The Heart of Jesus called her to found a congregation in His honour, but He allowed that there she become anonymous. It was amid silence, suppression and suffering that she attained the plenitude of heroic virtues.

When we analyse the lives of the Saints, we are inspired in contemplating souls who, enkindled by the flames of the Divine Holy Spirit, do not retreat before the bitterest disappointments or defeats. The audacity of their goals, the intransigent opposition they faced in attaining them, and their intimate union with Our Lord as their support to endure poignant sufferings, makes these scintillating stars shine in the firmament of holiness.

Let us not imagine, however, that this type of vocation is always marked by the abundance and grandeur of their works, for Our Lord teaches that “In my Father’s house are many rooms” (Jn 14:2). Of some souls He expects prodigious works; others He calls to renunciation and sacrifice, or even to being victims of their own failure. All are great in the eyes of God, who does not judge by outward appearances, but by docility to His plans.

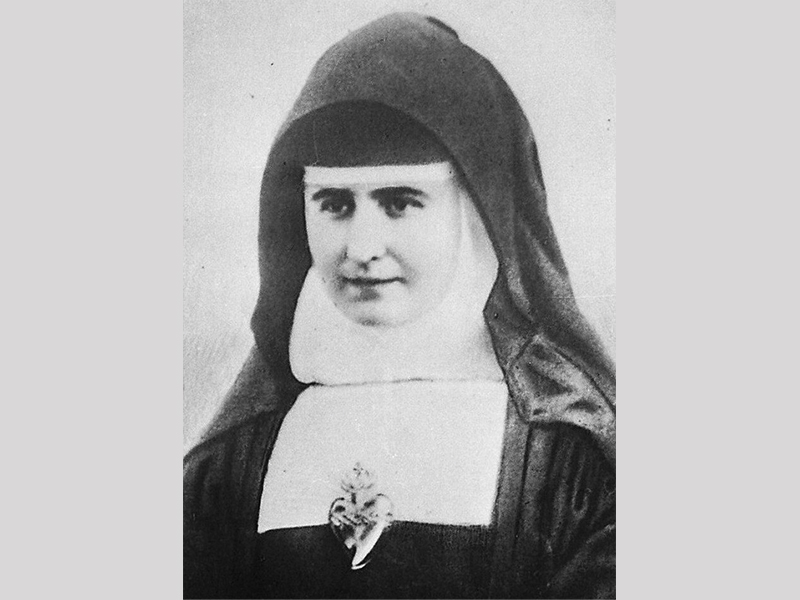

St. Raphaela Mary of the Sacred Heart is one of the most beautiful examples of absolute abandonment into the hands of Providence, for she was asked to see herself relegated to apparent futility, while her heart burned with the desire to conquer the world.

A soul made for the supernatural

Raphaela Mary Porras Ayllón was born in Pedro Abad, in the Andalusian province of Cordoba, Spain, on March 1, 1850. Her parents, fervent Catholics of considerable wealth, took care to educate her in the love of virtue and the practice of the Commandments.

Her first years unfolded in the tranquillity of her native village and, despite having many siblings, circumstances dictated that from the age of seven onward, her only companion in work and play was her sister Dolores, four years her senior. Her life was like that of many other young girls her age, although she seemed more suited to the contemplation of heavenly things than for earthly concerns.

At age fifteen she gave her heart to God forever, secretly making a perpetual vow of chastity, in St. John of the Knights Church. It was March 25, 1865, feast of the Incarnation of the Word, in which the “fiat” of the Blessed Virgin as “Handmaid of the Lord” (cf. Lk 1:38) is commemorated. By the time the family began to make marriage plans for the young Porras girls, the two sisters had already chosen “the better part” (cf. Lk 10:42).

