Injustice can penetrate even the most unsuspected areas of human culture. The proof is that it has infiltrated proverbs, as exemplified by the Italian adage: “Traduttore traditore – The translator is a traitor.” But, despite the insult it casts on the honourable profession, this aphorism has its grain of truth.

Who would not consider it a betrayal to translate saudade as añoranza, longing, regret, or rimpianto? The nuances that make our word so expressive become in these translations like a light made to pass through frosted glass: unclear, confused, and indefinite.

An impossible translation

To mitigate this consequence of the sin of Babel (cf. Gn 11:7-9), the translator who does not wish to be a traitor must have perfect knowledge of the language he interprets and the one into which he translates. This applies to grammar, syntax, and semantics, as well as to typical proverbs, the nuances of each expression, interjections, metaphors, ironies, word order and implications… everything, in short, that comprises the eloquence of a people.

But that is not all. It is an obligation to know the work in question thoroughly and, above all, the author: his convictions and intentions, his personality and ways of speaking, being, and understanding, his historical context, his life and experiences. Even before understanding the book, it is necessary to understand who composed it.

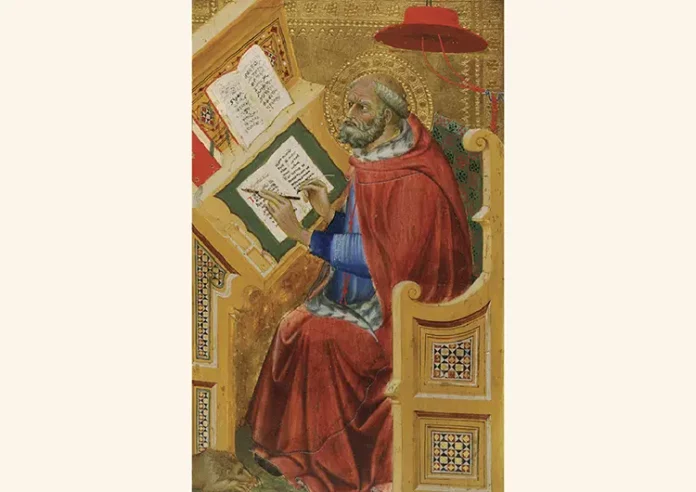

The faithful translation of the Bible was an almost impossible task, but there was one man capable of carrying it out: St. Jerome

I ask the reader to imagine a work that is impossible or almost impossible to translate into another language: a book written in multiple tongues – most of them with distinct alphabets and grammars – and in different literary styles; elaborated over centuries for peoples of every age; endowed with both literal and allegorical meaning; in which there is no superfluous or missing word; whose author, or rather, whose authors were known almost exclusively through this work and who were but “plumes” of a single Author capable of such variety. Would anyone have the courage to undertake such a translation?

Yes, his name was Jerome. And this book is the Holy Bible.

Unintentional preparation

St. Jerome possessed all the qualities mentioned for carrying out such a risky mission: on the human side, mastery of Latin, Greek, Syrian, and Hebrew, as well as literature and exegesis; on the spiritual side, the holiness to orthodoxly understand the sacred pages – an indispensable skill, since only those who love can understand God. How, then, did the Divine Inspirer of the Scriptures prepare His interpreter?

Born in 347 to a wealthy family of Greek origin, in Stridon – the frontier of the Roman Empire and a crossroads of peoples, languages, and cultures – he is sent at a young age to study in the great city. There, he attends four years of classes in grammar, rhetoric, and literature with the renowned Aelius Donatus, reputed to be the best teacher of the time. Jerome distinguishes himself from his peers for his intellectual capacity, his remarkable memory, and his devotion to Roman literature, which resulted in the assembling of an enormous personal library. The first tools for his mission were already in place: Latin, literature, and erudition.

While in this respect he contrasts with his companions, in his customs he is identical: not yet baptized – it was a time when men received the healing waters as adults – with money and licentious friends, without any relatives to restrain him, Jerome leads a life in keeping with the proverbial Roman decadence. However, not for long…

The edict of June 17, 362, promulgated by Julian the Apostate, stripped certain rights from Catholics. But what Caesar did not imagine was that a student would use this onset of persecution to affirm his faith: Jerome, with the ardour of youth and temperament to match, enrols himself among the catechumens and is baptized three years later by Pope Liberius. From then on, he will be a Catholic in the fullest sense of the word – that which today would perhaps be called a “fanatic”… Having completed his studies, he decides to embark on the religious path: he sets out on foot for the East, yearning for the desert. In the spring of 375, he arrives at a coenobitic community in Chalcis, where he spends two years amidst penance, temptations, illnesses, and raptures of love for God. Thus, he achieves another indispensable element of his vocation: holiness.

