Church institutions arise organically, without prior planning. This is a habitual “method” of the Holy Spirit: to address the problems of the moment, solving difficulties as they arise.

Thus, over the centuries, the complex structure of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, the norms of consecrated life, the various religious orders, and even the regulation of intellectual life emerged.

However, this development did not unfold without impediments. A controversial episode, which attempted to tarnish the indivisible body of the Holy Church, will help us understand how arduous it can sometimes be for a new charism to blossom within this sacred institution.1

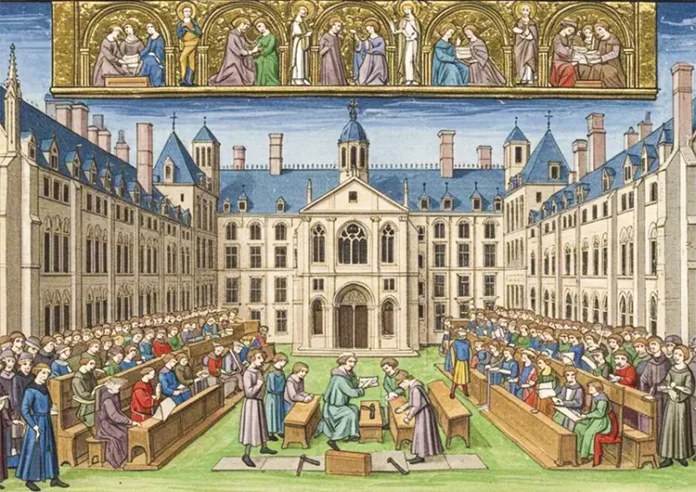

From the Church, universities are born

Throughout the 13th century, various events challenged European Catholics: at times the tense relations between the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire generated conflicts, at others the cause of the Crusades required the settling of disputes in order to unite efforts, and still others, heresies divided Christendom. Navigating these stormy seas, the Holy Church was able to guide, govern, and sanctify its children, keeping pace with the changing times.

Perhaps the intellectual field is the most paradigmatic model of this evolution. After the barbarian invasions, scholarliness took refuge in churches, where palatine, monastic, and episcopal schools originated. But the formation of the cultured man, according to the standards in force in the mid-13th century, made it necessary to adjust the modus faciendi of teaching from the previous period, in which the emergence of cathedral schools made study accessible to all social classes and was the mainstay for the formation of new centres of culture. Thus, universities were born.

Mendicant Orders, a new source of grace for the world

At the end of the 12th century, in the most Christian kingdom of France, the University of Paris took on its definitive profile. It did not take long for it to acquire great prestige before the State and the Church. King Philip Augustus granted it the privilege of immunity and ecclesiastical jurisdiction; Gregory IX legitimized it as an international ecclesiastical institution dependent only on Rome and, through the Bull Parens scientiarum, granted professors the right to go on strike to defend their interests. With its renowned theological authority, the university could be considered the third power of Christendom, alongside the Papacy and the Empire.

However, medieval Europeans saw much more than intellectual life flourish in Europe. The emergence of religious orders that kept alive the enthusiasm for Christian perfection was also a catalyst for promising changes.

While monasticism had predominated in previous centuries, new charisms appeared in this historical period, personified by two providential men: Dominic de Guzmán and Francis of Assisi. With them, the Mendicant Orders appeared on the medieval scene in response to the spiritual needs of the time, soon becoming the standard-bearers of ecclesiastical reform. Thus, the human type of the monk who lived in solitude gave way to that of the friar who, throughout the villages and cities, preached, exhorted, and attracted souls by his example.

The enemy enters the scene…

The fruit of the foundations of St. Dominic and St. Francis was a clergy free from attachments, totally dedicated to the Church. They enlightened Christendom with their writings and teachings, living on alms, working for the cura animarum and constituting a kind of “guard corps” for the Papacy through their complete submission to the Roman Pontiff.

In their apostolic zeal, the Mendicants won the trust of the people, the protection of the civil authorities and the favour of the Popes, which also earned them routine persecution, the result – as is often the case – of the most sordid envy.

In fact, the mendicant friars, despite living in the world, always rowed against the worldly tide, in favour of the salvation of souls; and it was at the University of Paris that the clash between these two mentalities took place with the greatest vehemence.

The admission of Dominicans and Franciscans to the chairs of the Parisian university generated a violent conflict of interest with the professors from the secular clergy, who considered themselves totally surpassed by the newcomers. A two-decade-long struggle ensued, with regrettable episodes of violence, publicity attacks, slander and defamation hitherto unprecedented in the history of the Church.

St. Bonaventure – Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne (Germany)

Perfidy disguised as “concern”

The virulent and tendentious attacks on the Mendicants focused on three aspects. First, the seculars made it clear that the presence of friars at the university was undesirable because of their way of life. Then, since this mere accusation was not satisfactory, they questioned the legitimacy of their ministry. Finally, they contended the state of perfection for pastors and religious, as well as the admission of young vocations.

