To be Catholic, one must be a hero. But how often, to be a hero, one must be Catholic.

The first principle, every Catholic discovers with the impact of their first spiritual battles. To prove the second, let us refer to some events that occurred in the first months of the First World War,11914-1918.

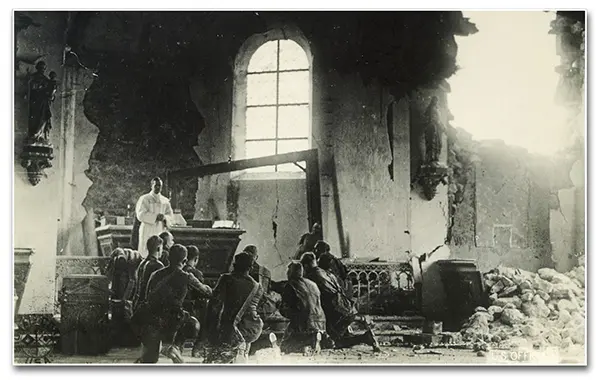

The church in ruins…

The colonel’s sabre, in a dry and quick stroke, cuts through the morning mist, still tinted by a sun rising over a devastated field, a cemetery of men and buildings. The platoon stops its march at the silent order that gleams on the officer’s blade.

“A priest of good will!” the commander calls.

Father Duroy steps out of the formation:

“Present!”

To the left of the complex, a church remained standing, even after the relentless bombardments of the previous day. The French regiment and the church were, on that battlefield in 1914, the only ones that had survived the German artillery.

The officer’s voice rises again amid the ruins:

“Who wishes to attend Mass?”

All arms rise. Souls mobilize.

Suddenly, a crash! Some howitzer shells fall a short distance away. Their bursting shrapnel claims two lives and leaves nine wounded. It is the call for the Holy Sacrifice. The regiment storms the church.

Mass begins, the harmonium resounds, and the chants rise. The church trembles. Not only from the voices of the twelve hundred soldiers, baptized not only by the regenerating waters, but by the fire of the previous day and the projectiles falling at an ever-shrinking distance. But the infantry does not tremble: yesterday they faced death, today they face Life; and Life murmurs in their souls callings more imperious than the terrifying grunts of returning death.

The preacher’s voice echoes in the sanctuary. The Prussian cannon, unknowingly, respects it and ceases its barrages for a moment:

“God, who asks us to suffer and to die, gives us, with tribulation, and stronger than it, the superhuman joy of having been chosen to be heroes. Go, then, to your death for France with a prayer on your lips and faith in your hearts. To fall for your country is not to die; it is to take eternal life by storm!”

Once the sermon is over, the notes of the Creed resound powerfully through the vaults. And the temple trembles again: the enemy bombs also sing. The Mass continues solemnly… The troops receive Communion and, like incense mixed with gunpowder, raise their thanksgiving prayer to Heaven.

Finally, the soldier-priest traces the sign of the cross in the air and pronounces the blessing. Within the sacred walls, constantly trembling, the clang of bayonets that crown the rifles can now be heard. The army prepares itself in its new headquarters.

…and the Blessed Sacrament in danger

But everything suddenly stops. A storm of iron strikes the vaults, which waver, crumble, and collapse. Everyone runs outside. Only Fr. Duroy, still wearing his chasuble over his uniform, remains in the sacred building. A lieutenant points out the danger looming over his head:

“No!” – exclaims the priest, pointing to the tabernacle – “My duty is to save the Blessed Sacrament.”

Speaking and acting, the priest heads toward the tabernacle. The back of the sanctuary then collapses with a tremendous crash. He does not give in. Boulders fall before him, interposing themselves between the Divine General and his soldier. But he presses on. And his example attracts the others:

“Wait, Father,” shout some soldiers returning to the church, “we will help you save the Good Lord!”

Those arms, so accustomed to digging trenches, push aside the stones and beams. The priest opens the tabernacle and takes the Creator in his hands; the soldiers kneel beneath the tottering dome. Once the transfer is complete, the lieutenant orders their immediate departure.

“Excuse me, my lieutenant,” a soldier carrying some flowers placed inside a piece of shell, as an improvised warrior’s bouquet, requests: “Just two minutes, I’ll take this to the Blessed Virgin. It will be an offering from the regiment.”