To escape the seductions of the flesh that continually assail him in his retreat, he spends his time learning Hebrew from a converted Jew. Shortly thereafter, he leaves his ascetic seclusion and, ordained a priest in Antioch, the same place where he had attended exegesis classes, sets off for the Council of Constantinople in 381. There, he rapidly perfects his Greek rudiments and his already ample exegetical foundations. Two steps toward fulfilling the divine plan: fluency in two more of the languages of the Sacred Scriptures – he would forever lack perfect Aramaic – and the art of interpreting them.

A risky mission

The aforementioned Byzantine council closely preceded another held in Rome. Once the sessions opened, we see him drafting the decrees as papal secretary… Yes, Jerome of Stridon, who had recently been a desert monk! Accompanying his bishop to the Eternal City, he was added to the Lateran service because he was seen as a Christian expert – a rarity! – in the biblical languages. Alongside these duties, he wrote and translated extensively, never abandoning his studies.

St. Damasus, Supreme Pontiff at that time, sensing a special calling in the young secretary, tested his abilities: he asked him to explain the meaning of the term Hosanna and resolve other biblical questions. The answers were so swift and brilliant – accompanied by a treatise against the heretic Helvidius and the translation of several exegetical works by Origen – that the Pope dared to reveal from among his concerns a problem that had lingered in his mind for many years: the translation of the New Testament.

In his capacity as papal secretary, Jerome received from St. Damasus the mission of translating the New Testament into Latin

At that time, multiple Latin translations of the sacred pages were circulating throughout the Catholic world: contradictory, flawed, and poor, there were “as many versions as there were manuscripts.”1 This was the so-called Vetus Latina. The solution lay in a revision initiated by a single mind. And this mind could only be that of Jerome. Having reached this conclusion, St. Damasus asked his secretary in 383 for a translation of the New Testament. Delay was something unknown to Jerome, and he finished the work with a rapidity that remains astonishing to this day. In 384, he delivered to the Pope a Latin version of the Gospels, which he had translated based on reliable Greek texts.

Despite the Holy Father’s support, the work received attacks from all quarters. There was talk of disrespect for the ancient editions. But Jerome, supported by the Shepherd of shepherds, feared nothing; to the point that he wrote openly against the dissolute lives of Roman clergy and monks. He feared nothing… until the day of St. Damasus’ death. The persecution that arose against him then forced him to return to the East in 385. From then on, he would reside in Bethlehem.

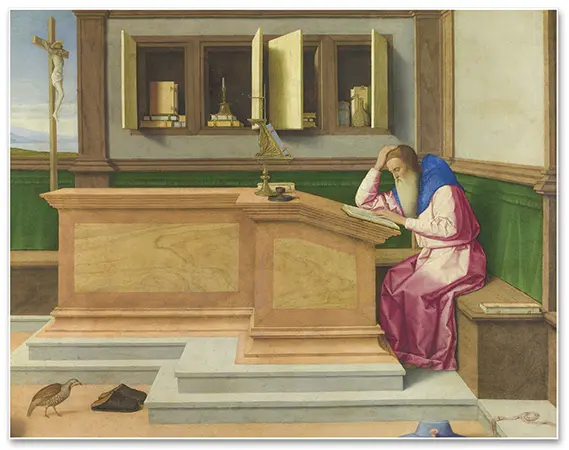

The vocation or the world

In his new home, St. Jerome dedicated himself to continuing the revision of the Latin biblical texts. His goal was now to translate the entire Old Testament into the language of Virgil. The work was more extensive, but appeared less difficult. In fact, the Greek version of the Seventy – the Septuagint – from which the translation would proceed, was an extremely reliable text, the most widely used by the early Church and the most respected, one would say almost sacred. There would be no major obstacles.

Our holy biblical scholar developed his craft by leafing through Origen’s Hexapla,2 which he used to compare the most highly regarded versions of the Old Testament. But as he did so, he became aware of many discrepancies between the Septuagint and the Hebrew. However, he was not bothered enough to abandon the famous Greek version, limiting himself to a few corrections. He was racing toward the completion of the work, and only a grave event could stop him. And it was precisely that grave event that occurred: one morning the translator discovered that the pages containing the fruit of four years of effort – between 386 and 390 – had disappeared.3

The saintly scholar heroically decided to base himself solely on the Hebrew “originals”, and his translation would replace the older Latin texts

Seeing this as a divine sign, he left the Version of the Seventy as a mere prop and resolved to heroically base himself solely on the Hebrew “originals.” Heroism? Yes, for he knew that half the world, or a world and a half, would rise up against him: he had already rejected the traditional Latin texts and now he would “disrespect” the venerable Septuagint Bible… In the eyes of his contemporaries, it was almost sacrilege.

