What most defines the noble is the excellence of their person. By their birth, they are called to guide others and to represent God Himself. Such excellence, however, is imbued with even greater glory when united with the magnanimity of renunciation – so necessary to human existence, especially after being taken to a higher level by the Sacrifice of the Cross.

Renouncing the pomp of the world, she who was born of the noblest royal lineage seems to be an archetypal example of this reality. Madame Louise, the youngest daughter of Louis XV of France and Maria Leszczynska, Princess of Poland, chose a higher path. By becoming the spouse of Christ, she also became, through generosity, a princess of superior splendour.

Education in Fontevraud

Born on July 15, 1737, little Louise was called Madame Septième – the Seventh Lady – although she was the eighth child, as one of her sisters had died. Surrounded by the attentions of twelve courtiers, whose sole function was to accompany her with constant ministrations, she held the power to command and be served from a young age, and had an impetuous and vivacious temperament.

Her education as a girl – along with three of her sisters, Mesdames Victoire, Adélaïde, and Sophie – was entrusted to the Benedictine nuns of Fontevraud Abbey. Thus, she spent her early childhood in the healthy atmosphere of the convent, being masterfully formed in religion and in the love of eternal realities.

Two events especially marked this period. One day, when her maid delayed in attending to her, Louise climbed onto the bed railing and fell… The accident left her with a physical deformity and almost caused her death. The nuns prayed to the Blessed Virgin for her, and miraculously the little girl was cured. The episode marked the beginning of her devotion to the Mother of God.

On another occasion, feeling offended by one of her ladies-in-waiting, she said to her: “Am I not the daughter of your king?” To which the lady replied: “And I, Madame, am I not the daughter of your God?” Thus, baptismal dignity was illustrated to the princess, who immediately apologized, very impressed.

Louise had a very clear conscience, which allowed her to easily correct herself when she noticed her faults, and she demonstrated great zeal for duties of piety, in which she obtained strength for spiritual combat.

She wrote in her Eucharistic meditations: “As soon as my first years passed, as soon as the teachings of Your holy religion penetrated my soul, You brought forth in me an affectionate piety toward the Sacrament of the Altar. I longed for the moment of receiving You in it, of possessing You in it. A living faith and an ardent love, increased by new gifts of Your grace, further increased my desires. You heard them and answered them, God of goodness, You crowned them by giving me Your Sacred Body as food. O gift that I will thank You for until the last moment of my life!”1

On November 21, 1748, Louise made her First Communion, at the age of eleven. In October 1750 she returned to Versailles, where she would remain until 1770. The shock of the difference between the blessed ambience of the abbey and the moral decadence of the French court must have been considerable…

The difference between two worlds

Innumerable excesses in the realm of morality marred the court, where worldly pleasure was the ultimate goal of existence. “No era was more excessively sophisticated, or more urbanely libertine than that one. One could say that everything was permitted, that everything was admitted in the vein of human weaknesses, provided that the rules of etiquette and good manners were respected.”2

Analysing this sad reality with a certain psychological sense, it is not difficult to imagine what it meant for Madame Louise, a righteous and ardent soul, to come into contact with such permissiveness among those who should have been the vanguard of good example and rectitude.

And what was most disconcerting was that this decadence was based on the relativism of the private life of the king, her father, around whom two factions contended: that of the majority of the royal family, which disapproved of his adultery; and the partisans of his concubinage, favouring the licentious behaviour of the sovereign and the interests of the Revolution.

Louis XV – Royal Palace of Caserta (Italy); and Marie Leszczynska, by Charles-André van Loo – Museum of the History of France, Palace of Versailles (France)

Louise maintained open hostility towards the king’s concubines. She allied herself especially with her brother, the Dauphin Louis Ferdinand, whose virtues were well known to the French, both possessing a kindred greatness of soul.

Maria Leszczynska, her mother, was also “the noblest model of all religious and social virtues […]; while she lived, the queen promoted in the court of Louis XV the dignified and imposing aspect that is due to a great power.”3

In this dichotomy of conceptions of life present in the French court, the princess’ adolescence unfolded, and, strengthened by grace, she would choose the most perfect path.

Her vocation becomes clear

It is said that Madame Louise enjoyed arduous and even exhausting exercise. Once, while hunting, her horse became frightened and threw her a considerable distance. She almost fell under the wheels of a carriage that was speeding by.

When offered a ride back to the palace, she refused and asked for her horse to be brought to her. When the nervous animal was presented to her, Louise mounted it, dismissing the concern of those present; she soon dominated it and continued the ride. Upon return to the palace, she thanked Our Lady for this second intervention in her life.

In moments of reflection, events like this certainly sustained her in the practice of good and the exercise of piety.

