The few allusions that Scripture makes to this mysterious figure, combined with the commentaries and inferences of the exegetes, reveal to us a personality full of humility, unpretentiousness and faith.

The time when the figure of Apollos emerges in the Acts of the Apostles probably coincides with the end of the year 52, or the beginning of 53, a phase of great expansion for the Church. Although not long after the death of our Lord Jesus Christ – less than twenty years – Christian communities could already be found scattered throughout the Mediterranean region and even beyond!

St. Peter, the first Pope, had moved to Rome about a decade prior. In that same period, St. Paul began the last of his three apostolic journeys. He left the city of Antioch – the “headquarters” from which he used to begin his journeys – and travelled “from place to place through the region of Galatia and Phrygia, strengthening all the disciples” (Acts 18:23).

St. Luke, in the Acts of the Apostles, tells us of the epic feats of these two men, pillars of the Church. However, in the eighteenth chapter of his work, he interrupts the narration, to fix his gaze on another place…

First mention of Apollos

The author of the Acts turns to the port city of Ephesus, located a short distance from where the Apostle was, and also home to a Christian community. St. Paul had been there not long before, and had left two great friends and disciples of his there, the couple Priscilla and Aquila.

It is in Ephesus that a personage appears who attracts attention: “Now a Jew named Apollos, a native of Alexandria, came to Ephesus. He was an eloquent man, well versed in the Scriptures. He had been instructed in the way of the Lord; and being fervent in spirit, he spoke and taught accurately the things concerning Jesus, though he knew only the baptism of John” (Acts 18:24-25).

In Alexandria, a coastal city of Egypt close to Israel, St. Mark had founded a community, still in its infancy. Apollos was rightly supposed to be just a catechumen, having received only John’s baptism, a public invitation to penance and preparation for true Christian Baptism.1

Apollos was a fearless man. He began to preach boldly in the synagogue, and the orthodoxy of his doctrine – although incomplete – coupled with the courage with which he spoke, made him an attraction in the city. Priscilla and Aquila, hearing of this unusual figure, decided to attend one of his discourses and were favourably impressed: “when Priscilla and Aquila heard him, they took him and expounded to him the way of God more accurately” (Acts 18:26).

Here the sacred text reveals a beautiful aspect of Apollo’s personality: humility. Even though he was an extremely eloquent man and well versed in the Scriptures, he did not hesitate to place himself, like a child, in the school of those disciples. It is likely that Apollos was promptly baptized, perhaps by Aquila himself.

Regarding this attitude of Apollos, Msgr. Gaume reflects: “God blessed this disposition, as He always blesses humble souls.”2 In fact, Apollos was of enormous benefit to the community of Ephesus. However, he felt inspired to preach in another city, where one more group of Christians had been formed: Corinth.

In view of this impetus of grace, “the brethren encouraged him, and wrote to the disciples to receive him” (Acts 18:27). Apollos immediately departed for his destination, where great trials awaited him…

Fruitful apostolate in Corinth

Corinth was one of the most important cities in the Roman Empire. Located in the Isthmus connecting Peloponnese to the continent, it boasted two ports that provided it with bustling commercial activity. Scholars place the estimated number of its inhabitants between one and two hundred thousand!

This was a considerable population for that epoch.3 However, such prosperity, combined with the accentuated circulation of travellers, conspired to create an atmosphere of extreme moral degradation there. “Corinth was, so to speak, the capital of lust in the Mediterranean world.”4

Nevertheless, the Apostle St. Paul had founded one of his largest communities in that city, between the years 50 and 51, and had remained there for at least a year and a half (cf. Acts 18:11). Throughout this period, he faced harsh suffering and strong opposition from the Jews who lived there. His troubles reached such an extreme that Our Lord himself appeared to him to encourage him: “Do not be afraid, but speak and do not be silent; for I am with you, and no man shall attack you to harm you; for I have many people in this city” (Acts 18:9-10).