What men resurrected by forgiveness can do

It is September 6, 1914. On the front lines beside the Marne, there are two hours left before the battle. In the meantime, the worst of clashes occurs: the wait for a battle that they know will be inevitable, relentless, and merciless. A priest decides to seize the moment:

“My sons,” he says to his brothers-in-arms, “this is going to get heated, and three-quarters of us will not make it back for the afternoon inspection. One bullet or one shell explosion, and then the leap over the wall of existence…”

Private Planteau then speaks on behalf of the others:

“Excuse me, Father. I think this would be the right time for each of us to have a quick word with you, individually of course, because, if you know what I mean…”

Everyone knew exactly what he meant, in fact. Immediately, alone with the priest, each one reveals his moral wounds. The priestly hand rises to heal them.

They are ready! They will demonstrate what a man resurrected by forgiveness can do.

Soldiers attending Mass inside a bombarded chapel in Dommartin (France)

At the foot of the Cross

Two hours pass. The order to attack rings out. Mayhem ensues. Horses and uniforms clash, bayonets are fixed, lead and death rain down. Planteau and his friend Brigeois, who had also been to confession a few minutes before, display feats of bravery. Dargis, the commander, sees them and shouts an order that could only be given to true heroes:

“You two are to climb that hill,” the officer orders, pointing to an unprotected elevation, “and from there you will observe where the enemy artillery is. Then – and here is the hardest part to carry out – you must return and report to me.”

The soldiers try to calculate how many kilograms of molten metal are flying around the hill, but desist. Oh God, what a deluge!…

However, they obey and begin the ascent! When the enemy see two fighters running to the top of the hill, they forget everything else. The reckless duo takes centre stage. Rifles and cannons are fired. And even so, Planteau has the courage for a bit of good humour:

“My friend,” he says breathlessly as he runs, “we’re so insignificant that they point a 77mm battery at us!”

“They certainly take us for General Joffre…”

And so, with a smile, they reach the summit. They prepare to survey the field, but stop reverently. There, high above, a large cross dominates the horizon. They kneel before the Redeemer and pray in the light of the explosions and the sound of the shells that were seeking them:

“My God, You died for us. And, if You so desire, we can repay You in kind. We only ask that, if we fall here, You add us to the honour roll of Your regiment.”

Once the prayer was over, they identified the enemy artillery and intended to descend immediately. At that moment, however, a shell exploded in front of them, and they were both thrown to the ground.

“Are you dead?” Planteau asked.

“I don’t think so. Are you?”

God takes the trench by storm

In the trenches, hours become days, days pass like years, weeks are equivalent to a lifetime and many deaths. And so, months drag by… “The rain of two days ago turned the trench into a quagmire. Yesterday’s battle turned it into a cemetery. Today’s drizzle turns it into a valley of tears. The sky weeps over us: we are already corpses sprinkled with holy water. Yes, another battle is approaching…” These are the gloomy thoughts that assail the trench’s defenders, shrouded as they are in the grey clouds of a sunless day, of a morning that never dawns.

“In these soldiers, the spirit, courage, and hope of victory fade. Translated into the language of war: victory takes ill and dies even before the battle begins…” These are the sombre certainties that contend in the captain’s conscience, daunted by the dark Sunday that is beginning.

Shots whistle continuously over the excavation: the curiosity to raise a head could cost one’s life. But suddenly, a surprise, like an unsuspected bomb, falls on the trench. The clouds remain impregnable against any and all celestial light, the enemy fire never stops shrouding the refuge with its detonations. And yet, the Sun shines in the trench:

“Good day, my sons! I bring you the Good Lord.”

With this, the priest, his cassock billowing in the gust of the bullets and armed with the Blessed Sacrament, storms the French dugout. There is virtually no resistance. The men have already surrendered, kneeling before the Lord of Hosts.

“My friends, I bring you Communion, as some of you have requested. It is the Master who comes to visit you, the invincible Captain!”

Officers, non-commissioned officers, and soldiers feed on the food of the Angels. One or another may give thanks, making Zechariah’s words their own: “through the tender mercy of our God, when the day shall dawn upon us from on high to give light to those who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death, to guide our feet into the way of peace” (cf. Lk 1:78-79).

