The 21st century. A time in which man’s existence has been made easier on all fronts by the overwhelming progress of science; almost all his needs are met simply and quickly. However, there is one inevitability that technology, however advanced, cannot prevent: failure! It is impossible to find a man who has not failed at some point in his life.

Nevertheless, the word can cause fear, even panic… In a world that has forgotten God, it is hard to understand that mistakes, suffering and trials can be a means for Him to manifest His love for us.

But why did the Creator choose this instrument? What benefit can man derive from disaster? Is it really possible to find grandeur in something so repulsive to our nature as failure?

The original grandeur of the first man

To throw light on this question, let us go back to the beginning of humanity. God created man to reign (cf. Gn 1:26) and enthroned him in Eden (cf. Gn 2:8) to govern all beings, who were subject to his command.

Now we can conjecture that Adam perceived this imperial harmony within himself and contemplated in nature the reflection of the generous magnificence of the Almighty. This interior sensation produced in his spirit a lawful delight in the grandeur that God had placed in him. He felt himself to be the minor monarch of the order of creation and took comfort in being a ray of this divine attribute.

What was the source of Adam’s grandeur? It was the union he possessed with God, for he had been created in His image and likeness (cf. Gn 1:26). Therefore, magnificence was an integral part of Adam’s vocation, since he represented, in a special way, the grandeur of the Most High in the material universe.

Imagining a process of decadence

Contemplating the predilection that the Lord placed in the first man, and seeing how he nevertheless offended Him, it is difficult not to surmise that there had been a previous process that predisposed Adam to sin. To live intimately with God every day and then suddenly fall into a very serious fault does not add up. How did this decadence occur?

Scripture is quite brief in the description of original sin, and offers no indications as to how the fall of the first man began. We are therefore free to raise hypotheses, based on the various processes of spiritual decadence catalogued throughout history. We could speculate, for example, that Adam was going through a dark night of the soul.1

Adopting this hypothesis, we might imagine the father of all humanity wandering through Paradise, praying and asking God to manifest Himself. However, the more he begged, the less he seemed to be heard, because the Creator no longer descended in the paradisiacal dusk to converse (cf. Gn 3:8), no longer spoke to his heart, not even by sensible inspirations of grace. There was nothing to console his soul. Adam was completely desolate and disoriented in the midst of his affliction, without knowing where to turn. God had “forsaken” him!

No longer having the comfort of the Lord’s perceptible company, man began to inhale the “fragrance” of the presence that He had left in nature. Creation was like a photo album that reminded him of God and of the countless graces he had received in his relationship with Him. In this way he sought, in a certain sense, to overcome the tremendous sense of isolation that he was experiencing.

How the devil would have taken advantage of this

The devil – as a consummate psychologist – diagnosed the state in which the first man found himself and, no doubt, tried to take advantage of it.

The creation of Adam – Museum of the Cathedral of Milan (Italy)

He worked on his external and internal senses with the intention of sharpening his sensibility with regard to the wonders of the order of creation. At first, he must have dazzled Adam by emphasizing the natural aspects of the beauties of Paradise, relegating God the Creator to a secondary place, and then, as time went on, inciting him to put Him aside altogether from his thoughts. And that is what probably happened… Our first father no longer admired the divine reflections in the world, but delighted in the splendours of each creature in itself, as if these qualities reflected him, man, and not God.

The ground was fertile for the devil to prompt him take another step towards the forbidden fruit.2

Self-sufficiency leads to mediocrity

Adam began to live a routine independent of God, of “practical atheism”, we might say. He believed in God and even prayed to Him, but he did not keep Him present in his affairs during the day; he did not recall the graces received; he fostered more and more confidence in himself, which gave him the sensation of self-mastery, fortitude and superiority.3

Adam had found a middle position between rejecting God and living the great vocation he had been given. In a word, he had fallen into mediocrity.4

The devil only presented the forbidden fruit to Adam when he saw that he had become accustomed to a state of predisposition to sin, that is, of confidence in himself, lack of vigilance and a naturalistic outlook.

The temptation was “tailor-made” for Adam, and the forbidden fruit was the “consolation” that the devil offered to ease his trial and answer to his aspirations: “You shall be as Gods” (Gn 3:5). In other words, it was the quintessence of a life in which Adam would no longer need God. Sufficient unto himself, he would become the model and master of creation. And we all know how the story ends…

What was Adam’s fault?

