There is a poem in Brazilian literature by Vicente de Carvalho, Velho Tema I, which discusses the search for happiness in this life. After considering the different forms of bitterness and failure that fill the lives of all men, the poet finally ponders that happiness “we do not attain / because it is only ever where we place it / and we never place it where we are.”

This sagacious consideration prompts us to turn our eyes to the gentle rewards life offers, but which, perhaps caught up perhaps in the whirlwind of mediocre concerns, we do not take advantage of when they visit us.

Among these pure delights that come along our path – and which we so often undervalue – are the springtime impressions received in coming into contact with supernatural truths.

It is not uncommon to find people who, on encountering the Ten Commandments, for example, seem to hear in them the resonance of the divine voice. Over time, the beauty of their formulation is made explicit by reason, followed by adherence or rejection, effected by the will.

Let us then recover one of those innocent lights that perhaps illuminated our childhood, based on considerations made by Dr. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira during a conference for some young disciples.1

Why the Ten Commandments?

What is the purpose of the Ten Commandments? Did God invent them at the moment He wrote the Tablets of the Law and gave them to Moses? Of course not. Before He wrote them on the stones of Sinai, He had already engraved them on Adam’s heart in the form of natural law.2 For this reason, even if millions of years pass and technological-scientific progress reaches unimaginable growth, “the majestically simple words of the Decalogue will defy all time, unchanging.”3

As Genesis recounts, God created Heaven and earth with all that is in them. He gave to each being the characteristics which enable it to move according to its own nature and to enter into perfect cooperation, giving rise to the order of creation. The animals, plants and even the sidereal bodies all move without harming each other, each fulfilling its purpose.

In Paradise, Adam was king by nature; he was to act in correspondence with this charge and according to the condition of the beings he governed, which he knew to their very depths. In so doing, he set in motion the immense perfection of the whole of creation. Yet he sinned, acting not only against the harmony existing in himself and in the beings around him, but above all at variance with the nature of God, who had shown him such favour.

Divine love, however, devised new ways of calling fallen humanity by giving them the Commandments – precepts which man already knew by his nature, but which he had to struggle to fulfil after the devil had sown in him the law of concupiscence.4 Thus, in order to lead him back to goodness, the Creator presented him, in writing, with the laws already engraved in his soul, which also manifested the harmony of the order of the universe and the divine plan for creation.

We see, therefore, that this magnificent set of divine laws does not represent a series of prohibitions coming from a God resentful of original disobedience. In reality, it springs from His infinite love for creatures, and its practice expresses man’s acceptance of this supreme charity.

Love by its very nature transforms the lover into the beloved. If we love vile things, we are transformed into them; but if we love God, we become divine.5

Sin, then, is an act of rebellion against the divine love that comes down to us, a violation of the order it establishes. And therein lies the whole reason for the Ten Commandments: to maintain man’s fidelity to God’s love and to the designs He had in creating humanity.

On Sinai’s height, the Lord gave Moses two tablets. On one were inscribed the first three Commandments, which concern Him; on the other, those which serve to regulate human relationships according to His designs.

Man in face of the divine

Creation itself, with its multifaceted perfections, reveals to us who God is: supreme perfection, supreme wisdom, supreme goodness, supreme justice, supreme in everything! Since God is who He is, and since we are what we are, we must love Him above all things.

This, then, is the First Commandment. Whoever denies any of the Commandments that follow is in essence denying this first one, because all of them are consequences of it.

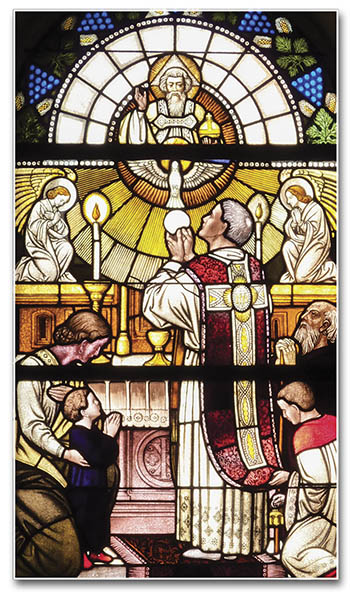

Celebration of the Holy Mass – Church of St. Giles, Oberdrees (Germany)

If we truly love God, we will never pronounce His Holy Name in vain, for, since He is absolutely supreme, to do so without adequate reason is to show disrespect to Him. Therefore, never blaspheme, never mention this Holy Name in frivolous conversations, in jokes, or in jest.

