There is a vast bibliography on the subject of suffering. Rivers of ink, both sacred and profane, have flowed alongside the rivers of blood, sweat and tears shed by the human race since Adam and Eve left Earthly Paradise. Discovering the origin of the universe, where we came from and where we are going, has always been a huge question. But recognizing the origin and purpose of our suffering and learning to bear it seems equally important.

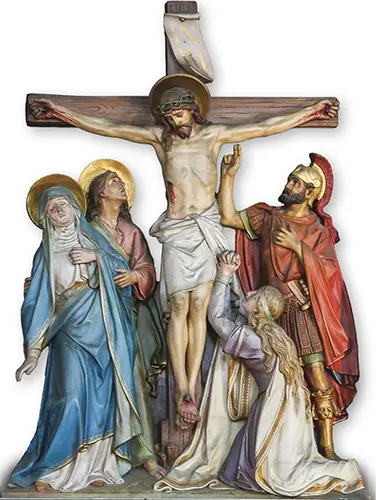

The Catholic notion of suffering is incomparable: it was taught by the crucified God Himself, who became sin for us

The Catholic notion of suffering is incomparable: it was taught by the crucified God Himself, who became sin for us (cf. 2 Cor 5:21) – this is the most obvious origin of suffering, the punishment for original sin – and who revealed to us its supreme purpose: “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (Jn 15:13).

Distilling the most precious nectar from sacred doctrine and exposing it in the light of his gift of wisdom, Dr. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira coined the term “sufferative” to describe the disposition of the human soul faced with this prospect.

Based on extracts from various talks he gave between 1960 and 1990, we invite the reader to consider, in an overview, some of his explanations in this regard.

The “sufferative” capacity

A deeper reflection on the subject began when Dr. Plinio was just twelve years old, as he observed how suffering had a remarkably stabilizing and balancing effect on the soul of his mother, Dona Lucilia.

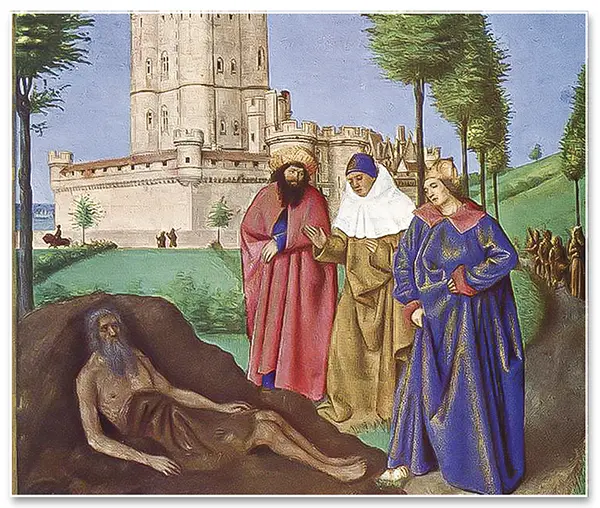

But it was only when he took special note of the tragic biblical figure of holy Job, while still in his teens, that he coined the expression.1

It was considering the tragic figure of Job that Dr. Plinio created the expression “sufferative”, which describes the human capacity for suffering

The “sufferative” is therefore “a certain limit in man’s nature, beyond which God will ask nothing further, for He has circumscribed him to this, and if He were to demand more, He would tear His creature apart. […] It was this limit that Satan could not transgress, otherwise Job would die. It was this limit that God also respected…”2 In this sense, Job’s “sufferative” – or his capacity to suffer – was taken to the end; it reached its peak.

Now, “from a certain standpoint, every man, in relation to his own ‘sufferative’ faculty, is a Job. And when it comes to an upright and good man, God makes him suffer to almost the full extent of his ‘sufferative’.”3

Therefore, He sets such limits so that people can collaborate in the plan of salvation. Of some He says: “Have you noticed my servant Job?” (cf. Job 2:3). And he uses their merits in union with the Most Precious Blood of His Divine Son. Dr. Plinio gives an example: “When in a given country the souls called to this donation give everything, an incense of a pleasing odour rises from that country to the throne of the Most High, which inclines Him to do what they desire.”4 There is then “an action on the part of men to deter or advance the divine plan in history, which depends very much on human action… God as it were allows Himself to be conditioned by men.”5

A “psychological fraud”: the myth of life without suffering

The “sufferative”, however, is not merely a passive ability, as it might seem at first glance. All people – even those most averse to pain – not only carry this capacity for suffering in their souls, but they also have, because of it, a real need to suffer, which is co-natural to the human condition.