In what, then, did Adam’s sin consist?

It would be ridiculous to believe that, simply because he ate a piece of fruit, all humanity saw the gates of Heaven closed to it. It is clear that there is a deeper sin behind it. The material act, represented by the eating of the forbidden food, was a mere consequence of this previous disposition.5

There can be no doubt that if “pride is the beginning of all sin” (Ecclus 10:15[DR]), this was ultimately the cause of our first father’s fault. This, moreover, is a common opinion among the Fathers of the Church.6 However, there is another aspect to be stressed in this chapter of the origin of humanity.

When Adam consented to this execrable offence against his Father, he completed the process of forgetting the Creator which he had already begun: he explicitly refused to be son and slave, in order to be master; he refused to be assumed by the grandeur of God, in order to display his false grandeur; he refused the uncreated Light, in order to manifest his personal brilliance. He desired to equal the Most High, appropriating the gifts received, in order to live off the magnificence he thought was his. Therefore, he formalized his supposed independence from God in order to go his own way.7 Now, we saw at the beginning of this article that Adam’s grandeur came to him from the fact that he was truly a representative of the Creator in the universe. Therefore, by refusing this union with the Lord, his sin directly undermined that grandeur.

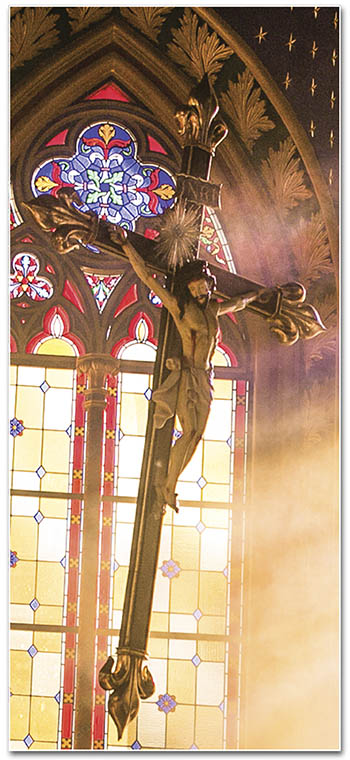

Crucifix in the Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary, Caieiras (Brazi)

The grandeur to which we are all called

Humanity could be divided on this basis: those who recognize their nothingness and allow themselves to be totally taken up by the uncreated Grandeur, who is God; and those who reject it, in order to realize their own grandeur.

All men are called to be great, according to their conditions and according to the vocation of each one. Grandeur is not the exclusive privilege of monarchs or of those called to carry out a prestigious mission in society. To possess it cannot be delimited to wearing rich clothing and participating in pompous ceremonies; it is not the equivalent of conquests made by intrepid generals at the head of invincible armies.

Nevertheless, grandeur acquires its full stature only to the extent that man is united with God. All human glory, apart from this divine relationship, is an ephemeral fireworks display which initially makes an impression, but which the winds of events cause to vanish from the skies of history.

God’s grandeur is perennial and manifests itself above all in moments of misfortune, in failure, in apparent defeat. Often what appears to be a disaster to human eyes is a triumph in the divine sight, “For the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men” (1 Cor 1:25).

The greatest example of this reality is found in Our Lord Jesus Christ, Grandeur incarnate, rejected and crucified, but soon victorious.

We can say that the Creator chose failure as a means to restore and recover the grandeur that man originally possessed, because it is in the crucible of the holocaust that the quality of the human soul is revealed; it is in the throes of suffering faced with magnanimity that true grandeur shines forth.

Grandeur is manifested in our weakness

Moreover, when human weakness appears, favourable conditions are created for the manifestation of supernatural grandeur, as St. Paul states: “It is sown in dishonour, it [the body] is raised in glory. It is sown in weakness, it is raised in power” (1 Cor 15:43).

It is of enormous benefit to us, then, to experience our own weakness, for in this way we prepare ourselves to recognize more easily that the great deeds accomplished do not come from our personal qualities, nor even from the virtues we may practise, but from a sharing in God’s omnipotence, as the Apostle once again declares: “I will all the more gladly boast of my weaknesses, that the power of Christ may rest upon me” (2 Cor 12:9).

Every man carries within himself the tendency – intensified by the effects of original sin – to cling to what he possesses and, unfortunately, even to what he does not possess but only thinks he has. And this distorted concept is often manifested in the spiritual life, even among the most fervent. A method is conceived, effort is applied and, as a result, sanctity is thought to be attainable by one’s own merit, one might almost say “naturally”.