During this period, God visited the royal family, calling some of its most virtuous members to appear before Him, a fact that marked Louise’s soul. In 1752, Madame Henriette, her sister, died of intestinal tuberculosis. In 1765, the Dauphin Louis Ferdinand died of the same illness, followed by his wife two years later. Her grandfather died in an accidental fire in Poland, and her mother passed away in 1768.

The mourning over these events seems to have kept the princess at court for a long time, since she was concerned about her father. However, she had long since decided to embrace monastic life.

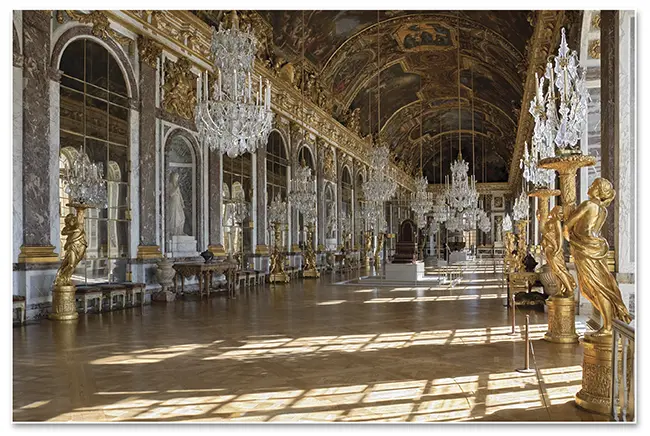

Gallery of mirrors – Palace of Versailles (France)

A Carmelite heart at the court of Versailles

In 1751, Louise witnessed Madame de Rupelmonde’s entry into the Carmelite convent of Compiègne. The ceremony captivated her in every way, helping her to define her vocation.

From then on, the princess became increasingly withdrawn and distant from comforts. She dedicated herself to meditation, following the liturgical year, and for this she sought solitude, despite her lively temperament, which she had to control. “I feel it: He [the Lord] is calling me to something higher, and is drawing me more specifically to His service,”4 she wrote in her notes.

Without neglecting her obligations as a princess – which included official dinners, receptions for ambassadors and military reviews, as well as entertainments such as art exhibitions, balls, games, theatre performances and musical concerts – she began her consecrated life without yet having left the palace. “That everywhere, even in the places most dedicated to the world, I may have a crucified heart, the heart of a Carmelite,”5 she prays in a novena to St. Teresa of Jesus.

In 1762, Louise obtained the Carmelite constitutions and a monastic habit, which she used when she could be alone in her apartments. “My prayers, always prepared by the exercise of the presence of God, to whom I will rise at intervals, will no longer suffer from the vividness of my imagination, from the unhappy dissipation that almost necessarily results from relations with the world, nor from excessive preoccupation with myself.”6

In these words, one perceives Louise’s first conversion and the search for inner recollection, preparatory for the contemplative life in Carmel.

And as she progresses, her conviction becomes firmer: “Everything around me seems to invite me to settle in this land, apparently smiling and happy; everything within me cries out that it is nothing but a place of exile and pilgrimage.”7

Every day the princess makes a thorough examination of conscience. It is thought-provoking to read what she demands of herself in her meditations:

“Have I always seriously striven to examine myself, to follow myself closely, to develop all the habitual motives that guide my actions, to weigh my iniquities on the scales of the sanctuary, to detest them all without reservation or admixture, to prevent them with the necessary measures, to repair them through the holy mortifications of penance, through the humiliations and pains of sincere repentance?”8

It is clear from her own words that Louise leads a humble life, aspiring to sacrifice and to the Cross of Our Lord. She avoids drawing near to the palace’s heating on cold days, overcomes her aversion to the smell of candles, and her difficulty to remain kneeling for long periods. Her dedication to the needy is also well-known: she gives all the money she receives for her personal expenses to the poor, never using it for herself.

Finally, in Carmel

Only the Archbishop of Paris, Christophe de Beaumont, knew of her aspirations to the religious life. The princess made a novena to St. Teresa, asking for strength to overcome her father’s tenderness, and begged the prelate to intercede for her with the king. Louis XV was dismayed by the news and asked for fifteen days to think it over. Perceiving it to be a genuine calling from God, he gave his paternal blessing to his daughter’s vocation.

It was with immense generosity that Louise surrendered herself to God. She knew well that her prayers and sacrifices would weigh on the divine scale in favour of the conversion of her father and the court. “Have I not known enough of the world to hate it forever, to never regret? I have considered so many times, one by one, all the delights of this state, which I wish to renounce,”9 she affirmed.