As Dr. Plinio explains, it is a myth to think that it is possible, on this earth, to organize a life without suffering. This myth is based on ignorance of a fundamental fact, the centre of human psychology: “In every human soul, by virtue of original sin, there is a kind of ‘sufferative’ […]. That is to say, a sort of need-capacity to suffer which, when it is not exhausted by actual suffering, causes greater frustration and makes us suffer more than would suffering itself. So that, in the final analysis, the least unpleasant way to lead one’s life is still to suffer.”6

Such observations seem to shed light on a hundred disorders that afflict contemporary man, so unaccustomed to accepting pain as an unavoidable companion of his earthly existence.

“I think,” continues Dr. Plinio, “that one of the profound reasons for modern disorders is not so much that people do not suffer; because they do suffer, and suffer a great deal. It is that they end up forming the idea in their minds that it is possible to lead a life without suffering. And then they begin a series of psychological deceptions in order to live as if they were not suffering. Thus a regime of eternal deception is established, a regime of psychological falsification, the effect of which is necessarily a mental imbalance,” because “the happiness of life consists in suffering with measure, number, and weight, in view of a certain end and in undergoing the good suffering that this end justifies.”7

And Dr. Plinio concludes: “Do you want a life of hell? I will give you the recipe right away: avoid suffering.”8

Suffering is inherent to the human condition

The descriptions in Genesis portray man in Paradise free from any form of pain. No scratches, insomnia or colds threatened him. Not even death frightened him, because the gifts of impassibility and immortality gave Adam and Eve a truly excellent nature.

But there was suffering, according to Dr. Plinio: the state of trial itself.

Of course, the condition of suffering was greatly increased after original sin, but regardless of this, man “was created in a state of trial and it is normal that, as a result, there should be something in the depths of his being that makes him feel obscurely that, if he is not tested, he has not lived. And because of this, he both abhors the trial and feels the need for it.”9

Dr. Plinio then asks whether Adam and Eve, and even the Angels themselves, were aware of the imminence of the trial. And he answers that, if they had known about it, “they would have wanted the time to come, so that in the pain of the trial – it would not be a trial if there were no pain to be accepted – they could reach the perfection of order required of them to be what they should be.”10 For Dr. Plinio,11 the trial of the Angels, for example, was essential for the angelic spirits to acquire the degree of perfection for which they had been created.

The reasons provided above would be enough to demonstrate the mistake, unfortunately so widespread today, of an education given outside the perspective of suffering. How many parents – to mention only family life – could avoid immense frustration for their children if they did not foster false illusions about the difficulties and hardships that are inevitable in human existence.

Love and the cross

Since we are heirs of original sin and bearers of actual guilt, our “sufferative”– to now freely use the term coined by Dr. Plinio – has an expiatory and reparatory character. But there is yet another aspect that needs to be emphasized.

Those who love the good suffer. And they suffer “as a generous, disinterested proof of love for God, because there is no manifestation of love without suffering.”12

We know, then, that the Divine Redeemer’s atoning sufferings – the greatest proof of love He could offer us – served to redeem all of humanity. They therefore had a reparatory character par excellence and signified the culmination of God’s love, an incomprehensible, disproportionate, immeasurable love for His poor creatures.

“When we love someone very much, we take a virtuous kind of pleasure in sacrificing for their benefit something that means a lot to us”

This is very much the “sacrificial character” of suffering, symbolized in the burnt offerings of the Old Law: “When we love someone very much, we take a kind of pleasure – an upright, virtuous pleasure, consistent with the good order of things – in sacrificing for their benefit something that means a lot to us.”13

Who does not admire the conduct of a family man who works hard to provide for his children and his wife? And who is not moved by the sight of a good mother who sacrifices her sleep at the bedside of a sick child, completely forgetful of herself and willing to make any sacrifice for the sake of her little one? Such examples help us to realize that even the ordinary events of everyday life can be adorned with notes of nobility and heroism, as long as we know how to lovingly embrace the cross that God places on our shoulders.

