his mortal body and called a priest to administer the Last Sacraments to him. Shortly after, the friar took to his bed and died.

The countless miraculous cures attributed to him made his fame spread beyond the walls of the Monastery of the Rosary. Both the humble and the great, Spanish and Indians, rich and poor came to ask help from the holy infirmarian.

Thus, Martin’s vocation, which “seems to have been to cure the ills of others,”2 began to unfold. He spared no effort in providing good example, as well as physical and spiritual consolation in the exercise of his functions.

“He did not blame others for their shortcomings. Certain that he deserved more severe punishment for his sins than others did, he would overlook their worst offences. He was tireless in his efforts to reform the criminal, and he would sit up with the sick to bring them comfort. For the poor he would provide food, clothing and medicine. He did all he could to care for poor farmhands, blacks and mulattoes who were looked down upon as slaves, the dregs of society in their time. Common people responded by calling him “Martin the charitable.”3

Frequent supernatural manifestations

What was the source of these rare qualities? Without a doubt, it was his ardent spirituality, for “a life such as that of Martin’s, consecrated entirely to the service of neighbour, with such perfect self-denial, cannot be explained without an intense interior life, an impulse of charity which, […] even under the weight of toil, was indefatigable.”4

Late one evening, the surgeon Marcelo Rivera, a guest at the monastery, went to look for Friar Martin. He asked around for him but no one had seen him. Finally, he found him in the chapter room, “suspended in the air, with arms in the form of a cross, with his hands pressed to those of a Holy Christ crucified that was above the altar. His entire body was close to that of the Holy Crucifix, as if embracing Him. He was levitated about three metres from the ground.”5

Countless witnesses observed similar scenes. For example, one night in the novices’ building, many of the friars were unable to sleep for an epidemic had swept through, and most had been stricken with high fevers. From one of the cells, a voice moaned:

“Oh, Friar Martin! How I would like a change of tunic!”

It was Friar Vincent who, tossing and turning in bed, sweating profusely from the fever, called out to the infirmarian without any hope of being attended, for the doors were locked and Friar Martin did not live in that building. No sooner had he spoken than he saw the infirmarian beside him, holding a crisp and clean nightshirt. Startled, he asked him how he had entered.

“That, you do not need to know,” Friar Martin replied kindly, making a sign of silence with his finger.

Not far away, the master of novices, Friar Andrew de Lisón, heard Friar Martin’s voice and went into the corridor to see where he had entered. Time passed and no one appeared. Finally, he decided to open the sick friar’s door—and found him alone and fast asleep. Amazement spread throughout the entire monastery.

Friar Francisco Velasco, Friar John de Requena and Friar John de Guia received similar visits. On another occasion, a friar who was walking through the cloister saw a luminous streak passing through the air. Looking at it intently, he distinguished a flying Friar Martin, surrounded by light.

Early one morning, at the ringing of the bell, the entire community gathered in the church, as was customary, to sing Matins. Suddenly, a brilliant light coming from the back of the church illuminated the entire sacred interior. The religious turned around and discovered the source of the intense luminosity: light was streaming from the face of Friar Martin who, having come to help the sacristan, was there listening to the sacred chant.

“Praised be God for using such a vile instrument”

Many episodes such as these became public knowledge. Over time, the saint’s fame spread throughout Lima, eventually reaching the ears of the viceroy and the archbishop. But this did not disturb his humility. Never did he choose to suffer a loss of close contact with the supernatural by turning in on himself to enjoy a human glory which passes “like a dream, like grass which is renewed in the morning” (Ps 90:5).

On one occasion, he went to visit the wife of his former teacher in the barber’s trade, who was gravely ill. Inviting him to sit at the foot of her bed, she discreetly reached out her arm until she touched the edge of the saint’s habit with her hand. At that same moment she sensed she was cured and exclaimed with admiration:

“Friar Martin, you are such a great servant of God that even your clothes have the power to cure!”

With the astuteness that comes with humility, the saint replied:

“This, my lady, is the hand of God. He cured you, through the habit of our father, St. Dominic. Praised be God for using such a vile instrument to perform such a marvel, and for the habit of our father not having lost its value and holiness, even when worn by such a great sinner as I.6

“I am not worthy to be in God’s house”

Another episode, this time occurring within the monastery walls, attests to Friar Martin’s meekness in bearing with defects that sometimes surfaced in his fellow Dominicans. He accepted every suffering with utmost calm as his just deserts, and as useful for the expiation of his sins.

An elderly bedridden religious once summoned him to the infirmary, but as Friar Martin was occupied with an urgent matter, he was delayed in responding. When ten minutes had passed by, the patient became restless and began to criticize the saint, insulting him, and making unreasonable complaints.

When Friar Martin came running, begging pardon for the delay, He was greeted by an outpouring of accusations—this time proclaimed loudly, so that they were heard by other friars. In concern, some brothers gathered around, and seeing Friar Martin kneeling beside the sick man, one of them asked him what it was all about.

“Father,” the humble Brother replied, “I am receiving ashes even though it is not Ash Wednesday. This priest is offering me the dust of my lowliness, the ashes of my faults. I, thankful for this important reminder, do not kiss his hands because I am not worthy to place my lips upon them, but I remain here at his priestly feet. And I believe that this day has been profitable for me because it made me realize I am not worthy to be in God’s house and among His servants.”7

When the community suffered a time of want, the father prior was distressed at the lack of means to pay the many debts of the house. Friar Martin asked him if he would like to sell him as a slave, for by doing so he could raise a considerable sum, and he would feel honoured to have been of use to the convent. Moved by this heroic attitude of love for the Order the priest said to him:

“May God reward you, Friar Martin, but the Lord, who brought you here, will take it upon Himself to resolve the problem.”8

The way that Christ teaches us

The life of the unpretentious brother passed serenely, absorbed in long prayer vigils before the crucifix and in apparently common duties, but carried out with the intention of glorifying God, and frequently crowned by miracles. A month before he reached 60 years of age, a violent fever and frequent fainting obliged him to take to bed. Everything indicated that the end of his earthly trial was approaching.