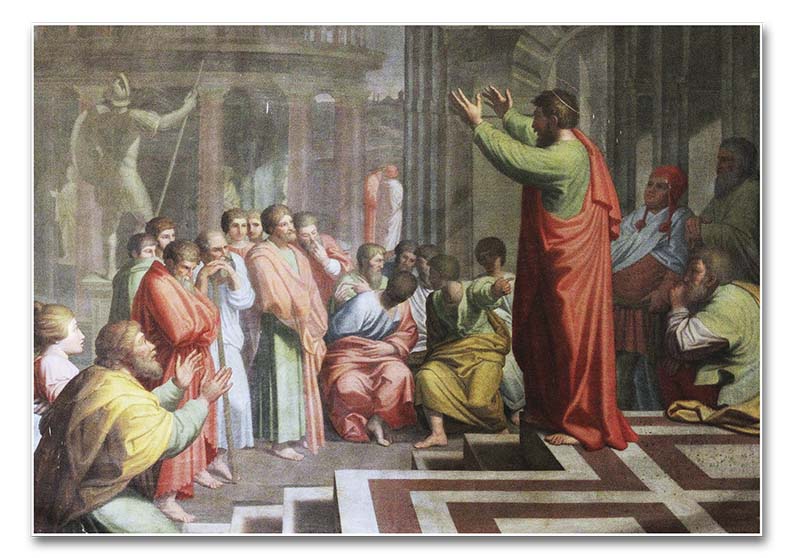

This was the setting that Apollos encountered, almost a year after St. Paul’s departure.5 However, none of this discouraged that dauntless preacher: “he greatly helped those who through grace had believed, for he powerfully confuted the Jews in public, showing by the Scriptures that the Christ was Jesus” (Acts 18:27-28).

Well-educated in the truths of the Gospel, Apollos preached in Corinth with the same success that he had achieved in Ephesus, becoming the Bishop of that city.6

Absurd dispute

In fact, his popularity among the faithful of Corinth grew to such an extent that it ended up bringing about a kind of division: some claimed to belong to Peter, others to Paul, others to Apollos, and still others to Christ…

This absurd attitude had several causes, the first of which was the superficiality of the Corinthians themselves. How could they have equated the Apostles with Our Lord, to the point where their authority was equal to His? It is not easy to come up with an answer.

The same superficiality led the Corinthians, upon seeing the great eloquence of Apollos, to consider him superior to St. Paul, who preached in a much simpler manner and without employing the resources of rhetoric (cf. 1 Cor 2:1-5).

As if this were not enough, we find an external factor: the creation of factions among the Corinthians was probably also inspired by certain “converted” Jews who arrived in the city shortly after Apollos and were looking for pretexts to attack St. Paul and his title of Apostle (cf. 2 Cor 10:9-10; 11:5-7; 12:11-13). The malice of these infiltrators is well expressed in the Second Letter to the Corinthians, in which they are called “false apostles, deceitful workmen, disguising themselves as apostles of Christ” (11:13).

It should be observed that Apollos was not at fault in the dispute that had developed. If there had been any bad intention in his apostolate, we can be sure that St. Paul – a man of a remarkably fiery, uncompromising and sincere character – would have censured him, as had been his approach even with St. Peter (cf. Gal 2:11). However, we see the opposite: all references to Apollos in the Pauline letters show great esteem and trust.

In any case, the parties were formed and the situation in Corinth became untenable. It was then that Apollos decided to leave the city to meet St. Paul in Ephesus.7

Encounter with St. Paul

Upon meeting with the Apostle, Apollos reported the entire division that the community of Corinth was suffering.8 His account was corroborated by that of several other disciples.

In view of this, St. Paul decides to write his First Letter to the Corinthians, in which, on the one hand, he rebukes them for creating factions and, on the other, he shows how Apollos was his collaborator in preaching the Gospel:

“For when one says, ‘I belong to Paul,’ and another, ‘I belong to Apollos,’ are you not merely men? What then is Apollos? What is Paul? Servants through whom you believed, as the Lord assigned to each. I planted, Apollos watered, but God gave the growth. So neither he who plants nor he who waters is anything, but only God who gives the growth” (3:4-7).

The Apostle’s humility, added to his desire to eliminate the divisions among the Corinthians, moves him to declare that his work was worth nothing. In fact, without the help of grace, no apostolate bears real fruit.

However, to be an instrument in God’s hands to proclaim the Gospel is an immense glory. Great as well is the glory of being a co-operator of the great Doctor of the Gentiles in his preaching. In this way, Apollos had the outstanding merit of watering the blessed seed that Paul had planted.

In another passage of the same letter, we find even more eloquent details: “As for our brother Apollos, I strongly urged him to visit you with the other brethren, but it was not at all his will to come now. He will come when he has opportunity” (16:12).