Such animosity on the part of the seculars seems frankly absurd to us, almost a thousand years after these events. After all, what was the problem with letting them lecture, if the university was supposed to be a centre of culture for all? Perhaps the holiness of life and the quality of teaching of the friars were a constant thorn in the side of the secular professors, who saw themselves as being overlooked in the students’ estimation. But this reality, which we see clearly today, was at the time disguised as “solicitude” for the Church and for the interests of the university…

For the secular professors, the Mendicants were dangerous characters, as they disregarded university statutes and their demands by failing to participate in general strikes. Worse still: under the “disguise” of mendicancy, they monopolized students – who did not have to remunerate them – and influenced them to join their own religious orders, in an act of outright “proselytism”.

An even more unforgivable attitude on the part of the religious was that they obtained three teaching positions during a prolonged strike by the seculars that lasted for years, during which, of course, the mendicant friars, oblivious to the riots of drunken students and indulgent seculars, continued to lecture. During this period, the Franciscans also achieved the conversion of Master Alexander of Hales and his entry into the Seraphic Order.

The catalyst of all discord

The secular masters quickly set about ensuring that their enemies lost the position they had gained. And the main instigator of the persecution against the religious had a name and surname. It was the canon of Beauvais, William of Saint-Amour, who “could not tolerate the advance of these twin Orders, which were gradually taking over university chairs, previously the exclusive preserve of the secular clergy. In writing, from the pulpit and from the chair, he began to attack the Mendicants […]. He attacked their rights and privileges to preach and confess, to bury in their churches; their episcopal and parish exemption, the ideal of poverty in community and even their very existence as religious institutes, ridiculing them mercilessly.”2

Abusing his position as university procurator, William unreasonably diminished the teaching rights of the Mendicants and dragged much of the Parisian secular clergy into the dispute, leading them to believe that their economic income was threatened by the defenceless friars.

The attitude of the seculars, led by William of Saint-Amour, was one of opposition to the novelty and vitality of the Church, in the name of a status quo which they considered to be stable forever. They thus rejected the breath of the Holy Spirit manifested in the Mendicants, on the pretext that their lifestyle differed from the old formulas… For them, the friars were intruders who wanted to work in someone else’s field, as if pastoral care and the doctrinal formation of the faithful were not also their responsibility.

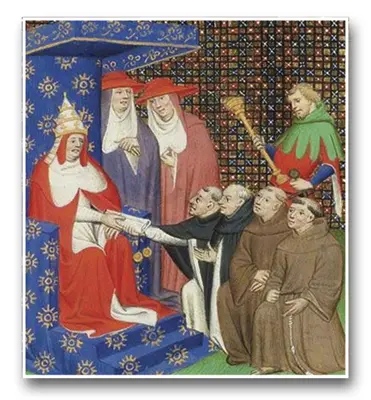

The ultimate goal of the malcontents was nothing less than to suppress the Mendicant Orders or, at least, to hinder their apostolate as much as possible. However, despite constant complaints against the friars and the resulting conflicts, the Church’s ruling was favourable to the religious, as the Papacy was pleased by their loyalty and the orthodox education they offered to young people at the university.

The seculars, obsessed, then decided to resort to creativity: they organized a veritable publicity campaign against the Mendicants, sparing no derision, offensive songs, epigrams and defamatory pamphlets, forcing the poor friars to be often escorted by King Louis IX’s archers during their classes to protect themselves from aggression. They also promoted other strikes, encouraged fights, attributed heretical writings to the religious, and tried to enact new statutory laws in order to exclude them from teaching.

Such slanderers always ended up defeated by the integrity of those they persecuted, until, lamentably, they dared to take their defamation to the Supreme Pontiff…

The friars lose their privileges

Between 1254 and 1266, William of Saint-Amour finally found a good pretext to accuse his opponents. The publication of Introductorius in evangelium æternum, an enthusiastic treatise on the heretical doctrines of Joachim of Fiore3 written by the Franciscan Gerard of Borgo San Donnino, provided the canon with sufficient arguments to write his Liber de antichristo et eius ministris, in which he vigorously condemned the Mendicants as heretics, pseudo-preachers and false prophets.

The complaints of the secular clergy to the Roman Pontiff regarding the discovery of the deviation, allegedly participated in by all the Mendicants – including the Dominicans – had the expected echo in the ears of the Pope, who regrettably refrained from listening to “the other side”. Thus, on November 21, 1254, Innocent IV published the Bull Etsi animarum, which suppressed the prerogatives of the Mendicants in relation to the care of souls, prohibiting them, among other things, from hearing Confessions and preaching, while maintaining a prudent reserve in relation to their functions at the university.

An unexpected turn of events

Two weeks later, on December 7, Innocent IV passed away. While his soul rendered accounts to God, the latter did justice on earth in favour of the friars, through human instruments. Elected as the new pontiff, Cardinal Reinaldo de’Conti di Segni, a well-known protector of the Franciscan Order who took the name Alexander IV, hastened to revoke his predecessor’s precipitated decisions. On December 22, he published the Bull Nec insolitum, which annulled Etsi animarum and granted new privileges to the Mendicant Orders.

