A model of meekness and humility, he was always attentive to the voice of the Shepherd, Who instructed him in divine science and the secrets of true sanctity.

Those who have ever witnessed the enchanting spectacle of a flock of sheep gathered around its shepherd will certainly have noted how there is a type of exchange between these meek animals and the one who cares for them. In fact, when he calls or admonishes them, the sheep submissively and attentively cluster around him, apparently grasping the meaning of his words.

Such an apparently simple scene reveals to us the profound truth of the Gospel phrase: “My sheep hear My voice” (Jn 10:27). There is in the shepherd-sheep relationship a symbology created by God to help us understand the relationship, filled with consonance and intimacy, between Jesus and the soul that is guided by grace. A word, which is to say, a gentle prompting of the Holy Spirit, is enough to move the soul according to God’s will, with neither fear nor doubt, for it recognizes the timbre of the Shepherd’s voice.

Such are the saints, throughout history, the true “oves manuseius—the sheep of His hand” (Ps 95:7), pliant and obedient to His commandments. What distinguishes them from other men and helps them to scale the heights of virtue, conferring on them an unmistakable charism of attraction, resides in this surrender in God’s hands and their docility in allowing themselves to be guided according to His good pleasure. This is true heroism which far exceeds efforts and works in which the soul may exhaust itself, for these, when deprived of the assistance of grace, are entirely barren.

We understand, then, that holiness is not so much a matter of accomplishing great works, but rather of making all works great—even the most insignificant.

Contemplative from infancy

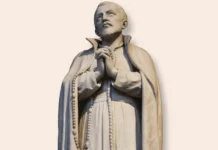

On a jubilant Pentecost Sunday in 1540, while the pealing of the bells of the parish church of Torrehermosa in the Province of Zaragoza, Aragon, commemorated the great solemnity of the Holy Spirit, a child was born. He was predestined by God to be a perfect model of meekness and innocence, like a lamb of the Lord’s flock. Since this day is called “Pascua de Pentecostés” in Spain, his parents, Martin Baylon and Elizabeth Jubera, baptized him with the name of Paschal.

From a humble background, little Paschal began working at seven years of age, to help his parents who were honest farmers. He pastured their sheep—their sole possession—and later fulfilled the same task for other landowners.

The solitude of the fields and the customary serenity of the flock made an ideal setting for the development of his austere and contemplative soul, helping it to flourish with virtue. From his earliest years, his parents had sown in him the seeds of ardent piety, which Paschal strove to cultivate through assiduous prayer, mortification and reading. The family lacked the resources to send the boy to school, but still he learned to read and write on his own—or was taught by the Angels, according to some of his biographers—to feed his desire to learn about the Faith. His backpack became a little library, where he carried his devotional books and the Little Office of Our Lady, which he prayed every day.

Since the little shepherd was unable to attend Mass during the week, he filled this void by spending long hours in prayer in a little hermitage of the Blessed Virgin Mary located in the region, or with his face turned toward the distant Shrine of Our Lady of the Hills, or quite simply before his own staff, upon which he had engraved a cross and an image of Mary. God was pleased and rewarded him, allowing the Angels to bring the resplendent Host to him on several occasions so that he could see and adore it.

However, as the region surrounding the hermitage was arid and the pastureland scarce, Paschal’s master warned him that his flock would eventually perish if he kept going there. But loath to give up his favourite spot the child replied, with robust faith, that Mary, as God’s Shepherdess, would not let the flock go without feed. As time went by, the owner was persuaded, for he could see for himself that his sheep were the most well-fed in the entire region.

Entering religious life

Since Paschal ardently desired to give himself over to God in the religious state, St. Francis and St. Clare appeared to him one day, and told him that he should enter the Order of Friars Minor. This mandate coincided perfectly with his most cherished wishes, for he fostered a special love for the virtue of poverty. And when his patron, Lord Martin Garcia, a rich and powerful man, promised to leave him his possessions, since he had no children of his own, the young shepherd declined the offer, saying that he preferred to be the heir of God and the coheir of Jesus Christ.

At twenty years of age he went in search of this incorruptible inheritance, travelling to the kingdom of Valencia. He wanted to enter the monastery of Our Lady of Loreto, recently reformed by St. Peter of Alcantara. But his timidity kept him back for four years from speaking with the Father Superior. During this time he remained on the outskirts of the monastery, once again employed in guarding the sheep. His piety and his virtue won him renown over the whole countryside, and gained him the nickname, “holy shepherd.” 1

He finally resolved to request admission to the monastery, and was joyously welcomed by the community. The Superior wanted to give him the habit of choir brother, but out of humility Paschal begged to be left as a simple lay brother, since he wanted nothing more than to be the “broom of the house of God.” 2

Humility and intrepidity

The new friar was quick to become a model of religious observance, and various convents of the Order vied for his presence. He fulfilled an assortment of tasks—including cook, gardener, porter and almoner—with detachment and simplicity. The more he sought to humble himself before men, the more he grew in spiritual stature before God. While he was affable and kind with others, Brother Paschal was harsh and demanding with himself. He considered himself to be a great sinner, and accordingly made constant sacrifices, depriving himself of bread in order to give it to the poor, sleeping on the bare ground and frequently scouring himself.