In the trench, faces pale with doubt and eyes dulled by despair take on the colours of the rising sun. Cheer gains ground as if with a flamethrower. Joy floods the ditch. Enthusiasm overflows in what was once a vale of tears!

“Now,” exclaims a soldier, “they can come!”

“When will we meet them again?” avidly inquires another.

“There they are!” the sentry finally roars, noticing mobilization for attack in the enemy position.

The triple cry echoes from the mouths of officers and machine guns. From the shelter, a counteroffensive begins, furious yet steady, and as such is irrestistible.

All clamber out. The priest is alone with God. He places Blessed Sacrament on a makeshift altar and worships Our Lord to the sound of a concert of roars and gunfire. The war cries compete in their din with the volleys. These begin to fade. The groans and yells then take over centre stage. Thirty minutes pass in this storm. At the feet of the Lord, the sacred minister listens and implores.

Now, however, the voices of victory fill the air. The soldiers return triumphantly to the trenches. They bring with them their wounded comrades. These are the most honoured: their robes are dyed crimson, and the iron medals, embedded by enemy fire, glorify their bodies. They are laid before the Blessed Sacrament.

They die, yes. But before the Divine Sun enclosed in the ciborium, the half-open eyes of these youths rejuvenated by Catholicism contemplate the magnificent dawn of a victory they won and the opening of a Heaven that has won them.

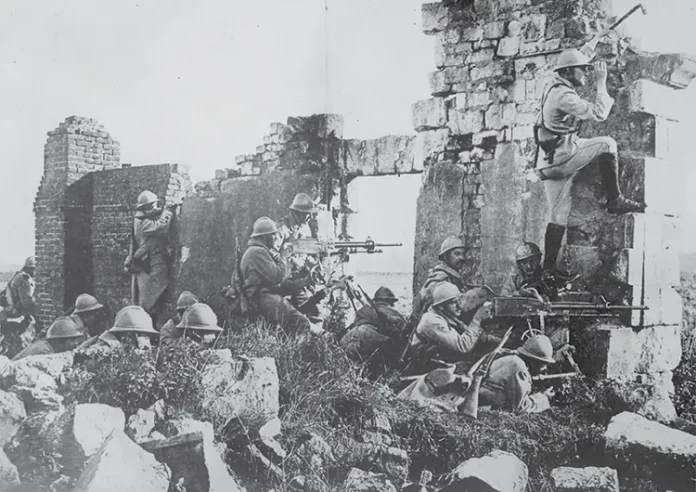

French infantrymen firing from a trench

A few years later

How often, to be a hero, one must be Catholic!

Every soldier recognizes the reality of this principle at the first roar of the cannons: “In war,” explains a combatant who witnessed events like those recounted above, “we are better off without bread than without prayer, and when we attend Mass, we rush into battle with irresistible enthusiasm.”2

But, to be Catholic, one must be a hero!

And now more than ever. For what is heroism if not courage multiplied by courage? What is courage if not advancing despite danger? And what is war if not multiplying danger by danger?

Well, we are at war! Over the centuries, the Church grows in grace and holiness and, therefore, grows in enmity with the devil, the world, and the flesh. War always becomes more complete, and the courage of today’s Catholics cannot be that of past eras. It must be complete, it must redouble. It must become heroism.

The courage to believe in the indestructibility of the Church is not enough. It requires the heroism to remain beneath its vaults, even when they seem to vacillate.

The courage to face life’s thousand dangers is not enough. It requires the heroism to, before the cross that looms on our Calvary, press onward toward the holocaust.

The courage to wait for the sun to rise despite the clouds is not enough for us. We must seek, conquer, and make the invincible dawn of the Reign of Mary rise upon a world that is crawling in the mud, in depression, and in darkness.

“In our days,” Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira prophetically wrote in his school notebook as a boy, “the courage of times of peace is no longer enough. We must choose between being a hero or a coward.” ◊

Notes

1 The historical information contained in this article is taken from contemporary reports, found in: GAËLL, René. Les soutanes sous la mitraille. Scènes de la guerre. Paris: Henri Gautier, 1915.

2 Idem, p.101.