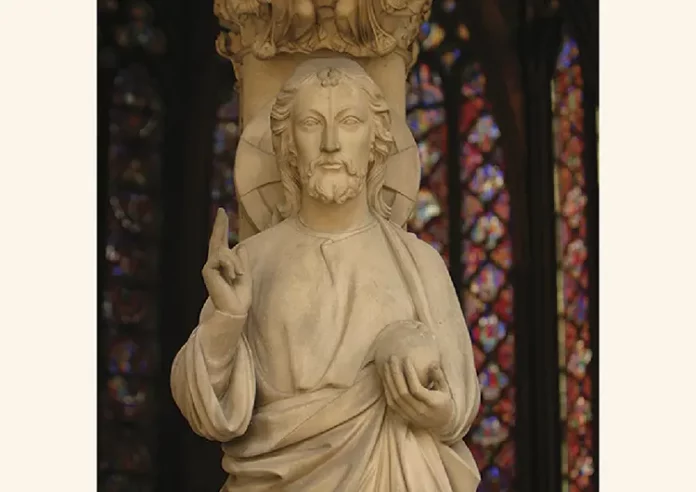

Nothing could be more enchanting than the Gospel scene in which we find Our Lord Jesus Christ surrounded by children so that the Saviour might“lay His hands on them and pray” (Mt 19:13). The disciples, concerned for the Master’s tranquillity, try to send them away… However, Jesus rebukes them and calls the little ones to Him, blesses them by laying His hands on them and even embraces them. On this occasion was manifested that characteristic tenderness which popular piety portrays in the devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, a model of meekness and kindness.

In very different circumstances, the same Evangelists show us Our Lord wielding a rope whip fashioned by His own hands and driving the peddlers out of the Temple (cf. Jn 2:14-16), “with anger, grieved” (Mk 3:5). It is a striking scene: terrified quadrupeds, birds taking flight in confusion, coins scattered on the ground, fleeing vendors stumbling over overturned tables and benches, before the dumbfounded gaze of their customers, who, stunned, also make a hasty retreat…

In a solemn voice, Jesus declares: “My house shall be called a house of prayer; but you make it a den of robbers” (Mt 21:13).

But… can this really be the same Person? How can two such radically opposed ways of being fit into the same soul, the same psychology, the same holiness?

* * *

St. Thomas1 teaches that the human passions, considered in themselves, are merely a capacity for dynamism and are therefore neutral. They become agents of good or evil when man directs them towards a good or evil end, just as the same tool can perform a beneficial service or be used to commit a crime.

However, although the dynamism of passion is a motivational force for man, he must always remain the master of himself and of his actions. If he lets passion take over his conduct, he allows a reversal of roles: becoming the instrument of his own passions, which then dominate him and reduce him from ruler to the one ruled.

In these circumstances, he may become so overpowered by anger that, unable to control himself, he ends up venting his passion on his surroundings, neighbours or family members, who have nothing to do with the cause of his rage. He will be unilaterally dominated by anger at that moment, and there will be no room for compassion. Someone who, on the contrary, allows himself to be dominated by the passion of affection could become so blinded by it that he is unable to discern the evil that those in whom he has naively placed his trust are plotting against him.

One might consequently say that man is under the paradoxical obligation to deny any passion whatsoever – and consequently become an apathetic being – in order to avoid the risk of falling into imbalance. And no small number of people will call this state of apathy “equilibrium”… So what, then, should we prefer? How should we act? With passion or indifference?

* * *

We have the answer when we look at our supreme Archetype. Indeed, we find nothing of this inner conflict in Our Lord Jesus Christ, in whom all is perfection and therefore harmony. He does not have to choose between passion and apathy: His passions are always balanced. How is this explained?

Temperance is precisely the virtue called to “temper” – in other words, to moderate, to control – the dynamism of the passions. Just as a bridle holds back the impetus of a horse that is too fiery, temperance keeps the passions subdued to the will and intelligence, which is led by wisdom. It does not annul them, but keeps them on course, like the rudder on a ship, and never allows them to be anything but an instrument, used rationally. Thus, temperance prevents the passions from inverting the good order of things and dominating the man they are meant to serve.

Accordingly, we do not find Our Lord so attentive to the children that He loses His gravity and seriousness; on the contrary, He dedicates Himself to the apostolate with all seriousness, doing them as much good as possible with a view to their salvation. And in using the whip against the moneychangers, He never lost His composure: His eyes never bulged, nor did His face redden or his hair become dishevelled… Nothing could be further from His supreme and permanent equilibrium. The proof of this is in the verse following the expelling of the moneychangers, in St. Matthew’s version: “The blind and the lame came to Him in the Temple, and He healed them” (21:14).

These are two attitudes, no doubt, but not two ways of being. Jesus, whether scourging a moneychanger or embracing a child, gives us the true example of balance in temperance, the root of which lies in loving God above all things. ◊

Notes

1 Cf. ST. THOMAS AQUINAS. Summa Theologiæ. I-II, q.22, a.3; q.24, a.1-3.