“No one is a good judge in their own cause,” as the saying goes. Or, to use the words of Our Lord Jesus Christ: “If I bear witness to myself, my testimony is not true” (Jn 5:31). The reader may have already applied this principle, even unintentionally, or heard it applied by someone else – possibly a non-Catholic – to the doctrine of papal infallibility.

Indeed, it seems to be a closed circuit for the Pope to affirm: “Since everything I say is inerrant, I declare that I cannot err.” That is, the only guarantee of his infallibility lies in his own word. It would sound like the “quia nominor leo”1 of the old Roman fable.

But the reality proves to be quite different. Firstly, because it was not a Pope who created the dogma of papal infallibility; secondly, because not everything the Pope says is infallible. Let us clarify…

Roman primacy throughout the centuries

To begin, we must consider that from the very beginning of the Church, the Pope has been considered the supreme authority in the Church.

The first testimony that the Roman Church has dominion over all others is found in the writings of a non-Roman author from the 1st century. St. Ignatius of Antioch, in his letter to the faithful of the community of Rome, calls it “[the Church] which also presides in the place of the region of the Romans […], and which presides over charity.”2 It should be noted that some theologians interpret the word charity as a reference to the universal Church; others, however, affirm that it means the totality of supernatural life and, in this way the Roman Church would have the authority to guide and direct everything that refers to the essence of Christianity.3

Also, St. Jerome, while in Syria, writes to Pope St. Damasus to consult him on some questions relating to the Arian heresy and declares: “I meantime keep crying: ‘He who clings to the chair of Peter is accepted by me.’”4 In the same vein, St. Irenaeus explains that it has always been necessary for the whole Church, that is, the totality of the faithful, to be united to the Roman See, “on account of its preeminent authority.”5 And, throughout the centuries, the expression of St. Ambrose became famous: “Ubi Petrus, ibi Ecclesia”.6

Finally, we will spare the readers a long list of references to the Fathers and Doctors who defended the sovereignty of the Pope in the Church, as well as the biblical foundations of such doctrine. This is well summarized by the First Vatican Council, citing the Council of Ephesus, held in 431:

“For no one can be in doubt, indeed it was known in every age that the holy and most blessed Peter, prince and head of the Apostles, the pillar of faith and the foundation of the Catholic Church, received the keys of the Kingdom from Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Saviour and Redeemer of the human race, and that to this day and for ever he lives and presides and exercises judgement in his successors the bishops of the holy Roman see, which he founded and consecrated with his blood.”7

Gold and silver emerge amidst thunder

Having reached the 19th century, despite the numerous revolutions, schisms, and heresies through which the Church passed, one truth could not be removed from the hearts of the faithful: the highest earthly authority of the Mystical Body of Christ is the Pope.

Nevertheless, of what does this authority consist? Some exaggerated, believing it to be absolute in all areas. Others feared that a dogmatic definition in this regard would result in an abuse of the Ecclesiastical Magisterium.

Indeed, throughout the centuries the Holy Father was not always a model of holiness; the sovereign of the Catholic Church sometimes held inappropriate political opinions; the captain of the Barque of Peter made mistakes…

The moment had therefore arrived, after nineteen centuries of implicit faith, to elucidate this doctrine. Blessed Pius IX occupied the Papal Throne. Having already spent twenty-three years in this ministry – his pontificate was one of the longest in history – he clearly perceived that, in such a delicate situation, there would be no better way to proceed than to convene an ecumenical council, that is, a meeting of Bishops from all over the world to discuss a vital matter of the Church.

Pius IX wanted a council worthy of the subject matter; he desired that as many bishops as possible participate in this historic moment. Thus, more than seven hundred ecclesiastical dignitaries entered in solemn procession on that December 8, 1869, under a sky that, like at Mount Sinai, offered its thunderous homage to the new tablets of the Law, which, despite being rock-solid, were now represented by the gold and silver of the Fisherman’s Keys.

Thus began the First Vatican Council, which, having begun with the greetings of celestial storms, was destined to end attacked by earthly ones…

The initial plan of the council, manifested in the outline Supremi Pastoris, aimed to speak of the Church and the primacy of the Pope. It was only later that Pius IX added the topic of infallibility, which was put on the agenda on March 7. After numerous discussions and difficulties, almost all the conciliar fathers voted for papal infallibility – only two prelates voted against – and it was solemnly proclaimed on July 18, once again with a thunderous celestial accompaniment.

On July 19, the Pope suspended the conciliar sessions for a few months; soon after, however, the Franco-Prussian War broke out and the French troops withdrew from Rome, leaving the way clear for the Italian liberals to invade the Papal States. Unable to continue the Council, in October Pius IX suspended the sessions indefinitely, but the most important aspect had already been achieved: the proclamation of the dogma of papal infallibility.