Despite the general jeering, the translator embarked on what he knew to be his calling: in the year 392, he completed the Psalter and the Prophets; by 396, he completed the Historical Books – with the exception of Judges, revised until 400 – and Job; in 400, the Wisdom Books and the Pentateuch. Between 404 and 405, he would complete the Deuterocanonicals, as if carried on wings: he would translate the Book of Tobit in one day and Judith in one night. This set of translations began to supplant the ancient Latin texts and, due to its widespread dissemination, came to be known as the Vulgate.

Thus, despite the lack of human recognition for his work, the Stridonian left the entire Scriptures expertly translated. Later generations would be grateful to him, and rightly so. With the “true Hebrew,” St. Jerome restored to Christians several messianic prophecies that were not understood in the Greek version, eliminated certain confusions, and silenced the mockery of the Jews who laughed at Christian translations.4 Let us add that, unlike many earlier versions, the Vulgate does not translate biblical passages word for word. Furthermore, transposed into Latin with the literary talent worthy of Cicero, its text was a pleasant read for the ever-sensitive ears of the Romans. Let us remember that figures like St. Augustine, and St. Jerome himself, took a long time to acquire a taste for the Sacred Scriptures because of this stylistic detail.5

From Jerome to us

The consequence: the faithful approached the evergreen meadows of Revelation. The Vulgate text was the most copied in history and a favourite among those chosen for the press: its enormous diffusion is a dazzling reality.6 Spread throughout the world, in the Middle Ages it became the great textbook of style and inspiration for writers, scholars, and wise men.

Called the “Vulgate”, St. Jerome’s text spread throughout the world, and was the biblical version upon which the Church solidified her doctrine

More than that, it was the version upon which the Holy Church solidified her doctrine through the councils. One of the decrees of Trent declares that “is to be considered authentic […] the said old Vulgate edition, which has been approved by the Church itself through long usage for so many centuries […] and that no one under any pretext whatsoever dare or presume to reject it.”7 Subsequently, a critical revision was made of it, the New Vulgate, promulgated in 1979 in the Apostolic Constitution Scripturarum thesaurus and used by the Latin Church in the Liturgy and official documents.

Most vernacular versions, moreover, were developed based on the work of St. Jerome. Thus, the Mystical Spouse of Christ hears the voice of her God from this translation, refutes heretics with it in hand, and, by reading it, teaches her children. It is probably the Bible you have at home…

A betrayal?

Finally, the painful question: if the translator is often a traitor, does not the Vulgate betray the Divine Inspirer of the sacred texts? If in Scripture even “the very structure of words envelops a mystery”8 and “from the meaning of one syllable sometimes an understanding about the truth of a dogma is formed,”9 how can we suppose that a translation justifies all the interpretations that two thousand years of exegesis have not yet been able to exhaust? Did not St. Jerome reduce the infinite greatness of God’s Revelation to human fallibility?

On the contrary, the ascetic of Bethlehem conferred security upon human weakness by granting it a reliable version of the Scriptures, and carried throughout the world, without leaving his cell, the seed of the Sacred Word that would blossom in the homilies, meditations, and prayers of so many men and women.

The indisputable authority of the Vulgate derives from a title held by its author. Not that of scholar, exegete, or linguist, nor that of biblical scholar, translator, or man of letters, but what we mentioned before Jerome’s name: Saint. Above all, what earned him the respect of generations was the fact that the Holy Church, always assisted by the Holy Spirit, took him as its own. Humanity rests peacefully upon the sacred pages, knowing that everyone could betray God, except a Saint… and, less still, His own Mystical Spouse. ◊

Notes

1 ST. JEROME. Prólogo a los Libros de Josué y de Jueces. In: Obras Completas. Madrid: BAC, 2002, v.II, p.467.

2 Composed by Origen between 228 and 240, this is the most important work of textual critique in Christian antiquity. It compared the Septuagint text with the Hebrew and other Greek versions of the Old Testament in six parallel columns. Jerome made particular use of the fifth column, which presented the Version of the Seventy. (cf. HEXAPLA. In: HERIBAN, Jozef. Dizionario terminologico-concettuale di scienze bibliche e ausiliare. Roma: LAS, 2005, p.473-474).

3 Cf. BERNET, Anne. Saint Jérôme. Étampes: Clovis, 2002, p.345.

4 Cf. CARBAJOSA, Ignacio. “Hebraica veritas versus Septuaginta auctoritatem”. Existe un texto canónico del Antiguo Testamento? Estella: Verbo Divino, 2021, p.43-53.

5 Cf. ST. AUGUSTINE. Confessions. L.3, c.5, n.9.

6 Cf. BERZOSA, Alfonso Ropero. Versiones latinas. In: Gran diccionario enciclopédico de la Biblia. 7.ed. Barcelona: Clie, 2021, p.2603.

7 DH 1506.

8 ST. JEROME. Epistola LVII, n.5. In: Obras Completas. Madrid: BAC, 2013, v.Xa, p.569.

9 DH 2711.