As it touches God, this precept, in a certain way also touches those who have a particular relationship with Him. Accordingly, very sacred earthly and heavenly things should not be spoken of in vain either, because they participate in some way in the divine dignity. Above all, the Most Holy Names of Jesus and Mary deserve every respect.

Dr. Plinio takes the consequences of this Commandment so seriously that he disapproves of the deeply rooted habit in our day of addressing authorities without the proper title, such as, for example, referring to the Supreme Pontiff, a Cardinal, a Bishop or a priest only by their civil name. He extends this prerogative to the family: because of the special veneration children owe their parents, they should never address them simply by their name, but rather as father and mother.

The Third Commandment commands us to observe Sundays and feasts of precept. What does this have to do with God?

On these days He demands a tax from mankind – of not thinking about earning money, not working – which must be paid in the form of… rest! This is a manifestation of the goodness of the Most High, who looks down on each of His children and makes them feel that He is their Father. Moreover, on these occasions there is always a blessing, something festive, pleasant and comforting. It is God’s marvellous way of collecting a tax.

Standard for all earthly power

Honouring father and mother is a consequence of the natural order established by God. Our soul is created directly by the Most High and breathed into the body that our parents generate; the main action is His, but our parents, in a way, collaborate in this creative work. Therefore, if it is true that I must not in any way offend God who is my Cause, then for a lesser but still entirely valid reason, I must not offend my parents who gave birth to me.

Dr. Plinio presents a beautiful metaphor to illustrate this Commandment. Let us imagine that a skilful sculptor moulds a statue in stone, representing a human being in his highest perfection. By some miracle, the statue comes to life and begins to think, speak, move and act independently. At a certain moment, however, it rebels against its sculptor and strikes him. “What? You, the statue that I made, strike me?” The artist’s indignation is justified. Well, the child owes his existence to his parents, and with much more reason. Thus, the precept presents itself: “Honour your father and your mother.”

Moreover, parental power is the standard for all earthly forms of power, which have something paternal about them when they are well understood and well exercised. The honour we should pay to parents is therefore similar to that which leads us to respect authorities.

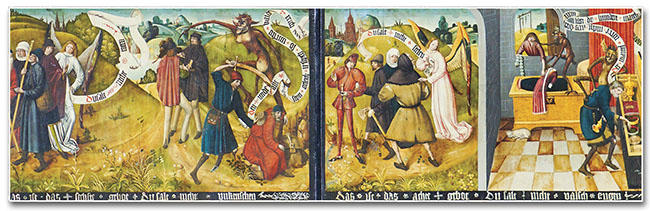

Scenes representing the Third and Fourth Commandments – St. Mary’s Church, Gdánsk (Poland)

It is natural that there should be men who govern others, for even if there were a group of people imbued with excellent qualities and good will, they would not be able to carry out a collective work if they did not have someone to direct them. And since to command is more than to obey, one who commands must be respected.

However, if we demean divine authority by denying it the love that the First Commandment prescribes, how can human authority remain intact? It is impossible.

“I will require a reckoning for his blood…”

“You shall not kill” is the Fifth Commandment. What does this act, which in itself is humanly repugnant, involve? First of all, when someone takes his own life or the life of another, he is violating the natural order for which he was created.

Moreover, when speaking of taking life, there is an implicit reference to the life of the body and that of the soul as well. The latter is injured through scandal, which implies any act that can lead others to sin. “Scandal is an attitude or behaviour which leads another to do evil. The person who gives scandal becomes his neighbour’s tempter. He damages virtue and integrity; he may even draw his brother into spiritual death.” 6 Is there a worse evil than this?

Among the countless examples of murder recounted in the Holy Scriptures is the murder of Abel by Cain. With horror, God himself denounces the wickedness of this fratricide:

“What have you done? The voice of your brother’s blood is crying to Me from the ground. And now you are cursed from the ground, which has opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand” (Gn 4:10-11). In these words we see the divine intention of preserving the covenant with man by providing protection against the murderous violence that comes from original sin. This Commandment forbids the practice of euthanasia, suicide, murder and abortion, preserving human dignity.