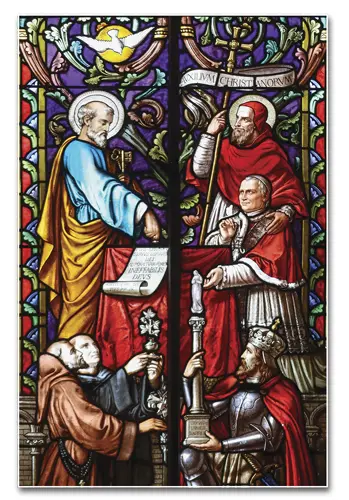

Pius IX declares the dogma of the Immaculate Conception – Church of Saint-Sauveur, Plancoët (France)

This confirms what we stated above: no Pope created this dogma – it was already alive in the Tradition of the Church, based on Scripture, and was made explicit and proclaimed by the decision of an ecumenical council. It suffices to analyse exactly what was defined.

Is the Pope truly infallible in everything?

The answer to the question above is simple: no.

A curious paradox surrounds this doctrine: infallibility is guaranteed for the person of the Roman Pontiff, although one cannot properly speak of personal infallibility.

In other words, the Pope, head and leader of the universal Church – that is, as a public person – possesses infallibility, but the private person of the Bishop of Rome does not enjoy this privilege.8 This is why, for example, if he were to renounce this office, he would immediately lose the exceptional assistance of the Holy Spirit.

Thus, the Pope is infallible only when he uses his authority, in an act in which he manifestly invokes this privilege, that is, symbolically seated in his pontifical chair – hence the Latin expression ex cathedra – and not when he expresses his personal opinions.

Furthermore, the subject matter must concern Divine Revelation, that is, matters of faith or morals. Therefore, a papal pronouncement on political, social, ecological, etc., issues will not be infallible.

Guide, model and hope

Having made these considerations, a doubt may remain: we know that the Pope is not a tyrant who invents doctrines at his whim, and we have seen that he is infallible only under certain conditions – which are so restricted that few truly infallible pronouncements have been made since Pius IX; do we conclude, therefore, that a faithful Catholic can live disconnected from the Roman Pontiff, as long as he follows the infallible doctrine proclaimed throughout the centuries? Not at all!

Although papal infallibility is restricted to matters of faith and morals, and the Roman Primacy refers to the discipline of the universal Church, the Pope is not merely a sort of guideline that must be followed only to avoid going astray.

“You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my Church, and the powers of death shall not prevail against it” (Mt 16:18); “Feed my sheep” (Jn 21:17). These words of the Divine Master to St. Peter show him not only as the holder of authority, as judge and arbitrator. They reveal that the Supreme Pontiff is also – and, we would venture to add, primarily – the Supreme Shepherd, the father of all the faithful, the sweet Christ on earth.

The faithful, therefore, have the right and the duty to look to the Bishop of Rome as guide, model, and hope.

Guide, because through his magisterium – not only the infallible, but also the ordinary magisterium – he is a source of teachings relating to the Faith.

Model, because the Holy Father not only has the obligation to be holy, like all other baptized people, but, as Vicar of Christ, the Saviour Himself grants him superabundant graces so that his life may be a model for the sheep. It is sufficient for him not to resist divine action.

Hope, because in a chaotic and destabilized world like ours, where so many blind guides and so many false models are presented, where truth is distorted or hidden, good is denied and beauty is defiled, where, finally, faith seems excluded from institutions and souls, we remember the words of the Saviour: “Simon, Simon, behold, […] I have prayed for you that your faith may not fail; and when you have turned again, strengthen your brethren” (Lk 22:31-32).

In other words, it is the duty of all Catholics to devote their best sentiments to the happily reigning Pope, and to pray that he may always be the “beacon that illumines the dark nights of this world.”9 ◊

The World’s Greatest Moral Force

Written in the early 1940s, with images typical of that time, Dr. Plinio’s article, partially transcribed below, reveals the perennial power of attraction of the Vicar of Christ on earth.

Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

Peter, the first Pontiff, upon receiving the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven from the Master, first received His Divine Heart. Possessing the Heart of Christ, capable of loving all humanity, Peter could be Christ on earth. […] This is the august mystery that makes the Roman Pontiff the universal Father of peoples, the provident distributor of the bread of truth, the sure guide on the tortuous paths of peace and justice.

