The universe holds countless mysteries that make the human heart wonder. From the largest stars to the tiniest grains of sand, everything contains mysteries and complexities so harmonious that there is no way to avoid the questions: “How is it possible for this to exist in this way? Is there a mind behind such order?” The desire to know the truth leads us, then, to delve into the enigmas that each part of the universe encloses.

However, there are many scholars who use their knowledge to try to deny the existence of the Creator and who seek to unravel such enigmas solely through secondary causes, doing everything possible to avoid the ultimate and definitive conclusion: at the origin of everything is God.

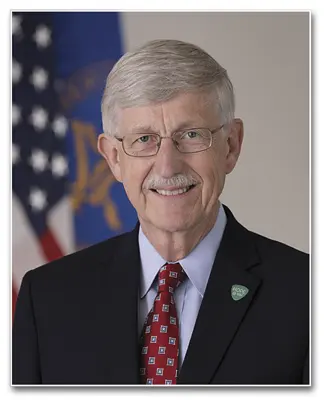

But fortunately, they do not represent the totality of scientists. Among those who break the rule, Francis Collins stands out, a great exponent in biochemistry and director of the international study commission Human Genome Project. Not content with having faith, he strives to proclaim it at the top of his lungs. He is the author of works that seek to base Christianity on data obtained through his studies and personal experience.

Some might think this is just another Catholic who became a scientist, and used his knowledge to consolidate his faith; in reality, however, his story is quite different.

Beginnings unrelated to Faith

Born in 1950, Francis Collins had a childhood not unlike that of other young Americans of his time.

A farm in Virginia, and an environment devoid of religion was the setting for his birth and childhood. From his early youth, he showed a fascination for science. He was enchanted by the possibility of understanding the atoms and molecules that constitute beings and had no other project for his life than to dedicate it to the study of the universe through Chemistry. But Divine Providence assigned him a role far superior to what he was able to imagine.

At the age of sixteen, he entered the University of Virginia to study his favourite subject and pursue a scientific career. As a young freshman, he was enthusiastic about the burning issues that ricocheted among the students, which, naturally, also converged on the problem of God’s existence.

Having a very limited spirituality, he was easily swept away by the arguments of atheist classmates.

At that point in his life, he became convinced that, although religions had played a significant role in the formation of cultures, they did not actually uphold a fundamental truth.

For this reason, he began to declare himself an agnostic, a term used to indicate someone who simply does not know whether God exists or not.

Thus, a series of prejudices regarding Christianity gradually formed in his mind.

From agnosticism to atheism

After graduating in Chemistry, he earned a doctorate in Physical Chemistry from Yale University when he was just twenty-two years of age. Francis Collins became increasingly certain that the universe could be explained solely by means of equations and the principles of physics.

Thus, he gradually abandoned his agnostic position to embark on the path of staunch atheism: “I felt quite comfortable challenging the spiritual beliefs of anyone who mentioned them in my presence, and discounted such perspectives as sentimentality and outmoded superstition”.1

However, his militant stance towards religion was not simply the result of reasoning. Collins confesses that atheism, at its core, was the result of a justification for his moral actions, an attitude he later described as “wilful blindness.” Belief in God demanded a change of customs that he was unwilling to accept.

After completing his doctoral studies, Francis realized that his studies and theses on thermodynamics – an area which, in his view, no longer offered significant new advancements – would lead him down a path he dreaded: that of a university professor dedicated solely to lecturing to bored students. This fear prompted him to enrol in a Biochemistry course, a field with more potential for development.

Suffering opens his eyes

Shortly before completing his doctorate, he applied to be admitted to the Medical College of North Carolina.

In his third year of study, he had the opportunity to come into contact with the reality of a hospital and gain intense experiences in interacting with patients. There, he took the first step towards a turning point in his life.

When the sick faced suffering and the imminence of death, that reserve that normally prevents strangers from exchanging intimate feelings often disappeared. Medical students ended up becoming the most assiduous confidants – or even faithful friends – of the sick and dying, who no longer had any reason to hide their thoughts about life.

The young intern Francis Collins was amazed to see the spirituality of most of the sick.

He witnessed moments in which faith provided them with a definitive serenity, despite their suffering, and he was surprised that none of his patients rebelled against God or demanded that their families cease all their “talk” about supernatural power and divine benevolence. These observations led him to conclude that, if faith was nothing more than a psychological crutch, it might at least be quite a powerful one.

This was his first step towards definitive conversion.

A scientist who does not consider the data?

Thoughts of this kind began to dominate his mind, leaving him in an awkward situation.

This confusion reached its peak when he came into contact with an elderly lady who was suffering from acute pain with no prospect of relief. She asked him what he believed in. Collins felt himself blush at the question and stammered, embarrassed: “I’m not really sure.”

Those brief seconds of conversation tormented him for several days. He realized that he had never seriously considered the evidence for and against belief: “Did I not consider myself a scientist? Does a scientist draw conclusions without considering the data?”2

Dr. Francis Collins

Suddenly, all his arguments for denying the existence of God seemed too weak in the face of the religious convictions of a lady who had probably never studied her belief in depth, but who possessed the most important thing of all: faith.

