O Love, you are neither known nor loved, and how you are offended!”… These mysterious and sublime words echoed through the Carmelite monastery of St. Fridian, in Florence, on a winter afternoon in 1584. An 18 year-old novice had spoken them with trembling lips and a radiant expression, her face bathed in tears.

In surprise, the sisters did not know what to think. They were well acquainted with their young companion’s piety, but had never seen her so overwhelmed, and on the verge of fainting away. They took her in their arms, believing her to be stricken by a sudden illness, and sought to calm her; but for the next two hours, she seemed to neither see nor hear anything, being exclusively absorbed by this one thought: God is Love, and is not loved!

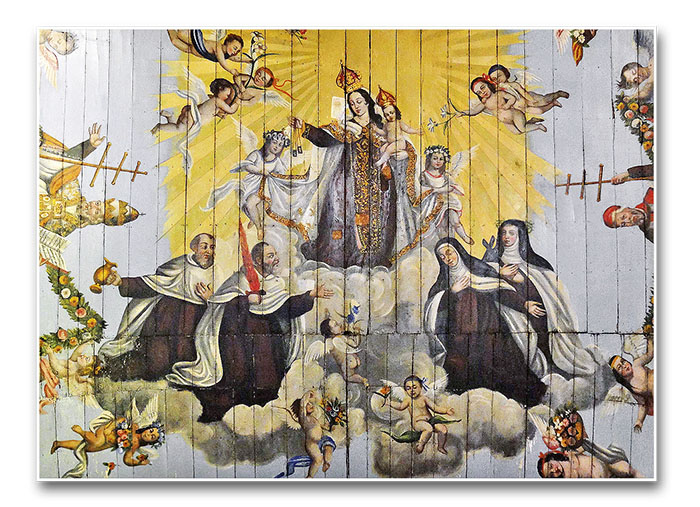

This novice was St. Mary Magdalene de Pazzi.

“Flower of contradiction”

God, the Lord of history, always attends to the needs of each era, raising up holy souls who—by their personal example, their preaching and writings, or even by opening a new way of perfection—confront the errors of their time, calling lost souls to conversion.

In the quinquecento, the Italian peninsula was characterized by an anthropological conception of the universe, in which man—with his values and qualities, but also with his deficiencies—occupied first place. To counteract this error, “The entire Italian spirituality of the sixteenth century is imbued with the theme of total love. Diverse ways joined in the common desire for theocentric love, which seemed to blossom like a flower of contradiction from the trunk of Renaissance humanism.”1

Within this context, in the city of Florence, the origin and centre of the Italian Renaissance, Catherine de Pazzi was born on April 2, 1566, in a sumptuous palace to the south of the historic Duomo, at the corner of Via del Proconsolo and Borgo degli Albizi. She was the only daughter of Camilo Geri de Pazzi and Maria di Lorenzo Buondelmonti, both from illustrious families of the Republic.

Her parents took great care in the education of this girl of rare beauty, setting their hopes on a brilliant future for her in society, where she could be expected to excel due to her natural gifts and her father’s kinship with the prestigious House of Medici. Catherine was indeed destined to stand out in the pages of history, but not exactly according to her parents’ illusions.

“I sense the sweet fragrance of Jesus!”

From childhood, Catherine showed signs of being a chosen soul. When still very small, she took greater pleasure in silence, prayer and the practices of piety than in the games proper to her age; her favourite form of recreation was teaching the Creed, Our Father and Hail Mary to children from the countryside. Endowed with great strength of will and an ardent and spirited nature arising from her Tuscan blood, she was nevertheless always obedient and affable with her parents and superiors.

Even before reaching the age required at that time for receiving the Eucharist, she fostered an exceptional devotion to the Blessed Sacrament. One day, her mother, intrigued by her daughter’s behaviour, asked her why she sometimes stayed at her side all day without leaving her for a moment. The little girl candidly replied: “Because on the days that you receive Communion, I sense in you the sweet fragrance of Jesus!”2

Considering the girl’s fervour and maturity, her confessor decided to make an exception, allowing her to receive her First Communion on March 25, 1576, at only ten years of age. Catherine’s consolation and delight knew no limits. Having once partaken of the Bread of the Angels, her soul grew in Eucharistic devotion, as in the Scriptural phrase: “Those who eat me will hunger for more” (Sir 24:21). She obtained permission to receive communion every Sunday, and on that day would count the days and even the hours.