How much and how to suffer?

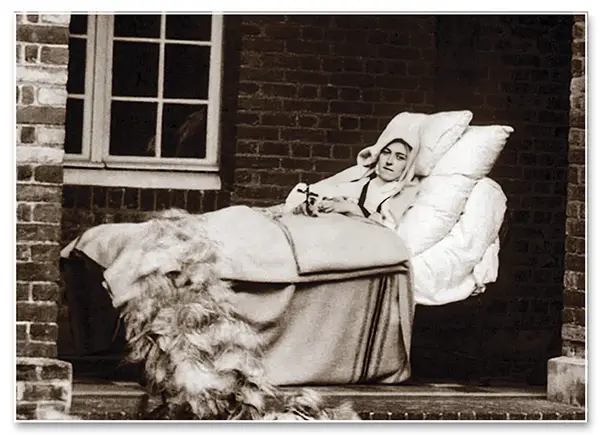

If running away from suffering is a grave mistake, so is running after it without a measure of prudence. As we seek to fulfil our duties as parents, children, religious, teachers, students, spouses – whatever our state – the Lord will send us suffering in the proportion necessary for our sanctification. The God who wounds, cares for the wound (cf. Job 5:18). In other words: He sends the illness and prepares the sick bed.

To suffer with a Catholic spirit is to have a trusting heart and know how to rejoice in consolations, like true children of God. Family life, the licit pleasures of the senses, the beauty of nature and the spiritual attractions of art are all smiles from the Creator to comfort souls in this vale of tears.

Above all, although God’s specific designs are mysterious to us, by understanding the higher reasons for everything that happens on our earthly journey, we will end up seeing our sorrows as a source of happiness.

There is great wisdom in the acceptance of suffering. And we are not referring mainly to the big sufferings. Restricting what one eats, not wanting to be admired, silently accepting small humiliations, not always seeking the greatest comfort, making certain physical efforts that are not strictly necessary… how much we would grow if we made good use of these occasions to mortify our egoism!

However, many run away from the beneficial suffering of a little meditation, of freeing themselves from the rush to get a few minutes of silence that quickly become so delightful. Others escape pain through a “systematic optimism” and live as if evil and error did not exist, their lack of insight and lucidity reaching the point of what Dr. Plinio did not hesitate to call “mental obesity”.14 Still others, at home or at school, fail in the sacred mission of teaching because they follow the principle that one should never cause others to suffer, and they thereby abandon salutary discipline and exigency…

Ask for the grace to suffer

Suffering well confers nobility, orders the mind, gives meaning to life, repairs our offences, restores innocence and allows us to show our love

In short, suffering well confers nobility and assures oxygen for virtue, orders the mind and inspires good temper and humour, gives meaning to life, repairs our offences, restores innocence, allows us to show our love, obtains graces for the Mystical Body of Christ and moves the history of humanity.

Let us flee from this great modern sham: the myth of earthly happiness free from sorrow and struggle.

And we conclude with this beautiful reflection by Dr. Plinio: “If someone wants to have an idea of how much God loves him, he should measure it by the amount of suffering he receives. And if he receives little, he should say to Our Lady: ‘My Mother, I am insignificant, I am feeble, but in the measure of my weakness, do not forget me. Because who knows what accounts I will have to render to thy Divine Son, if I live forever without suffering.’”15 ◊

Notes

1 In a conference on May 23, 1964, Dr. Plinio justified the choice of the term “sufferative” because of its phonetic similarity to the word “cogitative”, the power of the soul dealt with by St. Thomas Aquinas in the context of what is now considered his knowledge theory, responsible for grasping non-sensible objects, such as the useful or the harmful.

2 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Talk. São Paulo, 30/4/1995.

3 Idem, ibidem.

4 Idem, ibidem.

5 Idem, ibidem.

6 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Talk. São Paulo, 23/5/1964.

7 Idem, ibidem.

8 Idem, ibidem.

9 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Talk. São Paulo, 26/2/1986.

10 Idem, ibidem.

11 Cf. CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Talk. São Paulo, 30/10/1974.

12 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Talk. São Paulo, 23/5/1964.

13 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Conference. São Paulo, 3/7/1982.

14 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Talk. São Paulo, 23/5/1964.

15 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Conference. São Paulo, 21/1/1970.