Impostor: someone who lives in a dream world, believing himself to be something he is not, with the candour of a child and the malice of a demon. The impostor wants his word to be believed and even his authority to be acknowledged. In him, hypocrisy masks the truth, dissimulation camouflages his actions, and cunning attempts to give the appearance of goodness to evil deeds.

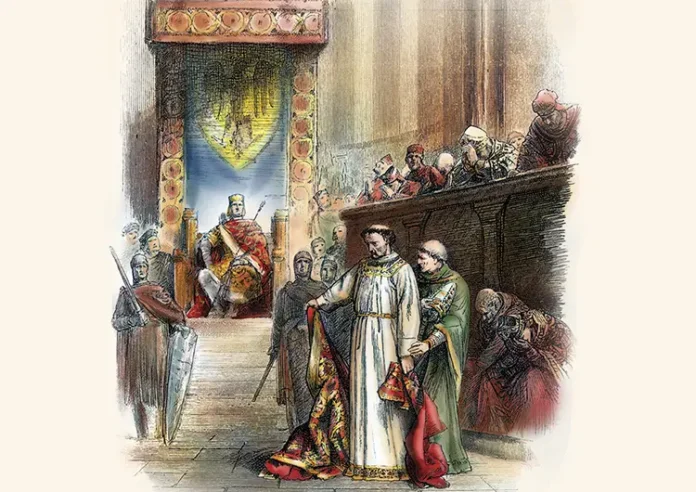

In the succession of the supreme hierarchs of the world – the Roman Pontiffs – some personages presumed to attract the attention of their epoch. Such impostors, dressed in white, passed into posterity with the black title of antipopes: those who usurped the title and functions of the Bishop of Rome, in opposition to the legitimate Pope.

An antipope… who is a saint?

The case of St. Hippolytus, the first antipope, is particularly curious. Coming from Alexandria, in the year 170 he arrived in the Eternal City, where he was ordained by Pope Victor I. The new priest was a man who found it difficult to bow his head. Could a great theologian submit to the unsophisticated Bishops of Rome? And how would he accept the excessive mercy they showed to penitents?

Some personages, dressed in white, passed into posterity with the black title of antipopes: those who had usurped the title of Bishop of Rome

When, in 217, Callistus was chosen as Peter’s successor, Hippolytus’ supporters separated from the Church and elected him invalidly. Almost twenty years passed until the persecution of Maximinus ravaged the Church and several dignitaries were expatriated.

According to pious tradition, while in exile, the antipope Hippolytus bowed before Pope Pontian, then reigning, recognizing his supremacy. Shortly afterwards, both preferred death to apostasy. And, with martyrdom uniting those whom life had separated, Hippolytus was added to the roll of the blessed.1

Between Peter and Caesar

Of the great temptations that can assail a man, one of the most dangerous is to consider himself a miniature of God. The Roman emperors were not exempt from this danger. In fact, when they saw religion as an opportunity to assert their powers, they defied the Saviour’s command: “Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s” (Mt 22:21). And it is not Caesar’s place to elect Popes.

Emperor Constantius, in the middle of the fourth century, exiled Pope Liberius to Thrace after theological disagreements. Now, when an imperial official was exiled, he automatically lost his positions. Considering Liberius’ functions terminated, Constantius decided that the deacon Felix should succeed him.

The people of Rome did not accept the antipope and staged a revolt. In 365, faced with the untenable situation, the emperor sought a compromise: Felix would share the papacy with Liberius in a kind of diarchy.2 Such concessions, however, have the rare quality of pleasing neither side…

Forced to withdraw, Felix would end his days in the suburbs of Rome, still exercising episcopal functions. His comedy, however, taught history a serious lesson: Catholics distinguish the voice of the shepherd from that of the mercenary.

The persuasive force of arms

Since the Bishop of Rome was an authentic sovereign prince with temporal powers, there were also attempts to dominate the Apostolic See for its secular value.

No shortage of men attempted to dominate the Apostolic See for its secular value and not a few hoped to buy the Throne of Simon Peter

This was the case when Paul I died in the summer of 767, when the climate was heated in every sense. Two parties had formed around his deathbed: that of Duke Toto of Nepi, supported by the army; and that of Canon Christophorus, supported by the Roman nobility. Using the persuasion of arms, Toto seized power and made his brother Constantine, a layman, the invalid successor to Paul I. Christophorus, however, rushed to beg for the help of King Desiderius and managed to impose order on the city. The antipope Constantine was blinded and, after a new attempt to consecrate an antipope, the legitimate election of Stephen III occurred.