This passage shows, in the first place, the confidence that St. Paul had in Apollos. In the same letter in which he criticizes the division produced around his person, he states that he authorized Apollos’ visit to Corinth and, furthermore, strongly urged him to return. However, Apollos did not want to divert attention from what was most important: Our Lord Jesus Christ.

We can conclude that the Bishop of Corinth accepted with veneration the superiority of Paul, whom Our Lord himself had chosen to be the Apostle to the Gentiles. Apollos recognized himself as a mere instructor, whereas the father of the community of Corinth was St. Paul. This truth is also mentioned in the letter, shortly after the rebuke regarding the divisions (cf. 1 Cor 4:15-16).

And it is for these reasons that Apollos, as an example of humility, does not want to return to Corinth.

Once again immersed in mystery

After these episodes, the figure of the eloquent Alexandrian once again vanishes from sight. Did he return to Corinth together with St. Paul in the year 57? It is possible, but we do not have any documents that offer assurance on this point.

The next trace of Apollo appears only at a much later date, when the end of St. Paul’s life was approaching. It is the last mention of him in Holy Scripture, found in the Letter to Titus: “Do your best to speed Zenas the lawyer and Apollos on their way; see that they lack nothing” (3:13).

Titus was the first Bishop of Crete and, at the time, resided on that island.9 St. Paul writes to him to ensure that Apollos and Zenas – of the latter nothing else is known – are well supported on their journey. Once again, we see the Apostle’s esteem for his eloquent collaborator.

It seems that both Apollos and Zenas were with Paul at the time, and were to make some journey by way of Crete, perhaps back to Alexandria.10

And here, the ardent and eloquent preacher, disciple and assistant to the Apostle St. Paul, is once again immersed in mystery. Did he return once more to Corinth to care for his flock? Or did he, already advanced in years, stay until the end of his days in Alexandria? Why has he not been officially awarded the title of Saint by the Church?

Such questions remain unanswered for the time being…

However, the little we do know about this figure, whose name deserved to appear in the Sacred Books, already reveals to us an example of humility, unpretentiousness and faith, which the Holy Spirit wanted to grant the Church until the end of time. ◊

Notes

1 Cf. GAUME, Jean-Joseph. Biographies Évangéliques. Paris: Gaume e Cie, 1893, v.II, p.197.

2 Idem, ibidem.

3 This total only includes free men. It is estimated that there were also close to four hundred thousand slaves in Corinth (cf. LEAL, SJ, Juan et al. La Sagrada Escritura. Texto y comentario por profesores de la Compañía de Jesús. Nuevo Testamento. Hechos de los Apóstoles y Cartas de San Pablo. 2.ed. Madrid: BAC, 1965, v.II, p.330). The Bible of the University of Navarra speaks of one hundred thousand inhabitants, without mentioning slaves (cf. SAGRADA BIBLIA. Nuevo Testamento. Pamplona: EUNSA, 2004, p.963).

4 TURRADO, Lorenzo. Biblia Comentada. Hechos de los Apóstoles y Epístola a los Romanos. 2.ed. Madrid: BAC, 1975, v.VIa, p.183.

5 Cf. TURRADO, Lorenzo. Biblia Comentada. Epístolas paulinas. 2.ed. Madrid: BAC, 1975, v.VIb, p.3.

6 Cf. DIDYMUS THE BLIND. Fragments of the First Letter to the Corinthians. In: BRAY, Gerald (Dir.). La Biblia comentada por los Padres de la Iglesia. Nuevo Testamento. Madrid: Ciudad Nueva, 2001, v.VII, p.264. Although Didymus lived almost three centuries after Apollos, his testimony is of considerable importance because he was a native of Alexandria, and therefore his fellow countryman. Moreover, there are no statements in the New Testament or in Eusebius of Caesarea which contradict this fact.

7 It is impossible to establish the precise date on which Apollos left Corinth, however, his departure was not after the year 57, for it was in this year that St. Paul left Ephesus (cf. TURRADO, Biblia Comentada. Epístolas paulinas, op. cit., p.4-5).

8 Cf. Idem, p.5.

9 EUSEBIUS OF CAESAREA. Historia Eclesiástica. L.III, c.4, n.5. Madrid: BAC, 2008, p.124.

10 TURRADO, Biblia Comentada. Epístolas paulinas, op. cit., p.424.