The absence of creativity is one of the most characteristic features of the devil’s work. In fact, if you analyse history with a keen eye, you can see how, over the centuries, the onslaughts of the power of darkness against good have been countless, but always similar in their substance and methods. In this endless repetition, the variation in characters and places is nothing more than a deceptive label for content that is usually the same.

Divine works always marked by a superabundant creativity and renewed vigour, the fruit of the infinitude of their Artifice

Divine works, on the other hand, are marked by a superabundant creativity, the fruit of the infinitude of their Creator. God is par excellence that good father of a family who knows how to bring out new and old things from his treasury (cf. Mt 13:52), and He makes use of the most diverse means in the defence of the Holy Church as well.

Let us focus our attention on one of them, following the story of a young seminarian ardent with zeal for the Catholic cause.

Which path to follow?

Pio Bruno Pancrazio Lanteri was born on May 12, 1759 in Cuneo, a small town in Piedmont close to France and the gigantic Alps. The son of very pious parents, he received an exemplary religious upbringing from an early age. However, when he was only four years old, his mother died, which is why he would later declare: “I have hardly known any other mother than Mary Most Holy, and in all my life I have received no other affection than from so good a Mother.”1

This heavenly Lady had a great mission in store for him, which Bruno must certainly have sensed. Aged just seventeen, he asked his father for permission to enter the Carthusian monastery. Although he loved his son dearly, the good father knew better than to oppose what seemed to be a divine call. Thus, it was not long before Lanteri entered the monastery.

However, he would soon discover that God had not destined him for the cloister. His weak health did not allow him to endure the rigours of Carthusian life, and the prior of the monastery clearly convinced him that if Providence had not given the young aspirant the means to undertake that path, it was because another was reserved for him.

While recognizing that he did not have the vocation to be a contemplative, Bruno still wanted to do something for the Holy Church. So he asked his bishop to accept him as a postulant to the priesthood, and he was soon admitted. In order to continue his studies, he travelled to Turin and entered university – a praiseworthy move, but one that would bring with it great risk.

On the verge of heresy

Close to France, the city of Turin was infected by the same evil that was running rampant in the kingdom of the fleur de lis at the time: Jansenism, which was further aggravated in the Piedmontese domains by a latent atmosphere of opposition between the civil government and the Holy See. The rigorist heresy, full of bitterness, permeated large portions of the ecclesiastical environment, making it difficult for a seminarian to be properly formed.

The danger was all the greater the more widely these deviations were publicized through a poorly governed press, to the great detriment of the people, who generally lacked much theological knowledge. What Bruno needed at that moment was to find someone to guide him, and his infallible Mother would soon send him that someone…

Converted during a reading

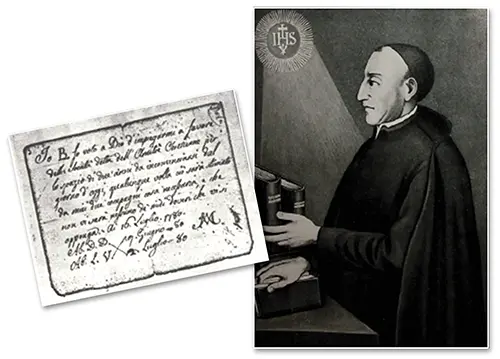

The person in question was a Jesuit – or rather a former Jesuit, since the Society of Jesus was closed at the time – who had a peculiar past.

Nicolas-Joseph-Albert de Diessbach was born on February 15, 1732 in Berne, Switzerland, to a noble but Calvinist family. Possessing a logical and questioning mind, he quickly took an aversion to that fallacious doctrine and declared himself an atheist.

He then decided to pursue a military career and joined the regiment commanded by his paternal uncle, soon reaching the rank of captain. His distinguished origins gave him access to the homes of the best families in the city where he was stationed, and it was during one of these visits that his conversion began.

The host, a fervent Catholic, wisely placed a good book within his guest’s reach. Captain Diessbach was so attracted to reading that he could not help himself. From that moment on, he adhered to the true religion.