The harmonious treasure of chastity

The two Commandments that bear upon the perpetuation of the human species on earth and ensure family stability are the Sixth and Ninth: “You shall not commit adultery” and “You shall not covet your neighbour’s wife.” Far from being instruments of repression for men, they offer them the possibility of becoming like the Angels, by prescribing in a sapiential way the constitution of the family, the relationship between spouses, nuptial chastity and perfect chastity.

Both Commandments are in harmony with man’s original dignity, for they warn him against the tempestuous effects of carnal instincts and pleasures, while at the same time safeguarding the development of the family in a healthy and pure manner. They are in line with the harmony placed by the Creator in His work, and were further justified when Our Lord Jesus Christ instituted the Sacrament of Matrimony.

The reason for “You shall not steal”

A simple syllogism demonstrates the beauty of the Seventh Commandment: man is master of himself and therefore master of his capacity for work; if he is master of his capacity for work, he is also master of the fruit of his labour. Thus, no one has the right to take from him what he has earned through his labour. That is why “You shall not steal”!

As the Catechism of the Catholic Church rightly teaches, the Seventh Commandment “for the sake of the common good, […] requires respect for the universal destination of goods and respect for the right to private property. Christian life strives to order this world’s goods to God and to fraternal charity.”7 Again, this is a consequence of the First Commandment, since the concern is to direct goods to the Creator and to one’s neighbour, so that the purpose for which they exist may be achieved.

A prohibition that encourages the opposite virtue

We have been given a voice to tell the truth. This is the justification for the Eighth Commandment: “You shall not bear false witness.” Lying – that is, saying or doing anything contrary to the truth – leads to error and offends the fundamental relationship of man and of his word with God.8 Truth, however, brings with it the joy and splendour of spiritual beauty, while giving rational expression to our knowledge of reality, both created and uncreated – a fundamental need for man, endowed with intelligence.

Commandments that present a prohibition encourage the practice of the virtue opposite to the vice they condemn. Thus, to forbid lying is to exalt the witness to the truth, the most radical form of which is called martyrdom, when given in defence of the Faith.

Moreover, this precept condemns false testimony, perjury, disrespect for the reputation of one’s neighbour in the form of rash judgement, malice or slander.

“You shall not covet your neighbour’s goods”

Finally, the Tenth Commandment focuses on the intention of the heart and, with the Ninth, sums up the entire Decalogue. That is, not even by thought should we desire a good which belongs to another and which we cannot acquire. The man who practises this precept in its entirety rejoices to see another laden with material or spiritual goods.

This Commandment condemns greed, cupidity, envy.

* * *

This brief meditation on these luminous divine maxims leads us to an act of thanksgiving, because they reveal, above all, God’s extreme care for His creatures and make us exclaim with the Psalmist: “what is man that Thou art mindful of him, and the son of man that Thou dost care for him?” (Ps 8:4).

It also follows that not only the salvation of the soul depends on the practice of the Ten Commandments, but even humanity’s temporal happiness. Either men obey these fundamental divine laws or they will have to resign themselves to never enjoying the tranquillity, peace and joy for which their nature was created. Therefore, the fulfilment of the Decalogue assures us equilibrium in the present life. And therein lies the full scope of the Ten Commandments: even if there were no other laws, with them existence on earth would be almost Heaven.

It is the search for that true happiness engraved in Adam’s soul, lost through original sin and offered again to man through the practice of the Divine Law, which frees him from immoderate attachment to worldly goods, assures him a peaceful relationship with his fellow men, and leads him to the full bliss of the beatific vision of God. Let us find it, then, so that we may never share in the poet’s lament: happiness “is always only where we place it / and we never place it where we are.” ◊

Notes

1 Cf. CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Conference. São Paulo, 17/3/1987.

2 Cf. SÃO TOMÁS DE AQUINO. Decem legis præcepta expositio, proœmium.

3 TÓTH, Tihamér. Os Dez Mandamentos. 3.ed. Porto: Apostolado da Imprensa, 1966, p.10.

4 Cf. ST. THOMAS AQUINAS, op. cit., proœmium.

5 Cf. Idem, ibidem.

6 CCC 2284.

7 CCC 2401.

8 Cf. CCC 2483.