From then on, Francis Collins had no other interest than to analyse the various creeds and seek the one that possessed the greatest plausibility. He began reading short summaries of all sorts of religions, but none of them seemed coherent to him.

In search of the plausibility of the Faith

Collins found no better way to overcome this difficulty than to consult a Protestant pastor who lived next door to him. He presented his situation and asked if there was any reasonableness in the Christian belief. His interlocutor took a book from his personal library and handed it to him, recommending that he read it.

It was Mere Christianity, a book by an Oxford professor, Clive Staple Lewis, dedicated to presenting very convincing arguments in favour of Christianity. It is curious to note that, despite being written by an Anglican, the book ended up leading Francis Collins into the bosom of the Catholic Church. Undoubtedly, God writes straight on crooked lines…

Mere Christianity truly caught Collins’ attention because of its argument concerning the moral law. Indeed, Lewis affirms – in complete agreement with Catholic doctrine – that it is inscribed in the soul of all men.

This law is evoked in diverse ways, every day, without the one who does so stopping to analyse the basis of their argument. From a child declaring that it is “not fair” to distribute different amounts of ice cream at a birthday party, to two doctors arguing about the legality of conducting research with embryonic stem cells – one opposing it because it violates the sanctity of human life, and the other defending it because the potential to alleviate human suffering constitutes a reasonable justification – all of them will have to resort to a standard of conduct, even if implicitly.

This standard is the moral law, which can also be called “the law of correct behaviour,” and it is a matter of knowing whether a given action approaches or deviates from the requirements of that law.

Someone might object that this ethics is the product of certain cultural traditions.

Lewis, however, shows how asserting this would be a “resounding lie. If a man were to go into a library and spend a few days with the Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics he will soon discover the massive unanimity of the practical reason in man. From the Babylon Hymn to Samos, from the Law of Manu, the Book of the Dead, the Analects, the Stoics, the Platonists, from Australian aborigines and Redskins, he will collect the same triumphantly monotonous denunciations of oppression, murder, treachery and falsehood, the same injunctions of kindness to the aged, the young, and the weak, of almsgiving and impartiality and honesty”.3

Charity: how to explain it?

However, moral law also has another dimension that left Francis Collins amazed: altruism, the generosity that emerges in the human soul when confronted with a situation that requires helping others, being willing to sacrifice oneself solely for the benefit of others.

It is the so-called agape, which does not seek reciprocation.

Lewis argues, with solid arguments, that altruism represents a great challenge for evolutionary atheists, since they have not yet been able to explain how this impulse could have arisen in human beings through exclusively natural evolutionary means.

There is no convincing parallel to agape in any irrational being.

Now, if natural law does not come from either cultural conditions or evolution, how can it be explained? Lewis answers:

“If there was a controlling power outside the universe, it could not show itself to us as one of the facts inside the universe – no more than the architect of a house could actually be a wall or staircase or fireplace in that house.

The only way in which we could expect it to show itself would be inside ourselves as an influence or a command that urges us to behave in a certain way. And that is just what we do find inside ourselves. Surely this ought to arouse our suspicions?”4

Atheism no longer made sense.

The then twenty-six-year-old doctor was completely astonished by the reasonableness that Faith offered him, and how these realities are obscured by the experience of the contemporary world.

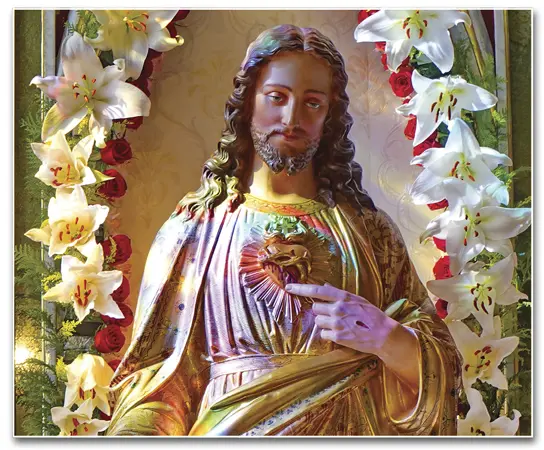

Sacred Heart of Jesus – Church of Our Lady of Carmel, Caieiras (Brazil)

The moral law reflected the resplendent rays of the Creator and demanded a series of considerations regarding God.

Agnosticism, which once seemed to him a safe haven, revealed itself as an undeniable excuse for wrongdoing.

After a long conversion process, in which other objections were also overcome, Francis Collins ended up adhering to the Catholic Religion, because he realized that the God of the Christians was the one who best personified the reasons he found to believe in a divinity.

Hope for others

The account of the conversion of someone who is still alive, and who dedicated his life to the study of human DNA, constitutes further proof of how religion is not limited to a belief to which one adheres as learned from one’s parents, but a reasonable fact, even from a scientific point of view.

The name Francis Collins brings hope for the conversion of those men whose “faith” in preconceived notions against religion is their greatest barrier to belief in God. ◊

Notes

1 COLLINS, Francis. The Language of God. A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief. New York: Free Press, 2007, p.16.

2 Idem, p.20.

3 LEWIS, Clive Staple. Christian Reflections. Grand Rapid/Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans, 1967, p.95-96.

4 LEWIS, Clive Staple. Mere Christianity. New York: HarperCollins, [s.d.], p.24 [e-book].