A society for doing good

Bruno discerned the path God had mapped out for Him when he met the “Amicizia Cristiana” and its founder, Fr. Diessbach

But Diessbach became too serious a Catholic to be satisfied only with his own salvation. Having joined the Jesuits and begun his apostolic activity, he saw with sadness that Catholicism was being undermined in many ways, not least because of the heresies being broadcast all over the press. Something had to be done.

It was then that he had an idea: to found a society – in this case, a secret one – aimed at remedying the situation. It was 1775 when the Amicizia Cristiana was born. What would this institution actually do?

Good books make good “friends”

The main activity of the Amicizia Cristiana was closely linked to the conversion of its founder. Had his change of heart not come about as a result of good reading? Accordingly, Diessbach strove to make his society a veritable factory of good books.

Its members would scrutinize Catholic writings to check their orthodoxy and fidelity to the Holy See. If the books were found to be commendable, they would not only be archived in the society’s library, but also circulated among the people, who were sadly lacking in true doctrine.

Only six members would make up its board of directors and they would be at the helm of a complex and structured system for collecting data, analysing doctrines, recruiting new members and disseminating approved works.

Exemplary Catholics

Nevertheless, to restrict the Amicizia’s work to this merely practical aspect would be to greatly reduce its true scope. In reality, it was not just a press society, but a sui generis religious congregation.

Much more than great intellectual abilities, what was required of its members was exemplary conduct. An aspirant, for example, underwent a year of continuous scrutiny in order to ascertain the real conformity of his life with Catholic principles. At the end of the assessment period, if he was found worthy, he had to take three vows: not to read any forbidden books for a year; to devote one hour a week to the careful reading of a religious formation book provided by the association; and to obey his superiors in matters related to the good order and the common activity of the Amicizia.2

In addition, certain rules were established for its members, such as regular reception of the Sacraments, half an hour of meditation and reading a day, and a spiritual retreat once a year. In this way, with the help of a well-structured interior life, they would be truly prepared to undertake a fruitful apostolic activity.

Lanteri and the “Amicizia Cristiana”

Needless to say, after meeting Fr. Diessbach, Bruno immediately joined his movement, because he saw in that priest the path that God had mapped out for him. The Jesuit himself realized, in turn – certainly due to a mysterious intuition – that this disciple was not just “one more”. This is shown by the special attention and trust he placed in the young man, who had not yet even been ordained.

He was given to know, for example, the cipher used by the society to keep its correspondence secret, and all or most of it began to pass through his hands.

In 1783, shortly after completing his studies and receiving the priestly anointing, Lanteri became the second man of the Amicizia of Turin, the mother society, of great importance in relation to the others. And with Diessbach’s death in 1798, he definitively took charge of the institution in that city.

Bruno also helped shape and promote the growth of other sister societies, such as the Amiche Cristiane, a women’s organization that exercised an apostolate similar to that of its male counterpart, and the Amicizia Sacerdotale, which aimed to train the clergy. He was also given leadership over the Aa,3 which worked with seminarians.

In the direction of these associations, Lanteri sought to employ all the necessary means for the conservation of the Catholic Faith, progress in virtue and the defence of the Holy See. On this last point, there is a very interesting fact to relate.

In defence of the Pope

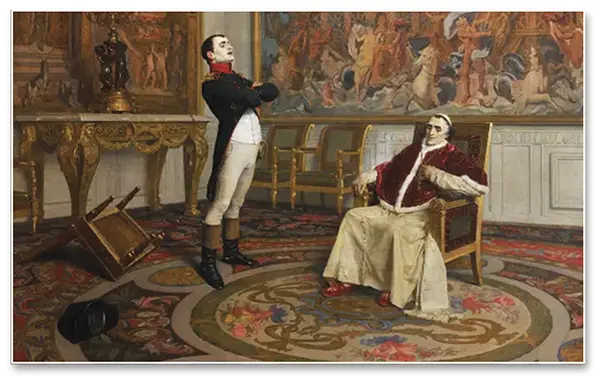

Napoleon was afflicting the whole of Europe. Having made Pope Pius VII his prisoner in Savona, the emperor demanded that he recognize his right to appoint bishops. However, the Vicar of Christ knew that this was an inadmissible practice and, as a result, his position was one of intransigent refusal.