Religious vocation revealed

God wanted Raphaela to follow the way of abandonment in His divine hands. Therefore, at each step, He demanded of her complete detachment from earthly things, as she herself comments regarding an episode that occurred when she was eighteen years of age. “Some episodes from my life, in which I saw the evident mercy and providence of my God: the death of my mother, whose eyes I closed, since I found myself alone with her at that moment.” This incident, she adds, “opened the eyes of my soul, producing in me such disillusionment that life seemed like an exile. Holding her hand, I promised the Lord that I would never place my affection in any earthly creature.”1

With the passing of the months, the life of Raphaela Mary, as well as that of her sister, was radically transformed. They spent time together at the bedside of the poorest and those with the most repugnant illnesses, praying the Rosary or distributing alms to those in need. There was plenty of objection from their own family, as Dolores relates: “Entirely orphaned and much persecuted by our closest relatives, my sister and I, after four terrible years of struggle, decided to become religious.”2

Which religious institute should they enter? Many possibilities were open to them. In 1874 they moved to Cordoba, where they had at first thought of becoming Carmelites. Nevertheless, they spent some time in recollection in the Clarist convent and at the insistence of some diocesan ecclesiastical authorities they eventually made arrangements with the Visitandine Sisters, so as to establish a boarding school in the city directed by the Visitation Order.

It was then that they met Fr. José Antonio Ortiz Urruela, a priest who would guide and accompany them during the first steps of their vocation, and it was upon his counsel that they joined the Society of Mary Reparatrix. It was a new institute, not subject to strict monastic cloister, which aimed to unite Eucharistic devotion to the duties of apostolate, at the service of the universal Church.

From novice to foundress

In March of 1875, some religious of this congregation from Seville relocated to Cordoba to found a novitiate, making use of the spacious building that was offered to them by the Porras family. The two sisters began their postulancy there and, before long, other young women followed their example.

Following the custom of the time, upon receiving the habit, Raphaela and Dolores were to change their name to signify the new life that they were now beginning. They were called, respectively, Mary of the Sacred Heart and Mary of the Pillar.

For them, the life of a novice was like a taste of Heaven on earth. Everyone admired the humble virtue of Raphaela and sensed the special calling that Providence had reserved for her. Nevertheless, innumerable perplexities awaited them…

In 1876, after a series of disagreements with the new bishop, the Reparatrix Sisters returned to Seville. However, Raphaela discerned that God wanted her in Cordoba, even though this would imply the creation of a new institute. In order not to impose her opinion on the others, she remained silent on the matter.

For the other novices, their choice was clear: they would do whatever Raphaela did. It was her example that had attracted them to the religious life and they wished to continue under the same inspiration. When they learned that she and Dolores would remain in the city under the direction of Fr. Antonio Ortiz, they decided to remain with them. Only four novices followed the religious of Mary Reparatrix to Seville.

To her surprise, Raphaela was appointed superior of the new institution. It had never passed through her mind that she would give orders to anyone, especially to her own sister. Dolores was of a very lively temperament, intuitive and gifted, and it was said that if need arose, she would have been able to govern a kingdom. However, she had accustomed herself to obey and to listen.

In accepting the office that was imposed upon her, she did only what she had done all her life: she submitted to what others thought best. From that moment, she was at once a novice and the mistress of novices. To Dolores fell the duty of administrating the temporal goods of the community, which she executed with perfection. Thus, the two sisters became the foundresses of the nascent institute.

First obstacles

When the first ceremony of profession of vows approached, an obstacle arose: the Bishop, Zeferino González y Díaz Tuñón, OP, wanted to examine the constitutions and introduce several modifications to them, for he desired to impart a more Dominican note to the new institute. He considered daily exposition of the Blessed Sacrament excessive, and wanted to subject them to a stricter regime of cloister and to make alterations to the habit. And he gave them twenty-four hours to accept the changes he proposed.

Nevertheless, God had inspired in the heart of the foundresses that they should adopt the rules of the Company of Jesus and, in learning of these impositions, the novices clamoured in one voice: “We want the rules of St. Ignatius.”3

The only solution was to relocate to the neighbouring city of Andujar, belonging to the Diocese of Jaen. They did this at night, without prior notice and in full agreement among themselves. Arriving at their new destination, they lodged in a charitable hospital. Some days later, an agent for the local authority appeared in search of the religious who had disappeared from Cordoba, accusing them of being smugglers! The denunciation was so ridiculous that the religious could not suppress a laugh…

Through these and many other difficulties, Raphaela Mary was the “most joyful and the one who provides the most joy to others,”4 the novices said, even though interiorly she was pervaded with suffering and perplexity.