It is easy to imagine Saint-Amour’s irritation at the failure of his plans… But he did not desist. In March, he published one of his most famous works, Tractatus brevis de periculis novissimorum temporum, using his usual tactics of defamation and sensationalism. In it, he denounced the “dangers of the latter days” before the Antichrist, which had begun with the founding of the Mendicants, who were, in his opinion, a host of false prophets threatening the Church under the guise of knowledge, piety, and renunciation of the world.

The Dominicans and Franciscans had as their mission to attract the world to the practice of the evangelical truths they lived, and the goal of De periculis was to destroy their raison d’être. Saint-Amour sought to induce society to reject the Mendicant Orders and remove them from teaching and pastoral activities, such as preaching and administering the Sacraments, forcing the friars to renounce alms – a lifestyle that he arbitrarily declared contrary to Divine Law – and to start working the land, like the ancient monastic orders, which meant, in a word, changing their charism and their legal status…

Discerning this perfidious intention with great acuity, Pope Alexander IV condemned the book De periculis on October 5, 1256, with the Constitution Romanus Pontifex de summi. Shortly afterwards, William was removed from his chair.

Bold and controversial defence of the Mendicants

Throughout this dispute, Saint-Amour and his supporters had to face two great enemies they certainly did not foresee.

The debates at the University of Paris confronted the seculars with two of the greatest Doctors of the Church: the Dominican St. Thomas Aquinas and his comrade-in-arms, the Franciscan St. Bonaventure. Far from watching with stoic passivity the war of destruction against their Orders, they used the weapons with which they had been endowed by the Holy Spirit: preaching, letters, prayer, and the art of debate. Why did they do this? The Angelic Doctor answers us: “Holy men resist their detractors for the love of truth.”4

United for the same cause, Dominicans and Franciscans admirably explained various aspects of consecrated life, evangelisation and the care of souls, elucidating them as never before.

St. Bonaventure, who held the position of professor at the University of Paris, published in the summer of 1256 a book entitled De perfectione evangelica, a true doctrinal monument on the evangelical virtues – poverty, chastity and obedience – which constitute the central core of the religious state; later, he also wrote Apologia pauperum, in response to the new attacks against mendicancy initiated by Gerard of Abbeville, an accomplice and continuer of Saint-Amour.

In turn, St. Thomas forcefully refuted Saint-Amour’s accusations in his book Contra impugnantes Dei cultum et religionem, demonstrating on the basis of the Gospels how religious life can combine prayer, study, teaching and itinerant preaching.

He also wrote other works of unmatched clarity in defence of the Mendicants: De perfectione spiritualis vitæ, De ingressu puerorum – which justified the admission of young vocations – and Contra doctrinam retrahentium a religione.

St. Thomas Aquinas, by Fra Angelico – State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg (Russia)

Faced with this resistance, the canon of Beauvais branded the mendicant friars as rebels, disobedient and inveterately proud… It seemed unacceptable to him that the persecuted should bear witness to their own integrity, resist their detractors and defend themselves in court to prevent the closure of their Orders. Against all common sense, he stubbornly repeated the same calumnies, claiming that the friars were only pretending to lead a virtuous life…

There is one final question: who won this clash of titans? The answer is simple. Suffice it to recall that the Holy Church made Thomism the foundation of its own theology, but as for the names of Saint-Amour and his minions, if they survived for posterity, it was not because of the admiration of Christians…

Truth always triumphs

History is a great teacher. Situations similar to those here described were not uncommon in the life of the Church. In fact, God allowed them to happen in order to further His plan of salvation. In effect, heresies led to the clarification of the truths of the Faith, barbarian invasions encouraged the evangelization of peoples, and persecutions solidified the work of the Holy Spirit. They thus became paradigms of how adverse circumstances can cause the holiness of the Mystical Body of Christ to flourish, like a lily among thorns.

Paraphrasing the Apostle St. Paul, we make bold to affirm at the end of these lines: oportet controversiæ esse (cf. 1 Cor 11:19); for it was in the heat of the dispute that the Mendicant Orders brilliantly made clear their own calling and proved to future centuries that new charisms do not arise to destroy the treasure of ecclesiastical tradition, but, on the contrary, preserve it with reverence, adding to the Church the light necessary for its growth in grace.

In this sense, the victory of the Mendicant Orders was not only that of their members, but of the Holy Church and of all Christendom! ◊

Notes

1 This article is a summary, with adaptations of the author’s canonical licentiate in Theology thesis (summa cum laude) from the Pontifical Bolivarian University of Medellín (2025): An inspiring model for the present day: how the Mendicant Orders harmonised the “cura animarum” with the intellectual path.

2 APERRIBAY, OFM, Bernardo. Introducción general a cuestiones disputadas sobre la perfección evangélica en San Buenaventura. In: Obras de San Buenaventura. 2.ed. Madrid: BAC, 1949, v.VI, p.5.

3 Italian abbot and mystical philosopher. His thinking and works gave rise to various millenarian philosophical movements, often condemned by the Church.

4 ST. THOMAS AQUINAS. Contra impugnantes Dei cultum et religionem. Pars IV, c.2, ad 5.