The imprisoned Pope urgently needed help with his plan to defend the Church; where could he find it? Bruno had a solution

However, to be able to strike a decisive blow to the arrogance of the overbearing emperor, and thus safeguard the integrity of the flock, Pius VII needed the official decrees of the Ecumenical Council of Lyon, at which this issue had already been discussed and resolved. With them in hand, he could write a new document – based on the traditional Magisterium of the Church – that would clarify consciences once and for all. But there was an obstacle: the French government had forbidden, on pain of death or exile, the delivery of any writing to the Pope without prior analysis. So how could he have that text brought to him? Bruno had a solution.

He, who had already been carrying out an incessant donations collection to support the august prisoner, decided to prove his fidelity and get the document to him, even if it cost him his life. To do this, he enlisted the help of a gentleman he knew, who was willing to carry the correspondence to the Supreme Pontiff.

Arriving before the Pope, the gentleman knelt to kiss his feet, and at that moment deftly concealed the decrees of the council in the hem of his cassock. Shortly afterwards, the new document of Pius VII was complete. Napoleon was beside himself with rage. “How did this happen?” everyone wondered; the French government did not know what to say…

The cunning of the children of light

Of course, Lanteri’s convenient invisibility would not last forever; his reputation as an ardent Catholic was enough to make him suspect. It was not long before visitors came knocking on his door, with the intention of conducting a search and looking for evidence to incriminate him.

The host, although forced to be hospitable, watched the scene with a curious smile on his lips. In fact, Bruno’s secretary had already anticipated the raid and completely cleared the area of any suspicious papers. One might even wonder if he was not aware of the forthcoming investigation…

In the Church’s defence, the Catholic must use every lawful means in his reach; combining the innocence of the dove with the cunning of the serpent

Indeed, the amicizie’s communication system was extremely efficient. To have an idea of how efficient, it is enough to consider that at the time of Pius VII’s exile, the director general of the imperial police in Rome, Norvins-Montbreton, noted several times that news went from Paris to Rome more quickly through the Catholic information service than through the government’s special couriers!4

It is true that many of the faithful had taken the initiative to help the Pope through secret correspondence, but Lanteri was one of those who knew particularly well how to combine the innocence of the dove with the cunning of the serpent (cf. Mt 10:16).

A lesson

Countless other facts bear witness to this different way of fighting for the Holy Church undertaken by Venerable Pio Bruno Lanteri. Suffice it to say that he founded a religious congregation, the Oblates of the Virgin Mary, and a society similar to the amicizie, but which would be public: the Catholic Amicizia.

In short, the epic of this chosen man holds a lesson: in order to defend the rights and the honour of our Holy Mother Church, Catholics must use every lawful means at their disposal. And, let us remember, there will be no shortage of these, because creativity is not a problem for Divine Wisdom. ◊

Notes

1 GASTALDI, Pietro. Della vita del Servo di Dio Pio Brunone Lanteri fondatore della Congregazione degli Oblati di Maria Vergine. Torino: Marietti, 1870, t.IV, p.21.

2 Cf. PIATTI, OMV, Tommaso. Il Servo di Dio Pio Brunone Lanteri. 4.ed. Torino-Roma: Marietti, 1954, p.42.

3 This society was founded in Paris around 1702 and spread throughout France and surrounding regions, including the city of Turin. Its name is disputed, although it is believed that the mysterious acronym can be deciphered as Amicizia Anonima (cf. PIATTI, op. cit., p.61).

4 Cf. CRISTIANI, Léon. Um prêtre redouté de Napoléon. P. Bruno Lanteri. Nice: Procure des Oblats de la Vierge Marie, 1957, p.88-89.