The news spread throughout the city and his cell became a pilgrimage site. That very night, he entered his agony. Onlookers saw him struggling violently, and clasping the crucifix to his chest, rebuking the devil:

“Begone, accursed one! Your threats will not vanquish me!”

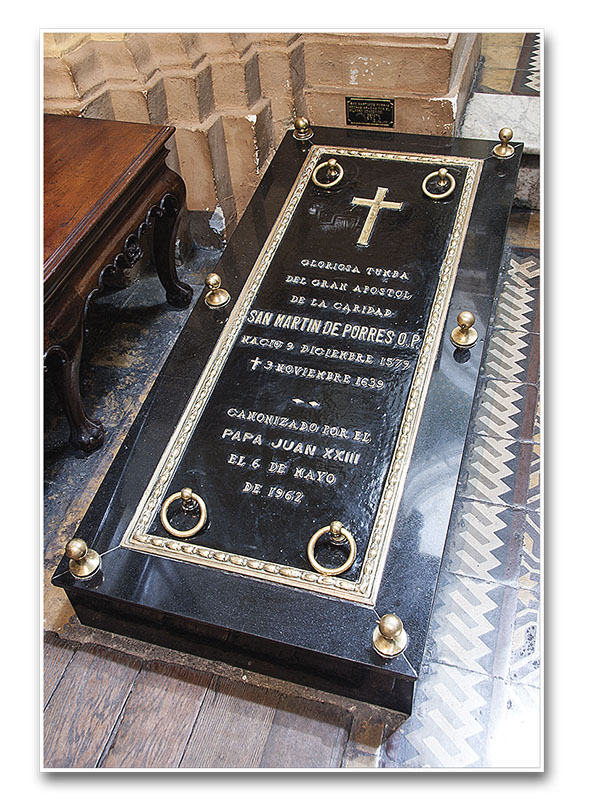

Three days later, on November 3, 1639, as his brothers of vocation recited the Creed around him, St. Martin de Porres was born to the true life, leaving a luminous legacy that until today inspires the veneration of countless faithful.

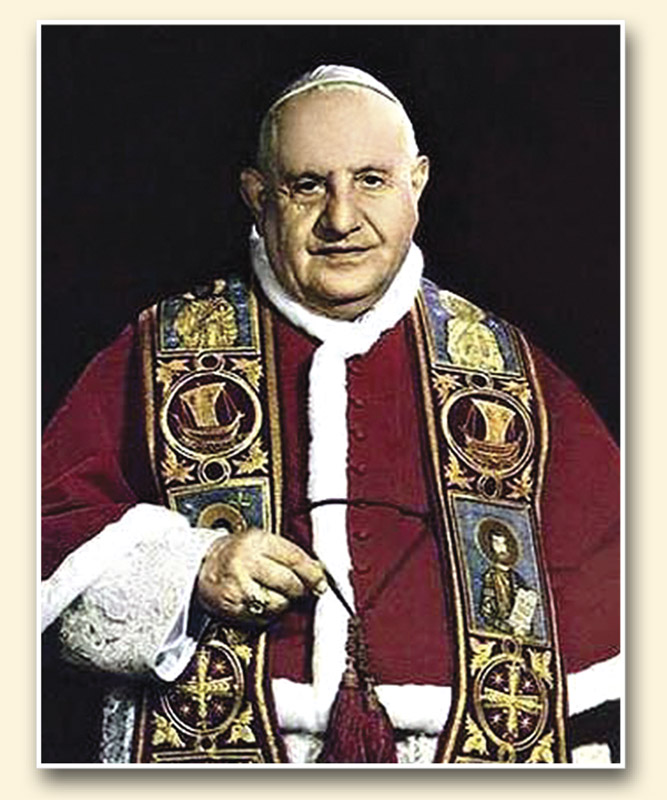

“The virtuous example […] of this saintly man extended a powerful influence in drawing men to religion. It is remarkable how even today his influence can still move us toward the things of Heaven,” recalled Blessed John XXIII upon canonizing him.9 For with the example of his life he shows us how it is possible to attain holiness by following the way that Christ taught: first, by loving God with our whole heart, our whole soul and our whole mind; and secondly, by loving our neighbour as ourselves.10 ◊

St. Martin de Porres and the Second Vatican Council

From his childhood, Martin loved God, the loving Father of all, with marks of innocence and simplicity that could not but please Him. Later, when he entered the Dominican Order, he was so inflamed with devotion that more than once, while praying with his mind free of everything, he seemed to be carried in rapture to Heaven. […]

In addition to this, Martin, always obedient and inspired by his divine Teacher, dealt with his brothers with that profound love which comes from pure faith and humility of spirit. He loved men because he honestly looked on them as God’s children and as his own brothers and sisters. Such was his humility that he loved them even more than himself and considered them to be better and more righteous than he was. He loved his neighbour with the benevolence proper to heroes of the Christian Faith. […]

Venerable brethren and dear children, as we affirmed at the outset of this homily, we find it very opportune that, in this year that we celebrate the Council, Martin de Porres will be numbered among the saints. For the path of sanctity he followed and the brilliance of the outstanding virtue that shone in his life can be considered as the salutary fruits which we desire for the entire Catholic Church and all men, as a consequence of the Ecumenical Council.

Excerpts from the homily of the Rite of canonization of Blessed Martin de Porres, 6/5/1962