In our days, we are often faced with difficult situations, where a quick decision is required of us, and we lack the help of a neighbour. How should we act on these occasions?

a s we read and hear the narrations of the Holy Gospels, we come across circumstances that manifest the infinite virtues of Our Lord, forming an incomparable ensemble of perfections. In one passage, we see His boundless goodness, ready to forgive everything and attending even the most miserable; in another, His uncompromising justice appears, leading Him to drive out the peddlers and money-changers from the Temple; in a third, it is His profound spirit of recollection which is revealed, in long hours of intimate union with the Father.

Now, there is one virtue without which the panoply of perfections that we see in the God-Man would be unbalanced and incomplete. He showed it particularly in His arguments with the Pharisees and the teachers of the Law, when, faced with malicious traps, He knew how to give the right answer and leave His adversaries in an embarrassing situation. This virtue is sagacity.

An offshoot of the virtue of prudence

To understand sagacity, we first need to know the virtue of which it is an offshoot: prudence.

This cardinal virtue should not be understood in the sense that is generally applied to it in everyday life. A prudent person is not simply one who never takes risks and knows how to avoid danger or inconvenience. True prudence has a broader meaning.

When we have an objective, we may choose various paths to attain it, some more suitable than others. It is precisely prudence that leads us to choose the best route, because it is proper to this virtue to impart “a right estimate about matters of action.”1 to those who practise it.

Obviously, no one is born knowing how to deal with every possible and imaginable situation; this knowledge must be acquired over the course of a lifetime. And this is achieved, according to St. Thomas Aquinas,2 through docility and sagacity.

Those who possess docility know how to turn to others in order to receive teachings that will perfect their judgement. We cannot discover all things by ourselves; hence the need to be instructed.3

Sagacity, in turn, is the quality of soul of those who, faced with new situations, which can often be complex and delicate, discover by themselves what must be done. Aristotle called it “a rapid perception of the middle term.”4

These two virtues complement each other, for the wise man must also be docile, not trusting in his own prudence (cf. Prv 3:5), but in the help of God who will come to his aid, sometimes in the most unexpected occasions, often through the admonition of a parent, friend or teacher. By the same token, a docile person also needs to be wise in order to discern between good counsels and bad…5

Practised in situations that require quick decisions

We will more fully understand the meaning of sagacity and its relationship with prudence if we take the life of St. Paul as an example.

There is not the slightest doubt that this Saint was a shining model of prudence, which unfolded on certain occasions in displays of incomparable sagacity, such as that which took place when he was led as a prisoner before the Sanhedrin, assembled to judge and condemn him.

He immediately realized that Sadducees and Pharisees were there, who did not agree on the resurrection of the dead. To attain his end – to free himself from imprisonment and death – the Apostle raised the controversial subject: “Brethren, I am a Pharisee, a son of Pharisees; with respect to the hope and the resurrection of the dead I am on trial” (Acts 23:6). This statement soon generated such a heated quarrel that they removed St. Paul from their midst, forgetting that they were there to judge him.

So we could say, in a rather informal but perhaps didactic manner, that sagacity is prudence practised at high speed.

Starting from these presuppositions, it seems perfectly legitimate to apply to this virtue a division that St. Thomas6 uses for prudence, provided we keep in mind the following nuance: sagacity is practised in situations that require quick decisions, and without the teaching of others.

Cunning, a false sagacity

Among the various teachings of Our Lord recounted by the Evangelist St. Luke, we find the following: “the sons of this world are more shrewd in dealing with their own generation than the sons of light” (Lk 16:8).

In commenting on these words, St. Thomas raises a curious problem: Our Lord praises the shrewdness of the children of darkness! If sagacity is a virtue, then only the children of light possess it… How can God himself acknowledge it in those who are of this world?7

The solution to this question lies in the fact that sagacity, inasmuch as it is part of the virtue of prudence, has three senses or levels.

The first of these, which is false, is found in those who live in sin, and it consists of rightly deciding what is to be done, but with an evil end in view. This is the case of a thief who is said to be sagacious. His capacity does not come from sagacity, but from the vice of cunning.

Although the word cunning is often applied to good, this is by analogy, just as one can also speak of prudence or sagacity for evil.8 In its proper sense, cunning is always understood disparagingly.

The cunning of the children of this world is found in this first category. That is why Our Lord specifies: “in dealing”. That is, if someone is dishonest, his actions will have dishonest ends.

Shrewdness as regards passing things

At the second level enumerated by the Angelic Doctor, we find a sagacity which, although true, is imperfect. It consists in shrewdness regarding passing things, and not those related to eternal life. This category includes, for example, merchants, military officials and all those who use their prudence to obtain success in their earthly undertakings.

The biblical account of Moses’ early childhood (cf. Ex 1:15-2:9) reveals to us that this is a spiritual characteristic – a very vivid one, in fact – of the chosen people.

By order of Pharaoh, all male infants were to be thrown into the Nile as soon as they were born. Moses’ mother, like many others, wanted to escape this iniquitous obligation. So, instead of delivering her son up to death, she carefully placed him in a basket among the reeds on the riverbank, close to the place where Pharaoh’s daughter often went, and left Mary, the baby’s sister, watching from a distance.

Now it happened that the princess heard the newborn baby crying and, looking around, found the basket. Mary approached and, without revealing her relationship with the child, said she knew a lady who could nurse him. She then led her own mother to Pharaoh’s daughter, who placed the child under her care. Thanks to Mary’s sagacity, her mother now had Moses in her arms again, and even received a salary for it!