Farewell to the world and obedience to God’s will

Three weeks after her First Communion, on Holy Thursday, while deep in thanksgiving, Catherine felt moved by divine love to promise God to act in a way that would please Him in everything. Thus, she made a vow of perpetual virginity, definitively turning her back on the smiling future that the world offered, resolved to live only for God and in God, forever.

Her parents did not see things from her perspective, and she had scarcely reached the age of 16 when they announced their desire that she should marry. Determined to be faithful to the consecration she had made to God, the young girl openly told her father that she preferred to have her head cut off than renounce her vow and the religious life for which she yearned. Astonished at such determination, Camilo de Pazzi yielded to her wishes without further objections.

His wife, however, did not give in so easily. Attached to her daughter by a merely natural affection, Maria Buondelmonti used all means within reach to deviate Catherine from her religious vocation, which she seemed to believe was just a fancy of adolescence that would soon vanish in face of appealing prospects.

But far from abandoning her resolution Catherine felt it grow in her heart, purified through waiting and trial. After several months, her mother had to admit defeat.

Ocean of consolations

The battle won and permission to enter religious life obtained, Catherine chose the Carmelite convent of St. Mary of the Angels, in the St. Fridian neighbourhood, quite simply because the nuns had the custom of receiving daily Communion. After fifteen-day trial period, she was accepted definitively on December 1, 1582. Two months later she received the habit of novice and the name Mary Magdalene, because of her special devotion to this saint.

A new dimension of life began for the young religious: on one hand, the Lord granted her the treasure of His consolations, to transform her into an apostle of His love among men; and on the other—and as a consequence of this love—He asked her to participate in the sufferings of His Passion, offering them in reparation for the evils of her day and the salvation of sinners.

The first two years spent in St. Fridian were a constant consolation for her. She felt enraptured upon contemplating the love of God for men and also understanding the horror and malice of sin, and the ingratitude of those who commit them. After some time, however, she was stricken by a mysterious illness, obliging her to remain bedridden for three months. In this state, she made her religious profession, on May 27, 1584.

From this day on, her ecstasies became continual, especially in the morning, after receiving Communion. “Seeing a flower or a plant, or hearing the Holy Name of Jesus or simply the word love pronounced in her presence, was enough to enrapture her in God.”3

“I did not know if I was alive or dead, inside or outside of my body,” the young Carmelite would later say while describing these mystical ecstasies. “But I saw God alone, in His own glory, loving and knowing Himself intimately and understanding Himself infinitely; loving creatures with a pure and infinite love; in a single indivisible union, only one subsistent God, of infinite love, absolute goodness, incomprehensible and unfathomable.”4

In Lent of 1585, the extraordinary phenomena reached their apex and on March 25, she felt the words “Et Verbum caro factum est” being engraved on her chest. On Monday of Holy Week, she received the holy stigmata of Christ in an invisible form.

On Holy Thursday, Sister Mary Magdalene became wrapt in an ecstasy that lasted twenty-six hours. Throughout the entire time in which the Passion of the Divine Redeemer was commemorated, she felt within herself, physically, the same sufferings, the same anguish and the same torments as Jesus. In astonishment, the other sisters saw her making her way through the rooms of the monastery, accompanying the Divine Master in his agony, at his judgement, and during his painful crowning with thorns. Finally, they saw her enter the Chapter room with a cross on her shoulders. She prostrated on the ground to be nailed to the wood, then, with her back to the wall and arms open, she repeated the seven last words of Jesus Crucified.

Some days later, she was permitted to witness Christ’s descent into hell, His Resurrection, and finally, His glorious Ascension.

Following the footsteps of the Man of sorrow

These extraordinary graces were to be followed by a period of intense trial and struggle. Jesus Himself announced this sorrowful stage to her beforehand, to give her the opportunity to pronounce her Fiat and to grow in union with the obedient and suffering Christ. With simplicity and confidence, she responded: “Lord, your grace is enough for me!”5

From one moment to the next, she felt herself immersed in the dark night of the soul—a veritable “lion’s cage,” in her own words, in which the infernal enemy waged war on her fortress of virtues.

The terrible trial began on the Solemnity of the Most Holy Trinity in 1585. Sister Mary Magdalene lost her appetite for prayer and all acts of piety; she experienced temptations against purity, faith, humility, and temptations to gluttony; the devil murmured thoughts of blasphemy and despair to her, even suggesting that she abandon the religious habit and flee from the community.

At other times, demons appeared to her in bodily form and beat her for hours on end. In addition to these tribulations, she bore the misunderstanding of several of the sisters who misinterpreted her behaviour and accused her of imagined faults.

