Far across the ocean, the Old Continent beckoned all the lovers of sound tradition and refined customs. And these were not in short supply in the “São Paulinho” of the Belle Époque. While Dona Lucilia, as we have seen, figured in their first ranks, esteem for Europe was neither the primary nor sole motive for her trip there in June of 1912.

Resignation in face of the distress of illness

Gravely ill with gallstones, she was in need of definitive treatment for her malady.

From time to time she would be overtaken by a distressing feeling of queasiness which would be followed by sharp pains that obliged her to take to her bed. These attacks became more and more frequent, and she was consequently put on a strict diet. Gallbladder pains can be excruciating, and the treatments used nowadays were unknown back then. In spite of everything, no one in the family ever saw her show the least sign of inconformity, for her temperament had been shaped by resignation.

The attacks of Dona Lucilia’s illness having reached their acme, it was greatly feared that a crisis might result in death. In fact, at the time, cases of death brought on by the condition were not uncommon. While the medical profession knew that the removal of the gallbladder was the only solution in such extreme cases, it had yet to find a way of accomplishing this without placing the patient’s life at grave risk.

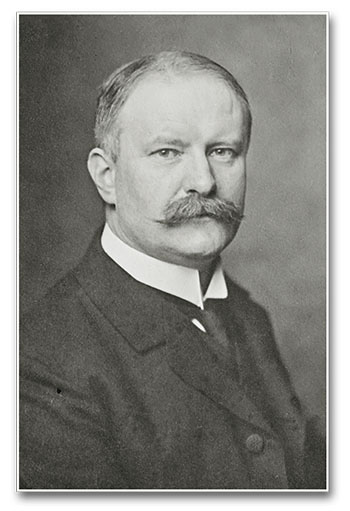

So, when reports spread around the world that Dr. August Karl Bier, the Kaiser’s personal physician, had successfully removed a gall-bladder in Germany, Dona Lucilia’s relatives would spare no effort in taking her to see the famed specialist, impelled by the great esteem they had for her.

Among those accompanying her on the trip were her husband, Dr. João Paulo, her children, brothers, brothers-in-law, nephews, and in a place of honour, her mother, Dona Gabriela. The family travelled by train to Santos and then by ship to Rio de Janeiro, to embark for Europe aboard a comfortable transatlantic ocean liner, on June 11, 1912.

“Don’t worry, my child…”

During the ocean crossing, her nephew Tito, a child with congenital deafness and a difficult temperament, was only too willing to follow the advice he received from many quarters: “Go see Aunt Lucilia; she’s the only one who can calm you down.”

During the trip, he was one of Dona Lucilia’s most faithful visitors. She always welcomed him tenderly and patiently, trying her best to resolve his childish problems.

Because of his impairments, he was neither able to control the volume of his voice, nor weigh the effect that his words could have on a person in Dona Lucilia’s painful situation. He was still young, and lacked a sense of time and place, which explains why he once told her at the top of his voice:

“Aunt Lucilia, they say you’re going to die! But I don’t want you to die!”

The typical reaction to such a tragic prognostication can be easily imagined: tears, discouragement, and the like. But this was not Dona Lucilia’s response.

She pitied the suffering boy rather than herself and replied with a serene countenance and a voiced filled with sweetness:

“Don’t worry, my child. I will not die…”

In the Kaiser’s university hospital

Having crossed the torrid and tropical seas, the steamer entered European waters. Making no stops, it sailed along the Portuguese, Spanish, and French Atlantic coasts, cut through a choppy English Channel, and pushed on through the thick fog of the North Sea. Finally it moored at the famous port of Hamburg, a city steeped in medieval tradition. Because of Dona Lucilia’s condition, the family immediately took a train for Berlin, the capital of the German Empire at an approximate distance of two hundred and ninety kilometres.

Dona Lucilia had to forgo the pleasure of taking in the city sights, even though, for her, observing settings and ambiences was one of life’s most appealing pursuits. Her relatives went on to the magnificent Fürstenhof – Hotel of the Princes – near the Potsdam station. Meanwhile, she was taken straight to the hospital.

Dona Lucilia was to be operated on early in July at the Frederick William Royal University Polyclinic, the apple of the Kaiser’s eye. Every day after breakfast, Dona Gabriela and Dr. João Paulo left the children with the governess and went to be with Dona Lucilia at the hospital. The other relatives also dropped by to see her as much as they could. A description of one of the visits by her mother, husband, and children has come down to us.

Lying in bed, Dona Lucilia seemed more a statue than a living person. Her long black hair hung loose like a curtain behind the pillow. Absorbed in thought, she gazed at the ceiling with her arms extended alongside her body

Despite her condition, her attitude was one of firmness, stability, continuity and determination in face of the risk that had to be taken. Hers was the serene yet unshakable resolve of one who says: “It must be so, and so it will be; God will provide.”

As soon as she noticed her relatives, Dona Lucilia endeavoured to show them her customary tenderness, but it was tinted with gravity and sadness.

A successful operation

The whole family was in suspense over the surgery, including Dona Lucilia herself. While he was an eminent surgeon, Dr. Bier had performed only one gallbladder removal; it was the kind of operation that few surgeons were willing to venture.

Added to this fact were the reports of deaths, or perhaps worse, patients who had been left almost completely incapacitated by serious post-operative lesions. In those days, surgical methods were rudimentary and even anaesthesia was a significant risk.

How would Dona Lucilia’s operation go? Would it be a success? On the day of the surgery, after a morning of uncertainty, her relatives gave vent to their relief when they received word that Dr. Bier had been successful.

While Dona Lucilia’s life had happily been saved, her sufferings would let up only gradually. Her convalescence was painful and complicated due to shortcomings in the medical resources of the time. The pain and suffering she experienced in the days following the operation marked her forever. In less than a week, her hair showed streaks of white.

Dona Lucilia found a way of coping with the pain through her attitude of resignation. She remained reclined and avoided physical effort of any kind in order to conserve her little strength. Her face bore the marks of trauma; she looked as if she had been through an internal “earthquake.”

Nevertheless, whenever her dear children came by, she welcomed them with touching tenderness. Her smile and her affection were never absent during the moments in which they could be close to their mother. Amid her sufferings, she saw the little ones as windows to a brighter tomorrow. ◊

Taken, with slight adaptations, from:

Dona Lucilia. Città del Vaticano-Nobleton: LEV;

Heralds of the Gospel, 2013, p.125-126, 129-131