Even beyond Dona Lucilia’s virtuous aspirations to the lofty and sublime was the determination to fulfil God’s will, even if this meant relinquishing some of her good inclinations.

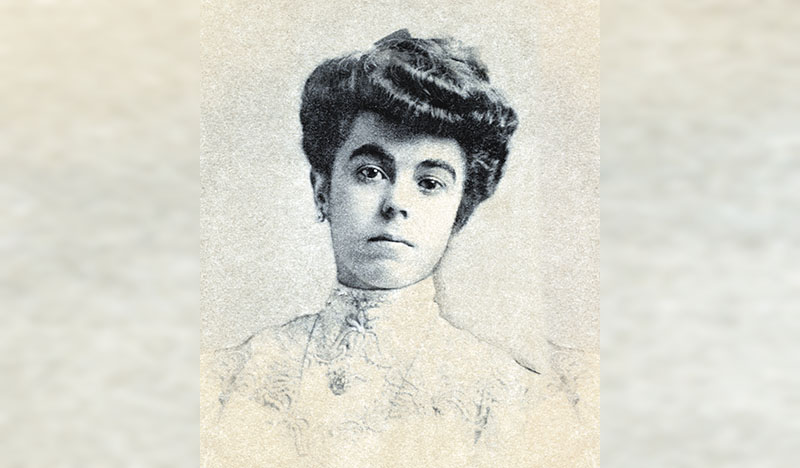

As she approached the age of thirty, during long hours of quiet contemplation mingled with vocal prayer, the desire for the religious life became increasingly defined in Lucilia’s soul. However, even beyond her virtuous aspirations to the lofty and sublime was the determination to fulfil God’s will, even if this meant relinquishing some of her good inclinations.

She was ready to follow the voice of the Holy Spirit at all moments, cost what it may, convinced that He often made His wishes known through the orders or counsels of her dear father, Dr. Antônio Ribeiro dos Santos.

Docility to the designs of Providence

One evening, with characteristic fatherliness, Dr. Antônio broached the delicate topic of matrimony with his daughter. He reflected that the years were passing by, threatening to leave her a spinster around whom nephews and nieces would play.

Of course, as a good father, Dr. Antônio did not wish to compel Lucilia to make a decision about marriage. But he told his daughter that a friend of his, Dr. João Procópio de Carvalho, had presented a young lawyer to him, Dr. João Paulo Corrêa de Oliveira, a descendant of an illustrious family from the state of Pernambuco, very refined and intelligent. For these reasons, Dr. Antônio considered him a suitable match, but would leave the final word with her.

Dona Lucilia listened to her father’s suggestion with her customary mild and amiable expression – a sign that the stability of her temperance had already reached full bloom.

If the will of Providence was being revealed in this way, why not be glad? Her future husband must be a good man, since he was recommended by Dr. Antônio. What else was needed for her consent? But always measured and prudent, she asked her father for some time to think it over. Only after much prayer and reflection did she consent to having the worthy and genial lawyer presented to her, and they became engaged.

Lucilia was not mistaken when she discerned in her father’s words an indication of God’s designs for her. For she was, in fact, called to exercise the irreplaceable role of a good mother for Dr. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, a man raised up by God to mark the twentieth century with his virtue and action in favour of the Holy Catholic Church and Christian Civilization.

Wedding pomp

July 15, 1906, was a significant date in São Paulo’s social chronicles on account of the brilliant event reported the next day in the “Correio Paulistano.”

“Yesterday, in this capital, the marriage between Miss Lucilia Ribeiro dos Santos, beloved daughter of Dr. Antônio Ribeiro dos Santos, and distinguished lawyer Dr. João Paulo Corrêa de Oliveira took place. […]

“The very well-attended religious ceremony was celebrated at 8:30 in the evening in the chapel of the Diocesan Seminary. The Venerable Archdeacon Francisco de Paula Rodrigues, administrator of the diocese, proffered a beautiful prayer imploring blessings for the couple’s future.”

The numerous guests from the highest society flowing into the church piqued the curiosity of passers-by, who soon formed a lively crowd in front of it.

Immediately following the ceremony these spectators watched with mounting fascination as a winding cortège of carriages and automobiles proceeded toward the Ribeiro dos Santos residence. Leading the way, the newlyweds’ car attracted the most attention, tastefully adorned and upholstered in silk.

The long-awaited encounter with the Eucharistic Jesus

Before the pontificate of St. Pius X at the beginning of the twentieth century, the privilege of First Holy Communion had not yet been extended to children and adolescents. But this was not the only reason that prevented Lucilia from receiving this Sacrament until close to her marriage. The Brazilian population of the time was mostly Catholic and would attend all religious events, yet would rarely receive the Sacraments. This contradictory attitude was partly the result of a vicious anti-clerical campaign – which the censurable conduct of a certain number of ecclesiastics only served to foment.

This brought with it regrettable misunderstandings between the clergy and faithful, and favoured the spreading of appalling rumours such as the insinuation that some priests used the confessional to make shameful propositions to penitents. Within this sad climate, it may be understood why the heads of many households barred their daughters and wives from Confession. Dr. Antônio thought he was acting correctly by taking such a position.

For a soul ardently devoted to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Communion would have been the natural apex to intimacy with the Divine Saviour. The long delay in receiving this Sacrament was a heavy ordeal for young Lucilia. Although she never allowed this to diminish her high regard for her father, she could not hide her respectful incomprehension with his inflexible attitude, but to no avail.

Her marriage finally allowed her to fulfil her long-awaited desire to receive Our Lord in the Eucharist. As the wedding approached, Dr. Antônio said to his future son-in-law:

“Dr. João Paulo, because of the state of the clergy, I have never permitted Lucilia to go to Confession or, as a result, to receive Communion, although she has truly desired this. Since the situation is improving, I am more inclined to allow it, but this is in fact your decision. If you agree, she will confess and receive Communion now, before the wedding.”

Dr. João Paulo looked at his fiancée to see what she wished. With customary graciousness, she said that she would like very much to receive Communion regularly. With this agreement between the two of them, Lucilia was able to confess and receive First Holy Communion, on the eve of her wedding (July 14, 1906), in her beloved chapel of Luz Convent. By this means, her soul gained added strength to face the uncertainties of her new state of life. ◊

Taken, with slight adaptations, from:

Dona Lucilia. Città del Vaticano-Nobleton:

LEV; Heralds of the Gospel, 2013, p.97-101