One of his contemporaries said of him: “He never thought of satisfying the least caprice. He always strove to mortify himself. Humility, obedience, mortification, chastity, piety, kindness, modesty; in short, all the virtues shone in him. I would not be able to say with certainty that one stood out over the others.” 3

He fostered a tender devotion to the Blessed Virgin, to whom he dedicated all of his works. One day as he was setting the table in the refectory, and believing himself to be quite alone, he fell to his knees before the statue of Our Lady. Then, seized by a supernatural ecstasy of joy, he performed a quaint dance for that Mother who had blessed him with so many consolations. This episode was witnessed by another friar, who later told of it, adding that the remembrance of it, as well as of Brother Paschal’s radiantly joyous face, encouraged him in the practice of virtue for a long time.

In 1576, his superiors sent him to Paris as the bearer of an important document for Fr. Christophe de Cheffontaines, Superior General of the Order. At that time, France was torn by religious wars and there was evident danger in going through cities wearing the coarse woollen habit of St. Francis. But intrepid Brother Paschal embarked on the venture filled with confidence in Providence and glad to put his life at risk for obedience. In some places he was stoned by Huguenots, and until the end of his life would bear a shoulder wound.

When he returned to the friary, he made little account of the dangers he had confronted, answering his confreres simply and omitting details that might have garnered him praise.

During his many walks through the towns and villages of the region, gathering alms for the monastery, his words were as good as a sermon to all who heard him, and his miracles won the admiration and respect of the people. He worked the cure of countless sick people by making a simple Sign of the Cross. On one occasion, the Father Superior ordered him to heal a friar who was seriously afflicted by a haemorrhage. Even though this order wounded his humility, our saint felt obliged to obey. He traced the Sign of the Cross on his companion and the blood soon stopped flowing.

Special Eucharistic devotion

Nevertheless, what was most outstanding in our saint was his devotion to the Blessed Sacrament. The moment his duties would let him, the humble brother would take refuge close to the tabernacle, sometimes praying with his arms in the form of a cross, or at other times, lost in profound adoration, or even fervently serving the private Mass of some priest from the monastery. It was near the Eucharistic Jesus that his soul expanded and gathered new strength to face life’s struggles. There, the Divine Master revealed to him the mysteries of the Kingdom, hidden from the learned and doctors. Without have completed any studies, the humble Franciscan lay brother understood more theology than many masters, for the ardour of his heart explained what could not be grasped by reasoning.

This became evident on one occasion, in France, while he was being interrogated by some heretics regarding the Real Presence of Our Lord Jesus Christ in the Blessed Sacrament. He confronted the sophisms of the enemies of the Faith with such wisdom and gave them such a perfect explanation concerning the doctrine of the Eucharist, that they felt cornered and speechless. Those who accompanied Friar Paschal were also awed, for they knew that he was not a man versed in letters, much less in religious studies.

Even during commonplace, routine work, his heart was always focussed on the tabernacle. For example, while tilling the soil or cooking vegetables, he prayerfully recalled his morning Communion: “O Light without stain, what delight can You find in such an insignificant man as myself? Why do You wish to enter my breast and make of it a temple for Your Majesty?” 4 His soul was eager at every moment to adore God in the Eucharist.

Complete attention to the Shepherd’s voice

St. Paschal died in 1592, at 52 years of age, in the monastery of Villarreal, after an illness that caused him to suffer for five years, providing him with an opportunity to edify all those around him with his patience.

Shortly before dying, he asked the brother nurse: “Has the bell for the conventual Mass already rung?” 5 When he was told that it had, his face lit up with a jubilant smile, for he had been given prior knowledge of the hour of his departure. At the moment of the elevation, when the altar bells announced the Real Presence of Jesus on the altar, the humble brother exhaled his last breath and his soul took flight to permanently join the very same Jesus Whom he had sought so earnestly throughout his life.

His reputation for holiness had become so widespread that his funeral was delayed for three days because of the influx of people coming to the friary to bid him farewell. During the funeral Mass, to the amazement of all present, his eyes opened twice—at the elevation of the Sacred Host and again when the chalice was raised, in reverence to the Blessed Eucharist for the last time on this earth.

Like a meek lamb of Christ’s flock, St. Paschal Baylon knew how to focus his entire attention on the voice of the Shepherd, who instructed him in divine science and in the secrets of true holiness. In fulfilling the vocation of a Franciscan lay brother, his life was spent in the peace of the cloister and in mendicancy; in a humble and hidden but courageous manner, continuously and exclusively seeking the glory of God. And great glory and worldwide renown was reserved for him. He was canonized by Innocent XII less than a century after his death, on July 15, 1691, and very fittingly proclaimed Universal Patron of Eucharistic Congresses and Works by Pope Leo XIII, on November 28, 1897. ◊