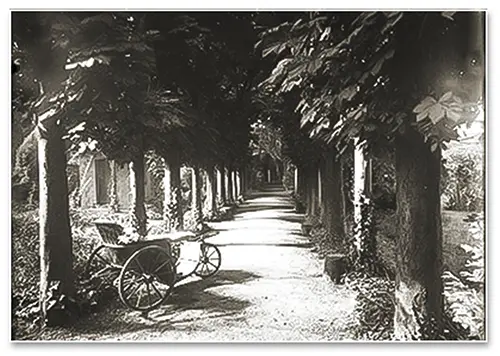

In one of the houses in our movement, there is a very beautiful photograph of a tree-lined promenade. It is by no means as lush as those at Fontainebleau forest, but it is a beautiful arboreal path, dignified, well-arranged and pleasing to the eye. There are a few stone benches without backrests on either side of the walkway, inviting you to sit under the shade dappled by the sun’s rays. It is a long, straight trail, and you cannot see the end of it.

I have the impression that it is a walkway from the convent of Lisieux, where St. Therese of the Child Jesus wrote part of the Story of a Soul.

How enchanting it is to think of St. Therese writing her own story in her tiny handwriting, dressed in her Carmelite habit and sitting in the rays of sunlight shining through that canopy, and at one point to hear her exclaim: “How sweet religious life is!”

The most curious thing is that it is indeed sweet – it alone has sweetness, and sweetness that life in the world does not have – but if we remembered how much Our Lady asked of St. Therese in terms of suffering and how much she gave, then we would understand the battle that religious life entails.

Atoning victim for the merciful love of God

St. Therese received an invitation from grace to be an expiatory victim for God’s merciful love. Mindful that God’s love was so little understood and so little loved by people, she wanted to offer reparation that would first and foremost console the Most High, but that would also have the merit of atoning for those who did not respond with fervour to the vocations they had received and to the movements of God’s love towards them.

In order to ensure that the Lord would not punish this rejection of His love – because such an attitude is an insult to Him – Divine Providence chose a cohort of victim souls who would offer themselves on earth and, in consideration of them, He gave even more gifts to call other souls.

The formula for St. Therese’s sacrifice was: never ask God for anything and never refuse anything; to accept whatever happens. Anything that God allowed to befall her she would consent to it and not become distraught. And with this, she offered one, two, even twenty sacrifices, which she called “small”, because they were not as heroic as those of St. Mary of Egypt – a Saint who made so many heroic sacrifices that in the last century they stopped printing her biography because it horrified souls…

The Saint of the Little Way accepted all the sacrifices allowed by Providence. One day, for example, a nun who was helping her fix part of her habit was clumsy and stuck a pin in her flesh. St. Therese spent the whole day with that pin stuck in her because, God having allowed it, she was not going to take it out. In this way, she offered herself as a victim to God’s merciful love.

Small sacrifices and the great trial

Another day, I can imagine, she was writing her autobiography and, at the moment when her mind was most focused, another nun suddenly came up to her and said:

“Oh, Sister Therese, since you are writing so well, I am going to rob a little bit of your time. Can we talk? I am very upset and I need some consolation…”

“Oh, of course!” – St. Therese would reply.

The conversation lasted an hour… At a certain point, the bell sounded for the meal – a meagre Carmelite lunch – and everyone headed for the refectory. The rest of the day went according to plan, and the Story of a Soul was left for the next day. In everything, she did the opposite of what she would have wanted, because it was her way of offering a sacrifice to God’s merciful love. And if that were all!

One night she expectorated and used her handkerchief. She really wanted to know if she had expelled blood – a precursor to hemoptysis and a harbinger of death – but, in order to offer her sacrifice and mortify herself, she did not turn on the light. The next day, when dawn broke, St. Therese realized that death was near and would finally set her free. It was tuberculosis that was knocking at her door, at a time when there were not the thousand remedies that are available today.

Shortly afterwards, the trial against faith began, the terrible temptation of the saints. She died in tremendous aridity, but this phrase was very characteristic of her state of mind: “I believe, only and exclusively because I want to believe!” She believed because she loved! After a tremendous agony, she had an ecstasy and died. An inexplicable perfume of violets began to emanate from her body and spread throughout the whole convent. It was the glorification of the one who had opened up the Little Way for little souls. What a martyrdom! What an extraordinary thing!

Life is full of great sufferings! How can we face them and be ready for them when they come? They are those colossal waves that come crashing down on everyone. There is no one who does not suffer greatly in religious life and outside of it. Sometimes more inside than outside, sometimes more outside than inside.

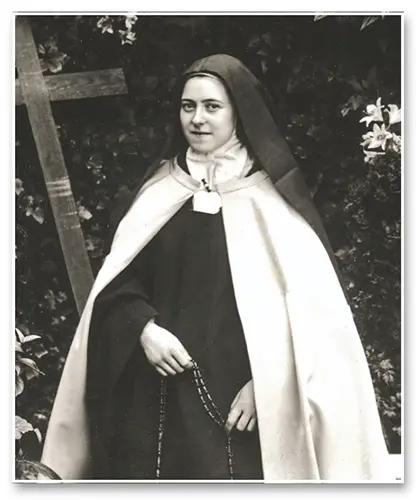

A portrait of the Saint taken in July of 1897

How, then, should we consider the role of suffering?

The proof of fervour is courage in suffering!

The soul who has made the resolution to suffer and is willing to face anything, no matter what, in the worst difficulty and in the dark, determined to reach the final consequences of tribulation if need be, but to embrace duty without hesitation, thinking that life is thus well spent, because that is how it should be and that is how it wants it to be, that is a fervent soul!