Sagacity at its most perfect

It remains for us to consider the last and most perfect degree of this virtue. It is attained by one who deliberates rightly, judges and acts with a view to the ultimate purpose of life. Therefore, one who uses his prudence to attain merit and to make continual progress along the path of sanctity practises sagacity, for man’s aim is none other than “to love, honour and praise God, and by this means to save his soul.”9

Job declares: “The life of man upon earth is a warfare” (7:1). Now, “to win a battle, it is not enough for the warrior to be only strong, but he must also possess the sagacity to either face the enemy head-on or to skilfully evade him.”10 That which applies to physical combat is even more relevant in the conquest of the Kingdom of Heaven, for “there is none more cunning than the devil”11 and it is against him that we are fighting.

Sagacity is necessary both for the individual salvation of each person and for the execution of God’s plans in the unfolding of history, because he who truly loves the Creator will want Him to be praised and glorified by all mankind, throughout the world.

The example of Judith

The example of Judith, narrated by the Holy Scriptures, seems illustrative of this perfect sagacity.

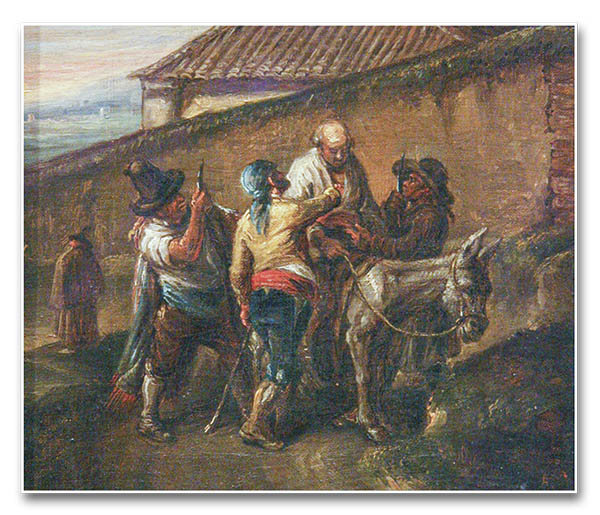

In the days of Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, Holofernes marched at the head of a powerful army with orders to take over all the provinces and devastate those who disregarded the royal decrees. Knowing that the Jews offered resistance, he went to the Israelite city of Bethulia and besieged it. The people, deprived of supplies and without hope of victory, were about to capitulate. In view of this, a widow, inspired by the God of Israel, devised a plan of formidable shrewdness.

During the night, she walked with her servant into the enemy camp. Claiming to be the bearer of a crucial message that would lead the pagans to victory, she easily managed to pass through the ranks of soldiers and enter the Assyrian officer’s tent.

Gifted with an uncommon beauty, it was not difficult to convince those souls given over to impurity. She described the situation in which the Jews found themselves, seeing in that siege a punishment for their sins. They were certain of their defeat and so it would be easy to conquer them. As was to be expected, Judith gained the confidence of the general, who summoned her to stay with him in the camp. She agreed, claiming only that it was her custom to go out at night to pray to the God of her ancestors, which Holofernes benevolently allowed.

Now, on the fourth day, the general summoned the officers to a banquet, at which all, except Judith, gave vent to their intemperance. After supper, she was in the same room as Holofernes, who lay in a deep sleep, drunk with wine (cf. Jdt 12-13).

The fate of the Israelite people lay in the decision of that woman. To whom could she turn? She was alone. Moreover, she had to act promptly; otherwise the Jews would be defeated.

She took the sword that was at his bedside and, after praying to the God of Israel to give her strength, she struck the general’s neck with two blows, cutting off his head. Then she wrapped it in a cloth and left the camp with her servant. As this was already her established custom, the guards took no notice.

When they arrived in Bethulia, great was the joy of the people at seeing their enemy defeated! And even greater was the terror of the Assyrians when, the following day, the Jews attacked them by surprise, displaying the severed head of Holofernes as a banner on top of the wall (cf. Jdt 13-15).

We can all be sagacious

After considering what St. Thomas says about sagacity, and contemplating admirable examples of this virtue, some less experienced souls might imagine that it is something unattainable for those who are taking their first steps in the spiritual life. Perhaps someone might even think: “I already have so many difficulties in dealing with the little problems of daily life… I will never attain this superior sagacity.”

But they are mistaken. All those who possess grace are given an aptitude, at least sufficient, for everything that concerns salvation.12 We should be sure that, whenever God’s cause and our eternal destiny are at stake, as happened with Judith or St. Paul, the Lord will be at our side to inspire us with the right way to act. For, as St. John says: “The anointing which you received from Him abides in you, and you have no need that any one should teach you; as His anointing teaches you about everything” (cf. 1 Jn 2:27). ◊

Notes

1 ST. THOMAS AQUINAS. Summa Theologiæ. II-II, q.49, a.4.

2 Cf. Idem, q.48, a.1.

3 Cf. Idem, q.49, a.3.

4 ARISTOTLE. Analytica posteriora. L.I, c.34.

5 ST. THOMAS AQUINAS, op. cit., q.47, a.14, ad 2.

6 Cf. Idem, q.47, a.13.

7 It should be remembered that the Angelic Doctor cites this passage from the Gospel when dealing with prudence. Therefore, the term cleverness should be understood as synonymous with this virtue.

8 Cf. . ST. AUGUSTINE. Contra Iulianum. L.IV, c.3, n.20. In: Obras Completas. Madrid: BAC, 1984, v.XXXV, p.673.

9 ST. IGNATIUS OF LOYOLA. In: Obras Completas. 2.ed. Madrid: BAC, 1963, p.203.

10 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Conference. São Paulo, Sept. 13, 1969.

11 ST. AUGUSTINE. Sermon XCI, n.4. In: Obras Completas. Madrid. BAC, 1983, v.X, p.597.

12 Cf. ST. THOMAS AQUINAS, op. cit., q.47, a.14, ad 1.