The life of the new congregation

After several comings and goings, the “fugitives” finally settled in Madrid, where the Archbishop Primate of Spain, Cardinal Juan de la Cruz Ignacio Moreno y Maisanove, welcomed them. The new congregation was approved by him under the name Institute of the Sisters of Reparation to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, which the Vatican later changed to the Handmaids of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

The apartment in which they established themselves in the city centre brimmed with enthusiasm, although it was utterly impoverished. It was so poor that anyone who wished to visit them was advised to bring their own chair…

Their principal devotion was to the Holy Eucharist, and so they immediately requested authorization to reserve the Blessed Sacrament in their chapel. However, this permission depended on Rome. Undaunted, Raphaela straightaway wrote to the Pope in the following terms: “Humbly kneeling at the feet of Your Holiness, we insistently implore and beseech thee to grant us the inestimable grace to reserve Jesus Christ in the Blessed Sacrament in our chapel, as our main consolation and the principal reason for our gathering.”5

She was told that everything from Rome comes slowly… But Providence found a way to heed the desires of the young devotees in an unexpected manner: at the end of daily Mass, the chaplain would unintentionally leave some particles on the paten or the altar cloth and the exultant religious would spend hours adoring those small fragments of Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament. The fact was inexplicable! “The more care I took in cleaning the paten, the larger were the particles that remained,”6 commented the pious priest.

Rooted in Eucharistic fervour and devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the institute grew. By 1885 it had almost a hundred religious. The foundations multiplied, and the works of apostolate flourished, including: “schools open to all, colleges, houses for spiritual exercises, Marian congregations and adorers of the Blessed Sacrament.”7 The new association gradually took on the characteristic desired by St. Raphaela Mary, of being: “universal, like the Church.”8

The virtues of Raphaela’s soul also intensified and came to be qualified as “humility incarnate.”9 She impressed upon her spiritual daughters the need to be united to confront future trials: “Now, my dear ones, as we are in our foundation, let us lay it down solidly, so that the future storms do not bring down the building; and remain closely united, without leaving the least crack by which the devil can introduce a claw of division. All united in everything, like the fingers of a hand, and thus we will obtain everything that we desire, for we have God, Our Lord, on our side.”10

The storms of division

However, it was not long before the storms of division struck the sacred edifice of the Handmaids of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Unjust criticisms, misunderstandings and suspicions in relation to Raphaela began to mount, coming from the religious that formed the nucleus of the institute’s government, to the point where she was relegated to complete isolation. All those who from the beginning had supported her, now abandoned her and blamed her for whatever evil might befall the congregation. Mother Mary of the Sacred Heart had no choice but to relinquish the post of Superior General into the hands of her sister Dolores.

How could the renunciation of Raphaela be explained to the religious who considered her the holiest member of the institute? Word began to spread in all locations of the institute that she no longer had the mental capacity to govern and that her lucidity was diminishing…

Sent to the house in Rome, Raphaela Mary watched the days pass in dire solitude. Isolation, doubts, silence, futility: this would be her lot for more than thirty years. Until that time, her life had been spent in continual work, in apostolic activity of every kind. From Rome, she would follow the development of her foundation, “only detecting by clues, by small signs, its problems, its sorrows and its joys.”11

The Cross of abandonment and oblivion

Raphaela was aware that “never has one who obeyed been condemned,”12 and she resolved to untiringly do everything within her grasp. “If I become a saint, I will do more for the congregation, for the sisters and for my neighbour than if I were dedicated to the most productive offices.”13

Raphaela no longer had any authority in the institute. The elder religious hid her under a veil of silence, and from them she only received humiliations and ingratitude. Those who had followed her with such enthusiasm since the “flight” from Cordoba now became the executioners of her crucifixion.