In expressing her opinion about the princess’ departure, Madame Campan, governess of the king’s daughters, stated: “Madame’s soul was superior, the princess loved great things! She often interrupted my reading, exclaiming: “How beautiful! How noble!” Thus, nothing more could be expected of her than this admirable action: to exchange the palace for a cell and her beautiful dresses for a habit of coarse wool. That is what she did.”10

It is clear that after Madame Louise received the habit on September 10, 1770, at the Carmelite convent of Saint-Denis, with the name Sister Therese of St. Augustine, she was given the most varied opportunities to fight for souls and for France.

Appointed mistress of novices, she gives us an interesting account of this role: “How do you expect me to have a moment to myself when I am in charge of thirteen novices whose fervour must be continually moderated? I only find difficulty when I have to make them take their rest.”11

Shortly afterwards she was elected superior and was admired by the entire community. Sober and serene, with no complacency toward evil or excessive rigour, she distinguished herself by the good sense of her character and by her care of her sisters. She was a prioress who knew how to form heroines of love and selflessness.

The princess also served as treasurer of the community and undertook the reconstruction of the convent church. Several debts acquired previously were resolved by her perspicacity in administration.

For the Church and for France

The Carmelite princess spared no effort interceding with her father in favour of the Church. Later, during the reign of Louis XVI, she sought to influence the sovereign’s indecisive spirit to take the right position and be upright in the exercise of his royal mission. Her influence over him was so beneficial that the Revolution feared her and sought to block this ray of light that shone upon the monarch.

She firmly corrected him for his weakness in signing the Edict of Tolerance, recognizing civil rights for Protestants. She saw in this attitude the influx of ideas from the Enlightenment and the great catastrophes that could hence befall France.

Sister Therese of St. Augustine was also openly opposed to the Jansenist errors that were spreading at the time, seeking to save countless religious who had adhered to this heresy. Moreover, due to the prestige she enjoyed, she obtained from the king the authorization for fifty-eight Carmelite nuns to be received in French territory, after the expulsion from the Austrian states of all contemplative religious, by order of Emperor Joseph II.

Louis XV visits his daughter in Carmel, by Maxime Le Boucher – Museum of Art and History of Saint-Denis (France)

An accurate way to understand her august personality is to look at her correspondence, in which the Carmelite nun and the princess unite to the advantage of the Church and for the public good.

Death by poisoning?

The possibility is raised in History that the princess was poisoned. Indeed, it is said that during this period she received an anonymous envelope containing relics. After opening it, she found a handful of hair covered in a mysterious powder. Upon inhaling it, she immediately felt its noxious effects: “She said not a word, and the doorkeeper saw her quickly throw the envelope into the fire. Madame Louise died a month later, on December 23, 1787, after weeks of atrocious suffering.”12 There was no diagnosis for her illness, and the princess died exclaiming: “At a gallop, at a gallop to Paradise!”

Since everything she did stemmed from a healthy impetuosity, she would not have been any less hasty in the supreme moment of launching herself into the unexpected to conquer Heaven!

Did she fulfil her mission? It is impossible to doubt! Dr. Plinio affirms this, considering the religious revival in France even under the grip of the Revolution: “It is evident: the immolation of the Venerable Louise of France was not unrelated to this, for if the life of the righteous is precious before God, the life of this righteous woman necessarily was of great value to Him, as it was to men!”13

We can affirm without hesitation that Madame Louise’s greatest honour is that of having been an obstacle to revolutionary action in France. Moreover, she contributed to the birth of a religious movement there that opposed these errors and, despite appearances to the contrary, she triumphed before God. ◊

Notes

1 VENERABLE THERESE OF ST. AUGUSTINE. Méditations eucharistiques. Lyon: Théodore Pitrat, 1810, p.47.

2 HENRI ROBERT. Os grandes processos da História. Porto Alegre: Globo, 1961, v.VI, p.158.

3 CAMPAN, Jeanne Louise Henriette. A camareira de Maria Antonieta. Memórias. Lisboa: Aletheia, 2008, p.11.

4 VENERABLE THERESE OF ST. AUGUSTINE, op. cit., p.111.

5 Idem, p.292.

6 Idem, p.106.

7 Idem, p.3-4.

8 Idem, p.103.

9 Idem, p.286.

10 CAMPAN, op. cit., p.13-14.

11 PROYART, Liévin-Bonaventure. Vie de Madame Louise de France. 2.ed. Paris: Librairie d’Education de Perisse Frères, 1849, t.I, p.226.

12 COHALAN, Kevin. Une énigme du Carmel. La princesse empoisonnée. In: Dossier Histoire des Crimes du Plateau. Montreal. Year VIII. No. 1 (March-May, 2013), p.10.

13 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. A força do bom exemplo [The Power of Good Example]. In: Dr. Plinio. São Paulo. Year XXVI. No. 303 (June, 2023), p.24.