If the soul is terrified of tribulation, prefers to joke around, wishes to be funny, entertaining, liked by everyone, to lead a soft life, and is alarmed by any suffering; such a soul can have an ecstasy – which would be a false one – in front of a crucifix or an image of Our Lady to the point of writhing around, but I do not take them seriously, because the proof of fervour is courage in suffering. And any piety that is not accompanied by courage in suffering is a sham.

We have to take a long, hard look at ourselves and understand this: good resolutions made in ordinary life are often not enough. We can, for example, make the resolution: “I wish, O Lady, Queen of Heaven and Earth, to suffer everything possible in the eventuality of great sorrows. And I now give myself entirely!” That is an excellent disposition! But there will come times when the pain is such that we might say: “My Mother, I did not think the suffering would be so great and I do not think I will be able to endure it!”

The true Catholic can bear anything! For a very simple reason: when he asks, he always has God’s grace with him. It is understandable that a man’s natural strength does not offer the resources to cope. But where nature is weak, grace is strong. If one prays, Our Lady will give the necessary strength and, when the time of struggle comes, the temptation will be met head on.

The soul must trust that its capacity to suffer goes much further than the extent of its personality. His situation resembles that of a man who, in order to glorify Our Lady, has to meet a lion along the road and strangle it. He looks at his hands and says: “The lion will devour them and me too! I am not capable of giving him a pinch or even a swipe on his mane, and I am supposed to strangle him! Me? Never!” This person is a failure.

For the fervent soul, the case is put another way: “If this is my duty, and my dedication to the Holy Catholic Church leads me to that point, I will say to Our Lady: Give me graces to endure and I will make it there! ‘Omnia possum in eo qui me confortat,’ says St. Paul, ‘I can do all things in Him who strengthens me’ (Phil 4:13). Our Lord’s strength, obtained through Our Lady’s prayers – which He never denies – will give me strength. At the H-hour, I will be strong!” That is fervour!

To sacrifice many small things is immense in God’s eyes

However, fervour is not only reserved for grand occasions. Anyone who does not have it on lesser occasions is not ready to receive the grace of fervour on grand occasions. And for that, one must be used to making the sacrifices of daily life with this fervour.

When, for example, I have an unpleasant and tedious task to do, and I do not feel like doing it, if it is my duty, I do it and with élan! Then I have fervour.

I can leave an unpleasant task to be done in half an hour, but I will do it now! I must have “gluttony” for sacrifice! And I should not linger idly in the face of a sacrifice that I do not have the courage to make, big or small, it does not matter. Today, at some point, I have to make a bothersome phone call; I have just woken up, so I am going to do it now! I am going to seize this little task with zeal and say: “Come here, telephone, symbol of progress and my servant. My first battle will be through you!”

The sacrifices, I must make them immediately. But if I have a pleasant task to do, I should never give it preference: I should let the impetus pass first and do it later.

In the same way, if I am very keen to hear the repercussions of the apostolate from a member of our movement who has just arrived from a trip – which lasted months – I plan to go downstairs straight away to talk to him. Suddenly I stop and remember to offer Our Lady a sacrifice. I walk slowly down the steps and, with each step, I say an ejaculatory prayer. What for? To torment myself? No! To conquer a little more ground of the cursed, gnostic and egalitarian Revolution. When I arrive downstairs, I will have lost a bit of news, it is true, but I will have gained much ground for Mary Most Holy, who will know what to do with my offering as I slowly descend the staircase. And I know that, on every step, my Angel will accompany me smiling!

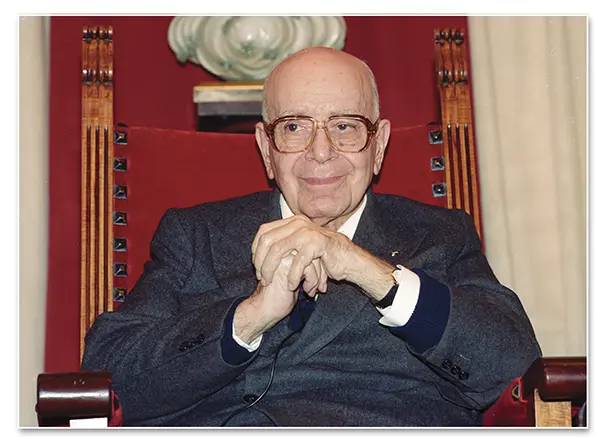

I ask you: is there a sweeter staircase in the world to descend? That is what fervour is all about! Someone will say: “But, Dr. Plinio, that is such a small thing!” I reply: “To do many small things like that is immense! And do them we must!”

we must have it in the small ones, carrying out the sacrifices of daily life

Dr. Plinio in August of 1991

There are therefore a thousand occasions to make sacrifices, both small and large, which increase our fervour. The peak of fervour is reached when, at the height of torment and suffering, at a certain moment a person says: “Everything is done, consummatum est!”

St. Paul, a fervent soul

Look at the beautiful symbolism of St. Paul’s martyrdom. He was the Apostle who worked hardest to spread the Gospel. Before he was beheaded, he declared: “I have fought the good fight, I have finished the course I should have finished. Now, Lord, give me the reward of your glory” (cf. 2 Tm 4:7-8).

When the Roman executioner raised his sword and cut off his head, it struck the ground three times, such was the violence of the blow. At each point where it struck, a fountain sprang up. Such is the sacrifice of a fervent man!

We may feel that something has been decapitated in us during the great sacrifices of our lives, but let us remember the fountains that will spring up through these sacrifices! ◊

Taken, with minor adaptations,

from: Dr. Plinio. São Paulo. Year XXVI. N.306

(Sept., 2023), p.29-32