Accepting the bitter chalice of abandonment that the Lord offered her, Raphaela became anonymous within the work she had founded. “Without anyone finding it strange, they would see the now elderly Mother helping a recently arrived coadjutor postulant to set the tables. […] Increasingly unknown, the time came when even those living in the congregation did not know that it was founded by her.”14

Great trials tormented her pure heart, as she writes: “My life was always a battle, but for the last two years the sufferings have been so extraordinary that only God’s omnipotence, which miraculously supported me at every moment, prevented my body from falling to the ground. […] My entire being is in constant anguish and abandonment, and I am foreseeing that this will last for a very long time. Do I think, for this reason, that God has abandoned me? No!”15

Humility and service until the end

Amid so many sufferings, Raphaela stood out in the community for her constant readiness to help others, rescuing them from any plight. Despite her advanced age, she was the servant of all so that her Lord would be fully served. Any affliction seemed to her a consolation, for she knew that the coming glory would far surpass any misfortune.

Whence did she draw the necessary strength to endure the abandonment of those closest to her, as well as being apparently forsaken by Providence? Many were the hours she spent before the Blessed Sacrament! With the passing of the years, she learned to remain constantly in prayer, transforming the most servile tasks into the highest contemplation. Before the Infinite God, centre of her love, she placed her life, her anguish, her sacrifices. In offering Him her duties, every work was light and every suffering agreeable.

Due to the continual hours spent kneeling in adoration before the Blessed Eucharist, she eventually contracted an ailment in her right knee that, over time, would lead to her death. Even when suffering acute pain, she never allowed the illness to prevent her from serving everyone. She was more concerned with the problems of her neighbour than her own.

On January 6, 1925, after terrible sufferings heroically endured, she piously expired in the same way in which she had lived: humble both in consolation and in abandonment.

Only three people attended her burial… But that soul enamoured of God attained the plenitude of the virtues amid silence, suffering and the most complete obscurity. From Heaven she would participate in the growth of her work, a fruit of the sacrifice of her life. ◊

Notes

1 YAÑEZ, ACI, Inmaculada. Amar siempre. Rafaela María Porras Ayllón. Madrid: BAC, 1985, p.9.

2 Idem, p.10.

3 Idem, p.17.

4 Idem, p.23.

5 Idem, p.28.

6 Idem, ibidem.

7 SÁNCHEZ, ACI, Evelia. Santa Rafaela María del Sagrado Corazón. In: ECHEVERRÍA, Lamberto; LLORCA, SJ, Bernardino; REPETTO BETES, José Luis (Org.). Año Cristiano. Madrid: BAC, 2002, v.I, p.158.

8 Idem, ibidem.

9 Idem, ibidem.

10 DESCALZO, José Luis Martín. Prólogo. In: YAÑEZ, ACI, Inmaculada (Ed.). Santa Rafaela María del Sagrado Corazón. Palabras a Dios y a los hombres. Cartas y apuntes espirituales. Madrid: Congregación de las Esclavas del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús, 1989, p.19.

11 YAÑEZ, Amar siempre. Rafaela María Porras Ayllón, op. cit., p.67.

12 ST. RAPHAELA MARY OF THE SACRED HEART. Carta n.116, a la M. María de la Paz. Madrid, septiembre de 1883. In: YAÑEZ, Santa Rafaela María del Sagrado Corazón. Palabras a Dios y a los hombres. Cartas y apuntes espirituales, op. cit., p.144.

13 SÁNCHEZ, op. cit., p.160.

14 Idem, p.161.

15 ST. RAPHAELA MARY OF THE SACRED HEART. Carta n.380, al P. Isidro Hidalgo, SJ, Roma, 29/9/1892. In: YAÑEZ, Santa Rafaela María del Sagrado Corazón. Palabras a Dios y a los hombres. Cartas y apuntes espirituales, op. cit., p.420.