For twenty centuries humanity has recognized him as such. Despite the struggles, persecutions, and aberrations of all times, individuals and peoples, great and small, in moments of sorrow and misfortune, turn to Rome, appealing to the one who, without distinction of caste or race, hears all, welcomes all, consoles all, and blesses all. The moral strength of the Pontiff is the same as always, today, yesterday, and throughout all periods of history. He is the point of attraction for all intelligences and all hearts. His majesty, sublime and exalted above all, surpasses the human, and reaches the divine. King of a tiny State, he is seated on a throne that is the guarantee of all thrones, because he is the great infallible moral authority that, more than the trappings of power and the valour of armies, defends order.

Whoever, wishing to know the real moral power of the Pontiff, need do no more than to stand, one day, on the first steps of the staircase that leads to the Vatican. “Who is passing by?” He would ask, at every moment, enmarvelled. It is a rich gentleman, from overseas. He has travelled around the globe; he has visited all the wonders of the world. He has reserved the greatest of all for last: before returning to his British Isles, or to his America capitals, he wants to see the Pope of Rome. “Who is passing by?” It is a Sister of Charity, with her white veil fluttering in the wind. She left an orphanage, a shelter, a school in the most isolated rural area of India: she comes to kiss the feet of the Holy Father, to return, happy, among her orphans and consecrate her whole life to him. “Who is passing by?” It is a venerable prelate, with white hair and aged, worn down by cares. He comes from Canada, from the Rocky Mountains or from the immense grasslands of South America. He comes to see the Holy Father, to implore his blessing. “Who is passing by?” It is the ambassador of the most powerful sovereign in the world. He is Protestant, but he does not hesitate to honour the septuagenarian, who is king only of a tiny state, but who is the universal Father of all peoples. “Who is passing by?” It is a missionary from Japan, a religious from Spain, a missionary from Africa. They come to report to the Vicar of Christ the success of their efforts, the fruit of their apostolic labours. “Who is passing by, with all this pomp, with all this retinue?” It is a Christian prince, an august descendant of the ancient warriors who repelled the barbarians, who waged the crusades. Bearing in his veins the blood and in his heart the sentiments of his ancestors, he does not fail to come and place at the feet of the sweet Christ on earth the tribute of his affection, the homage of his subjects. “Who is passing by?” It is a pilgrim from Poland, a monk from Armenia or Syria, a man of letters, a humble daughter of the people, a freethinker, a naval captain. All anxiously climb those stairs. They impatiently traverse the halls of the Vatican, to see the elderly man dressed in white, to kiss his hands and feet, to hear his voice, to receive his blessing. And then, radiant with joy, they descend, blissfully returning to their lands, to their homes, to their tasks – never to forget that auspicious day.

This is the story of every day, of every week, of every month, of every year. This is the story of every century. Such is the mysterious force, the centre of the new Rome, which, emanating from the Vatican, radiates throughout the world, touches hearts, penetrates everything, moves all. And when an afflicted or devoted soul does not have the good fortune to approach the Holy Father to present a grievance or proclaim his love, behold, even from distant lands, it casts a glance and a cry in the direction of the Dome of St. Peter, towering as a beacon of justice.

Philip Augustus, King of France, intending to repudiate his legitimate wife, Ingeborg, Princess of Denmark, unites himself to Agnes of Merania. The unfortunate queen, finding herself alone in exile, far from her own, repudiated and rejected by her unfaithful husband, gives a cry of anguish, but also of unparalleled sublimity: “Rome! Rome!” Oh, how beautiful is that cry of the oppressed soul, of innocence, of the victim, invoking justice from Rome. […]

This is the moral strength of the Pontiff. The same yesterday as today; the same in the past as in the future, the only one capable of saving the world. ◊

The Pope, Vicar of Christ. The Greatest Moral Force

in the World. In: Legionário. São Paulo.

Year XV. No.496 (March 15, 1942), p.1

Notes

1 From the Latin: “Because I am called the Lion”.

2 ST. IGNATIUS OF ANTIOCH. Lettre aux romains, Salutation: SC 10, 125.

3 Cf. QUASTEN, Johannes. Patrología. 3.ed. Madrid: BAC, 1978, v.I, p.78.

4 ST. JEROME. Epistola XVI. Ad Damasum Papam, n.2: PL 22, 359.

5 ST. IRENAEUS OF LYON. Adversus hæreses. L.III, c.3, n.2: PG 7, 849.

6 From the Latin: “Where Peter is, there is the Church” (ST. AMBROSE OF MILAN. In Psalmo XL, n.30: PL 14, 1082).

7 FIRST VATICAN COUNCIL. Pastor æternus, c.2: DH 3056.

8 Cf. GASSER, Vincentius. Relatio in caput IV emendationes eiusdem. In: MANSI, Johannes Dominicus. Sacrorum Conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio. Graz: Akademische Druck, 1961, v.LII, col.1213.

9 LEO XIV. Homily, 9/5/2025.