She spent five years waging these battles, interspersed with short intervals of consolation. Finally, on Pentecost in 1590, she entered into ecstasy during the chanting of Matins and felt herself liberated. The devil had been unable to triumph over this soul. Then the fourteen saints to whom she was especially devoted appeared to her together to congratulate her on the victory obtained.

The spirituality of total love

The journey of this Carmelite saint is truly remarkable for the sufferings just described as well as for her continual ecstasies, her virtuous work as mistress of novices and sub-prioress, and the impressive miracles she performed during her life, such as the cure of many sick persons and the multiplication of food in the monastery.

For nearly twenty years her sisters of habit in the Convent of St. Fridian carefully gathered the words that flowed from her lips “with such abundance, that one person was not enough to write down everything that the Holy Spirit told her.”6 Six nuns were designated to conserving her precious revelations spoken in rapture. These annotations resulted in numerous and profound theological and mystical works.

Her soul was raised to such supernatural heights that she glimpsed the mysteries of God and spoke with the Three Divine Persons, as one of her confessors, Father Virgilio Cepari narrates: “When she uttered the name of the eternal Father, her voice took on a grave and majestic timbre, and her discourse was of an incomparable dignity. When she pronounced the name of the Word or the Holy Spirit, there was an indescribable sweetness that mingled with the gravity and majesty of her speech. Finally, when she spoke in her own name, her voice was lower and her words more lightly articulated, and it became clear that, in her sense of humility, she wanted to annihilate herself before God.”7

The spirituality of St. Mary Magdalene de Pazzi was centred upon what she called “dead love.” She described this as being the final degree on the scale of perfection, in which the soul who possesses it “does not desire, want, yearn for, or seek anything. […] By complete surrender, one dies to oneself in God, not wishing to know, understand or experience Him for oneself. The soul wants nothing, knows nothing and desires no power to do anything. […] Sorrow is not sorrow for such a soul, and it does not seek glory, but lives in everything as if dead.”8

Consummation of love

This love translates into an insatiable thirst to save sinners and conquer souls for heaven. From within her convent, Mary Magdalene was deeply pained to hear of the growth of heresies and their considerable influence in society. Her ardour for the conversion of the Church’s enemies led her to desire to remain on earth for a long time, so as to work and steep herself in mortification for this intention: “To suffer, not to die!” she frequently exclaimed.

Yet Jesus and his most holy Mother did not delay long in calling this chosen daughter to themselves and to finally grant her the complete possession of the union of love, of which she had experienced a foretaste here on earth. At her request, the final years of her life were devoid of mystical consolations; they were filled with sufferings brought on by the illness that shortened her days: coughing, fever, haemorrhaging and headaches. Finally, on May 25, 1607, at 41 years of age, she surrendered her beautiful soul to God, after having received Holy Viaticum the previous evening, and having solemnly requested pardon of her faults from the entire community.

Her luminous journey and her message for posterity can be summed up in these words springing from her loving heart: “Without Thee I could neither live nor be happy. […] If I were given all the happiness possible on earth, with all its pleasures; if I were given the fortitude of the strong ones, all the wisdom of the wise and the graces and virtues of all creatures, without Thee, I would consider it a hell. And if I were given hell itself with all its pains and torments, but with Thee, I would consider it a paradise.”9 ◊

Notes

1 YUBERO, Alberto. Introduction. In: SANTA MARIA MAGDALENA DE PAZZI. Éxtasis, amor y renovación. Revelaciones e Inteligencias. Renovación de la Iglesia. Madrid: BAC, 1999, p.XX.

2 VETTARD, Th. Sainte Marie-Madeleine Pazzi. In: Un Saint pour chaque jour du mois. Paris: Maison de la Bonne Presse, 1932, t.V, p.226.

3 CEPARI, Virgile. Vie de la Sainte, apud BRANCACCIO, Laurent-Marie. Introduction. In: SANTA MARIA MAGDALENA DE PAZZI. Oeuvres. Paris: Victor Palmé, 1837, t.I, p.XIII.

4 SANTA MARIA MAGDALENA DE PAZZI, Vita, c.II, n.22, apud ROHRBACHER. Vidas dos Santos. São Paulo: Américas, 1960, v.IX, p.245.

5 VETTARD, op. cit., p.230.

6 CEPARI, op. cit., p.XIV.

7 Idem, ibidem.

8 SANTA MARIA MAGDALENA DE PAZZI. Revelaciones e inteligencias. In: Éxtasis, amor y renovación, op. cit., pp.158-159.

9 ROYO MARÍN, OP, Antonio. Los grandes maestros de la vida espiritual. Madrid: BAC, 2002, p.319.