“Grant, O merciful God, that, just as the Saviour of the world, born this day, is the author of divine generation for us, so He may be the giver even of immortality,”1 prays the priest at Christmas Mass.

However, what is the basis of the bold affirmation in this prayer, that today, more than two thousand years after Christ came into the world, He is born for us?

In its prayers, is the Church employing linguistic licence, permeated with beauty but devoid of truth, as faithless scholars sometimes presume? Or perhaps this would be a form of persuasion, urging its believers to revive in their memory facts as ancient as they are important to them, as certain pious persons lacking theological formation conjecture?

The problem arises, and solving it solely based on “faith” seems a truly simplistic and superficial solution. Indeed, sometimes we prefer to say we believe simply so as not to have to explain why we believe, leaving the reason for our faith dubious, until we realize the incoherence this implies.

So, why do we believe that Christ was born for us today? The answer to this question perhaps finds no occasion more propitious for clarification than at Christmas.

It is worth noting, firstly, that Christmas time, in a certain sense even more so than Easter, is laden with elements that impress the senses, fascinating us and creating a palpable atmosphere of innocence quite unmatched throughout the rest of the year.

Scintillating Christmas celebrations

Who does not have nostalgia of watching, as a child, the Christmas tree being set up and laden with charming decorations, which the twinkling lights made appear almost precious to those who admired them? Or, even more so, the preparations for the most important family gathering of the year, a lavish dinner in which the dishes, goblets, and even the apparel seemed to take on new beauty?

As children, who among us did not harbour an inner curiosity to know more about the august Midnight Mass, that celebration we dressed up for, without quite understanding why we were going to attend it?

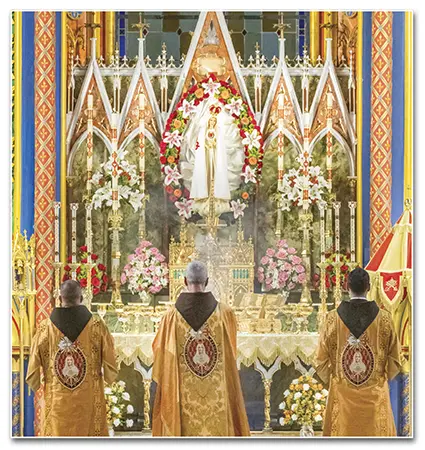

But all of this was merely preparation; entering the church was breath-taking. Even the church seemed more imbued with life: its walls seemed permeated with light; the people were more amiable and communicative; the choir rejoiced in singing accompanied by musical instruments once more; the altar, adorned with abundant flower arrangements, exuded pristineness and decorum; the vestments of the celebrant and garb of the altar servers emphasized the solemnity of the ceremony.

In addition to the delights for the sense of sight, already so gratified, the sense of hearing was also regaled: the bells began to toll. And, beyond this interior bliss – incomprehensible to those who prefer the concupiscence of the flesh – was added the fine scent of rare incense, for its precious aroma reaffirmed the importance of the occasion.

Were it not that the words of the ceremony signify something essentially more important, toward which all these external elements were ordered, our senses would already have been satisfied; however, they would find their true fulfillment only when the palate delighted in the food suited to every taste (cf. Wis 16:20), the Eucharist.

It is Christmas, and the Church proves itself to be the only one capable of bestowing joys that surpass any fleeting pleasure, touching not only our external and internal senses, but the very depths of our souls. To this end, it uses the Liturgy, an effective means desired by Christ Himself to make present to humanity the same graces and blessings bestowed on the most significant occasions of His passage through this world, with a view to Redemption.

In order to evoke this supernatural atmosphere, we call to mind firstly some aspects of Christmas celebrations, by way of example, so that we may better understand the place that the Liturgy holds within the Church and what its study comprises in the ambit of Theology.

An objective and unequivocal path to God

The Liturgy is the set of elements and practices of Christian worship.2 Its existence is explained by man’s need to render to God the praise and adoration that are due to Him, rendering Him a service related to the virtue of religion.3

Through this virtue, man gives due honour to God4 or, in other words, strives to settle his debt to the Creator.5 Cicero6, in his turn, indicted something in this regard when he noted the close relationship between religion and worship.

It is, therefore, through religion that we reconnect with the only and almighty God, according to the view of St. Augustine.7 Now, simply because this virtue commands us to regard the Lord not as an object but as an end, in the manner of an external manifestation,8 it becomes necessary to worship with tangible elements, through which the intimate connection between our body and our soul is addressed.

From the above, we understand how worship must unite both external and internal elements; in truth, human acts proceed from within man, and the full consummation of our offering to God, through the Liturgy, takes place in the combination of our sincerity of heart with external practices.

Christmas Mass at the Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary, Caieiras (Brazil), in 2024

In short, the Liturgy is nothing more than an objective and unequivocal path, traced by Christ Himself and established by the Church, for man to walk towards God.

Mirror of divine action among men

It is in this sense, moreover, that the Liturgy can be understood as a theological place,9 providing reliable and trustworthy information for the understanding of Dogmatic Theology itself, notably through its prayers – lex supplicandi – since they express the meaning of our Faith and what we believe – lex credendi.10

Thus we understand why the Church has progressively, organically and judiciously forged everything concerning its worship, so that the theological reality expressed by the words of the liturgical texts could also be believed through the gestures proper to the rite and the environment in which it takes place.