According to this conception, prayer enters into the “production” of progress in virtue as one more element among many others. Now, to remedy this “virus”, God allows monumental failures which oblige us to realize that without Him we can do nothing (cf. Jn 15:5).

For this reason, our life on earth, for each according to his measure, is an alternation of triumphs and failures, so that, once the risks of appropriating divine gifts have been diminished and the conditions created for recognizing our own weakness, we may serve as effective instruments for God’s great interventions. ◊

Glorious Mark of Faithful Souls

The most virginal marriage of Mary and Joseph consisted, above all, in an exchange of hearts by which the graces that inhabited the interior of the one were lived by the other, allowing them to share the same desires.

While the Glorious Patriarch profited from the font of grace found within the Immaculate Heart of the Virgin, She drew from her husband the strength, determination and confidence that pulsated in his fiery heart.

The grandeur of a soul is measured not so much by success achieved in undertakings, but by serene humility in submitting the will to God’s designs and by the determination to advance with confidence despite personal failures, considering them the best path to attaining God’s victory. Serenity in the face of misfortune is the glorious mark of truly faithful souls.

Our Lady and St. Joseph are the most august example of this fidelity – this unpretentiousness and sublime disposition to carry out God’s will, even when it demands acceptance of tragedy and defeat. And only those who are willing to tread this path with generosity, patience and constancy, shouldering all the setbacks and absurdities that the Lord wishes to send them, will follow in the footsteps of the Most Holy Couple.

The failure that God asks us to face today always foreshadows tomorrow’s great victory. Those who, in the cold and darkness of the night of trials and inner struggles, know how to keep the fire of their hearts burning with the warmth of confidence and the light of certainty of victory will be worthy to contemplate, at dawn’s breaking, the splendorous gleam of the Morning Star. ◊

CLÁ DIAS, EP, João Scognamiglio.

Mary Most Holy: The Paradise of God Revealed to Men.

Nobleton: Heralds of the Gospel, 2022, v.II, p.334-335

Notes

1 This is a trial to which specially called souls are subjected, whom God wishes to raise to the highest peaks of sanctity and union with Him (cf. ROYO MARÍN, OP, Antonio. Teología de la perfección cristiana. 4.ed. Madrid: BAC, 1962, p.409). St. John of the Cross gives a detailed description of the terrible spiritual sufferings that accompany it. Here is a small sample: “it [the soul] feels very vividly indeed the shadow of death, the sighs of death, and the sorrows of hell, all of which reflect the feeling of God’s absence, of being chastised and rejected by Him, and of being unworthy of Him” (ST. JOHN OF THE CROSS. Noche oscura. L.II, c.6, n.2. In: Obras Completas. 2.ed. Madrid: BAC, 2009, p.530).

2 Concerning the disposition of soul which preceded Adam’s sin, St. Augustine says the following: “‘For pride is the beginning of sin.’ And what is pride but the craving for undue exaltation? And this is undue exaltation, when the soul abandons Him to whom it ought to cleave as its end, and becomes a kind of end to itself” (ST. AUGUSTINE. The City of God. L.XIV, c.13, n.1. In. Obras Completas. 6.ed. Madrid: BAC, v.XVII, 2007, p.101).

3 “He committed, we would say today, a sin of ‘naturalism’; not wanting to receive from God the norm for his own life, he thought he could suffice himself (self-sufficiency), living his life freely and happily” (BARTMANN, Bernardo. Teologia Dogmática. São Paulo: Paulinas, 1962, v.I, p.450).

4 “Magnanimity is a virtue that leads one to undertake great, splendid and honourable works in all kinds of virtues. It always implies greatness, splendour, eminent virtue; it is incompatible with mediocrity” (ROYO MARÍN, op. cit., p.547).

5 “For the evil act had never been done had not an evil will preceded it” (ST. AUGUSTINE, op. cit., p.101).

6 Cf. BARTMANN, op. cit., p.448.

7 St. Thomas Aquinas explains that Adam’s pride consisted in wanting to resemble God in two ways. One of these coincides with the one we present: “he [the first man] sinned by coveting God’s likeness as regards his own power of operation, namely that by his own natural power he might act so as to obtain happiness” (ST. THOMAS AQUINAS. Summa Theologiæ. II-II, q.163, a.2).