“There are evils that come for good.” After a turbulent election, the new Pontiff convened a synod in 769 to deliberate, among other issues, on papal elections. From then on, only the clergy would have the right to vote, and only cardinals would be candidates.

How much does it cost to be Pope?

The case of Benedict IX, whose name appears three times on the list of Popes, is exceptional. Elected in 1032, he was forced to flee the revolutions that shook Rome in 1044, resulting in his deposition and the election of Sylvester III as Pontiff. Less than a year later, he returned to the papal throne… but only briefly, as after two months he sold the position for fifteen hundred pounds of gold.3

What a sad price Benedict placed on the Throne of Simon Peter! In fact, he proved to be an ally of another Simon – the Magician – who, in the early days of the Church, sought to buy divine power for money (cf. Acts 8:18-23), thus inaugurating the shameful list of men who would engage in the commerce of spiritual goods.

Despite such egregious simony, Benedict IX was re-elected in November 1047. Tired, however, of such a turbulent existence, he resigned definitively the following year, not without leaving the mark of his bad example on history. From thence arose a long dispute between supporters of the German emperors and defenders of the Roman clergy. Capitalizing on the conflict, ten antipopes appeared over the course of a century.

In order to prevent a recurrence of such disasters and to reaffirm that the Church is in the world but not of the world, Nicholas II issued a decree on April 13, 1059 concerning the election of the Pope.4 Although the emperor was consecrated by the Pope, he could not appoint the Roman Pontiff.

Everything seemed to be resolved. But man is made of clay.

Three Popes and one Church?

The unrest that followed the death of Gregory XI in 1378 was the first symptom of the acute illness that had infected the Papacy in the decadence of the Middle Ages. After seventy years of Pontiffs exiled in Avignon, the world was divided between those who aspired to a Roman solution and those who longed for a French successor.

The one elected, however, was an Italian, Urban VI, whose exaggerated stance soon served as a pretext for the election of another Cardinal, the Spaniard Pedro de Luna, who took the name Benedict XIII.

Two were elected… Who was the Pope? To solve the problem, the voluntary resignation of both was required. But neither intended to leave his position. They tried to resolve the case in Pisa, where, in 1409, an illegitimate council elected Alexander V as Pope. This only complicated the situation further: instead of two, there were now three would-be pontiffs.

Even if enemy hands seem to seize the helm of Peter’s Barque, the wicked will die and the Church will continue to traverse the centuries

Seeking a final solution, a council was convened in Constance. The antipope of Pisa was deposed. The true Pontiff renounced the Papacy. And Benedict XIII, eternally obstinate, would be dethroned. In November 1417, the new Pope was elected: Martin V.

What do the antipopes teach us?

The evil of the antipopes seemed mortally wounded. In fact, Felix V, who seems to have been the last of these impostors recorded by history, would reconcile with the Church in 1449. But was he really the last antipope? We will only be sure at the end of the world…

The papal tiara will always be coveted by ambitious men, avid for all crowns, of whatever kind. The demonic powers, as well, aided by their earthly cohorts, will always seek to seize for themselves the keys of Peter, those keys that can open Heaven and lock the eternal abyss. It would be their greatest triumph… if it were not for the divine promise that the Church will prevail over the gates of hell (cf. Mt 16:18-19).

The more than forty antipopes who have appeared throughout these two thousand years of Christianity – and all others who may yet attempt to usurp the Holy See – have left us, or will leave us, at least one edifying lesson: even if enemy hands seem to steal the helm of Peter’s immortal Barque, the jaws of hell will not engulf it. The impostor will die, and the Church will continue to sail the seas of the centuries. ◊

Notes

1 Cf. PAREDES, Javier (Dir.). Diccionario de los Papas y concilios. Barcelona: Ariel, 1998, p.21.

2 Cf. Idem, p.36.

3 Cf. Idem, p.153.

4 Cf. DANIEL-ROPS, Henri. A Igreja das catedrais e das cruzadas. São Paulo: Quadrante, 1993, p.198.