By way of examples, the conversion processes – more frequently than we imagine – of men of erudition, eminent for their intellectual brilliance, such as Joris Karl Huysmans or André Frossard, who through the blessings of the Liturgy and the irresistible attraction of pulchrum began to return to or enter the Church, seem to suffice.

In this light, we understand Benedict XVI’s bold statement: “Beauty, then, is not mere decoration, but rather an essential element of the liturgical action, since it is an attribute of God Himself and His revelation. These considerations should make us realize the care which is needed, if the liturgical action is to reflect its innate splendour.”11

In other words, the Liturgy is, metaphorically speaking, a mirror of divine action among men. In the field of Theology, it stands as the highest example of God’s manifestation, real and perceptible by the senses, whether through its essential beauty or through the truth expressed in the words of liturgical action, through which the mysteries of that same God being celebrated are actualized.

The means by which the mysteries of Redemption are actualized

Therefore, if we believe that Christ was born for us today, it is because we are convinced that He came into the world in a grotto in Bethlehem more than two thousand years ago, as the starting point of our Redemption, the mystery of which was operated then and is renewed now and, more precisely, actualized by the Church through the Liturgy.

The Child Jesus – Basilica of Our Lady of the Rosary, Caieiras (Brazil)

So between that birth and the one we are now celebrating, there is only one difference: time. The graces can be received in the same way that the shepherds or the Magi received them, as long as our inner dispositions are the same as theirs, in the sense of loving, praising and adoring the Child so fragile, yet creator, born of the Virgin Mary on Christmas night.

Indeed, the Church pleads in the Christmas Vigil Mass: “O God, who gladden us year by year as we wait in hope for our redemption, grant that, just as we joyfully welcome your Only Begotten Son as our Redeemer, we may also merit to face Him confidently when He comes again as our Judge.”12

Thus, through the Liturgy, Christ not only unites Heaven and earth, but He also becomes incarnate sacramentally under the Eucharistic Species, enabling us to encounter Him on the altar, requiring neither a journey as arduous as that of the Magi, nor the announcement by Angels, as was made to the shepherds so that they might go and worship the Newborn lying in the manger (cf. Lk 2:16). He asks of us only the conviction in the power of His Church, the only one capable of bringing the Redeemer to the world every Christmas: “Today a light will shine upon us, for the Lord is born for us.”13

The highest aspirations of humanity are, therefore, embodied in the Liturgy! ◊

Notes

1 THE NATIVITY OF THE LORD. Mass during the Day. Prayer after Communion. In: THE ROMAN MISSAL. English translation according to the Third Typical Edition approved by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and confirmed by the Apostolic See. Chicago: Liturgy Training Publications, 2011, p.175.

2 The list of elements that are part of the Liturgy is vast. Let us mention just a few: liturgical books, the chalice, the ciborium, the tabernacle, the thurible, incense, vessels and linens, the cross, candlesticks, the altar, and the ambo. The practices may be simply related to worship, or related to the specific celebration of a Sacrament or the distribution of a sacramental.

3 Cf. ST. THOMAS AQUINAS. Summa Theologiæ. II-II, q.186, a.1. The term λειτουργία, which conveys the concept of a service directed towards the good of the community, came to refer specifically to the service constituted by the worship of God. Therefore, its meaning has always been rooted in the general benefit and not merely in the benefit of the individual. It is in this context that even the “small” acts performed by the Liturgy are understood to have a public and universal identity in the Church, as they concern the integral worship of God and not merely a private ceremony.

4 Cf. Idem, q.81, a.2.

5 Cf. LABOURDETTE, OP, Marie-Michel. La religion. Paris: Parole et Silence, 2018, p.34.

6 Cf. CICERO, Marcus Tullius. De natura deorum. L.II, n.5-6.

7 Cf. ST. AUGUSTINE. De civitate Dei. L.X, c.3, n.2; De vera religione, c.LV, n.113.

8 Cf. ST. THOMAS AQUINAS, op. cit., q.94, a.1, ad 1.

9 It is worth emphasizing that the Liturgy is essentially the celebration of the mysteries of our Faith, expressed in the life of Our Lord Jesus Christ, whereas Theology is the rational deepening of these same mysteries. However, the Liturgy will be a locus theologicus to the extent that it is grounded in Sacred Scripture and Tradition, reaffirmed by the Magisterium.

10 Here we intend to employ the axiom coined by Prosper of Aquitaine: “Ut legem credendi lex statuat supplicandi – So that the norm of prayer establishes the rule of belief” (De gratia Dei et libero voluntatis arbítrio, c.VIII: PL 51, 209), understood according to the Augustinian perspective of assuming the prayer of the Church, expressed through the Liturgy, as a criterion of Faith.

11 BENEDICT XVI. Sacramentum caritatis, n.35.

12 THE NATIVITY OF THE LORD. Vigil Mass. Collect. In: THE ROMA MISSAL, op. cit., p.171.

13 THE NATIVITY OF THE LORD. Mass at Dawn. Entrance Antiphon. In: THE ROMAN MISSAL, op. cit., p.174.