Essentially egalitarian and sensual, the Revolution has rebelled throughout the centuries against all forms of truth, beauty and goodness. Its ultimate goal, doomed to inevitable failure, is to dethrone God Himself.

On the other hand, the Holy Catholic Church has as her mission to perpetuate the presence of the Divine Master among men, leading them to the safe harbour of eternal salvation and always promoting the greater glory of the Creator.

For this very reason, “the great target of the Revolution is, therefore, the Church, the Mystical Body of Christ, the infallible teacher of Truth, the guardian of natural law and, thus, the ultimate foundation of the temporal order itself.”1

The Counter-Revolution is the daughter of the Church

However, although the character of militance against every of evil is inseparable from the Barque of Peter, the counter-revolutionary struggle constitutes only a limited episode in her two-thousand-year history. It is as limited, from a chronological point of view, as the very “drama of the apostasy of the Christian West”2 that constitutes the Revolution.

The Counter-Revolution is therefore the daughter of the Church and lives only to serve her, as the body serves the soul. This is a very important service, all the more so as it seeks to remove the main obstacle to the purpose of the Mystical Body of Christ: “If the Revolution exists, if it is what it is, it is within the mission of the Church, it is in the interest of the salvation of souls, it is essential for the greater glory of God that the Revolution be crushed.”3

A counter-revolutionary institution par excellence

In this sense, what is said of the Bride of Christ must be said, a fortiori, of her Vicar, the Supreme Pontiff. The very institution of the Papacy is, by its nature, the most contrary to the revolutionary spirit: nothing is more anti-egalitarian than the mere existence of a man who is infallible in matters of faith and morals, to whom all must submit.

It is therefore not surprising that so often throughout history the forces of evil have attacked with heinous fury the Sweet Christ on earth.

Let us remember, by way of example, the infamous attack at Anagni on September 7, 1303. On that occasion, emissaries of the King of France, Philip the Fair, attempted to imprison and depose the Holy Father, Boniface VIII. Some say4 that one of them even struck the Pontiff in the face! He is said to have responded simply: “Here is my neck, here is my head…”5

Fortunately, the attempt was unsuccessful, thanks to the intervention of the local population, who drove the assailants away. However, the Pope’s already weakened health was severely shaken: he died about a month later, in Rome, on October 11 of that same year.

However, the Vicar of Christ’s attitude was not always one of mere passivity.

Shining examples

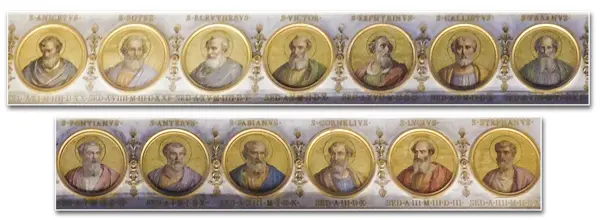

In 1077, St. Gregory VII’s intransigence in defending the rights of the Holy Church, for example, was responsible for one of the most glorious episodes in the history of the Papacy. As the German emperor, Henry IV, proved obstinate on the issue of investitures, going so far as to absurdly proclaim the Pope’s deposition, the latter reacted to this revolt by excommunicating the monarch and releasing all his vassals from their oath of allegiance. Before long, the excommunicated king would be standing at the gates of the fortress of Canossa – barefoot, in penitential garb and under heavy snow – begging for forgiveness from the Holy Pontiff, who was there.

Moving forward to the 16th century, we encounter the eminent figure of St. Pius V. While he fought the Revolution in the ecclesiastical field, zealously applying the reforms of the Council of Trent, he did not neglect external dangers. Faced with the calamitous Mohammedan threat rising from the East, he called on Christian princes to form a Holy League in defence of Christianity. This entirely providential initiative would culminate in the miraculous naval victory of Lepanto in 1571.

The twentieth century, in turn, brings us the memory of St. Pius X’s meticulous and tireless reaction against modernism. Like a zealous shepherd who notices wolves advancing on his flock, he went out to meet the enemy armed with the staff of pontifical authority: his courageous encyclicals, – especially Pascendi Dominici gregis – his public and private admonitions and his example of life blocked the path of this disastrous heresy.

Painful queries

However, the study of Ecclesiastical History also provides us with other recollections, capable of causing perplexity.

Would the Renaissance innovations of the 14th and 15th centuries have succeeded in paganizing Christendom without the indifferent, if not approving, gaze of the Roman Pontiffs? Would the pseudo-Lutheran Reformation of 1517 have succeeded in dragging thousands of souls into a tragic rupture with the Holy Church if it had found in its patron Pope Leo X6 the sagacity of a St. Pius X or the zeal for the faith of a St. Pius V?

And what about the so unjustly celebrated French Revolution? What would have become of it if, instead of the timid and silent semi-condemnation of Pius VI7 it had had to face the apostolic frankness of a St. Gregory VII or the intrepidity of a Blessed Urban II, the Pope of the Crusades?

Surely the Final Judgement will answer these and many other similar questions.

The power of the keys: pledge of victory

In any case – today, as always – we can affirm with Dr. Plinio: “The Papacy possesses extraordinary resources to impose itself. Provided that those who have these resources in their hands use them, the Papacy enjoys possibilities for action, even in our time, which are completely unexplored and entirely unimaginable.”8

What these resources may be, Our Lord declares: “I will give you the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in Heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in Heaven” (Mt 16:19).

With these words, God Himself – remaining ever sovereign and omnipotent – entrusted to St. Peter and his legitimate successors not only the power of influence over temporal society, so well symbolized by the silver key that is part of the pontifical insignia, but above all the golden custody of grace, the “serene, noble and most efficient driving force of the Counter-Revolution”: grace.9

Thus, the dynamism of the Counter-Revolution reveals itself, in papal power, infinitely superior to revolutionary might: “I can do all things in Him who strengthens me” (Phil 4:13).

We therefore have this certainty: the Successor of Peter, even alone, holds in his hands the power to break the destructive work of the Revolution. The day will come when the Pope, like the Prince of the Apostles to Tabitha (cf. Acts 9:40), will command Christendom: “Arise!” And it will rise again. ◊

Notes

1 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Revolução e Contra-Revolução [Revolution and Counter-Revolution]. 9.ed. São Paulo: Arautos do Evangelho, 2024, p.207.

2 Idem, ibidem.

3 Idem, p.209.

4 Cf. LLORCA, Bernardino. Manual de História Eclesiástica. 3.ed. Barcelona: Labor, 1951, p.319.

5 DANIEL-ROPS, Henri. A Igreja das catedrais e das cruzadas. São Paulo: Quadrante, 1993, p.638.

6 Cf. DANIEL-ROPS, Henri. A Igreja da Renascença e da reforma. A reforma protestante. São Paulo: Quadrante, 1996, v.I, p.241.

7 Cf. DANIEL-ROPS, Henri. A Igreja das revoluções. São Paulo: Quadrante, 2003, p.23-24.

8 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Conference. São Paulo, 6/8/1973.

9 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Revolução e Contra-Revolução, op. cit., p.187.