The scenes illustrated on these pages depict one of the most astounding events in history, not only of the Church, but of civilization itself. It is so emblematic that it marked minds and eras since its occurrence in the 11th century.

Much of this symbolic significance is concentrated in the two protagonists of the paintings. On one side is Henry IV, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, the most powerful man of his time, a king of kings. On the other is St. Gregory VII, a simple commoner from northern Italy who had nevertheless been elevated to the See of Peter; he was the Pope.

They were the two supreme potentates of Christendom. And the two most contrasting antagonists.

The Emperor, despite being the sovereign, was a slave to his passions. There was no demand of the flesh that he did not obey, nor any whim of pride to which he did not acquiesce. The Pontiff, on the other hand, was master of himself. A religious from a young age, he was taken from the monastery to guide the ship of Peter; the monastery, however, could never be taken from him, for he continued to dwell there interiorly through contemplation, humility and detachment.

The ambitious Henry IV would stop at nothing – murder, perjury, theft, or any other crime – to increase his power. But St. Gregory VII also had a holy ambition: that the Church “remain free, pure, and Catholic.”1 The clash between the two ambitions thus became inevitable.

Henry appropriated the rights of the Church. He appointed and deposed bishops at will, slandered the Pope and persecuted him with arms. To make matters worse, he had the unfortunate idea of electing an antipope and “excommunicating” the true Pontiff. But the attack backfired. From the height of the Chair of Peter, the Pontiff solemnly excommunicated the Emperor.

The blow was devastating! Henry’s servants and vassals abandoned him, and from one moment to the next, the great potentate, the ruler of the world, the undefeated conqueror, found himself overthrown…

There was only one way for him to regain his lost throne: to beseech the Pope for pardon. And so, Henry went to beg at the door of St. Gregory VII, lodged within the walls of Canossa Castle in northern Italy. It was January 1077, and the coldest winter of the century. Barefoot, wearing penitential sackcloth and with tears in his eyes, for three days the imperial mendicant begged the poor monk for favour.

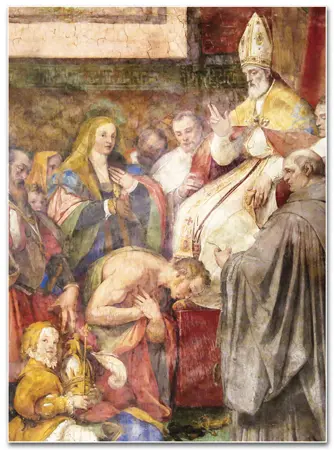

At last, he was received by the Pontiff. On his knees, he declared his unconditional repentance and swore allegiance to the Successor of Peter. He asked for one benefit alone: the lifting of the excommunication that had vanquished him.

Temporal power bowed down to spiritual power. The sceptre recognized the universal dominion of the Shepherd over the entire Catholic flock. Caesar was at God’s feet… in his rightful place.

“Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s” (Mt 22:21). But since “the earth is the Lord’s, and those who dwell therein” (Ps 23:1), what is Caesar’s claim? In fact, what power does he hold except that which comes from Above (cf. Jn 19:11)? What does he possess that he has not received from God (cf. 1 Cor 4:7)?

The mission of secular governments is none other than to guide civil society towards its natural and supernatural end. And this consists in the glory of the Creator and the eternal salvation of souls.2 Legislation that favours sin or prohibits virtue therefore betrays its obligation and is in a state of rebellion against God. Thus, a ruler can only be faithful to his calling to the extent that he kneels before the Lord.

But this is not the only lesson bequeathed to us by the historic event recounted here. By subjugating the Emperor, the Pope made it clear for the centuries to come that it is not the Church that must adapt to the world, but vice versa. As the Vicar of Christ, the Pope receives from Him the omnipotence of truth. And St. Gregory VII knew that it is not by yielding that one conquers for God. ◊

Notes

1 ST. GREGORY VII. Episitola LXIV. Ad omnes fideles: PL 148, 709.

2 In this regard, St. Thomas affirms: “Since heavenly beatitude is the end of a life well lived in the present, it is therefore the duty of the ruling class to seek a good life for the masses, as befits the attainment of heavenly beatitude, that is, by prescribing what leads to heavenly beatitude and prohibiting the opposite, to the extent that it can” (ST. THOMAS AQUINAS. De regno ad regem Cypri. L.I, c.16).