We should all face life’s struggles with courage; but how can we practise this virtue if we do not understand what it involves?

The events currently shaking the world, such as the pandemic, natural disasters, political upheavals, armed conflicts, the crisis in Holy Church and even the questionable solutions presented by authorities to address these problems, elicit the most varied reactions among people. However, one common denominator can be detected in most of them: fear and, quite often, even panic…

In order not to give in to discouragement in the face of such a dismal scenario, we need to face life and its difficulties courageously. But what does it mean to be courageous? Before answering this question, it is necessary to understand what courage is not.

A false concept of courage

Most people have, at some point in their lives, come across a counterfeit product. The fact is that there are entire stores full of worthless objects that are very similar – in appearance – to high-quality ones. However, after a short period of use, they typically begin to disfunction, bringing only trouble and sometimes considerable loss to their owner…

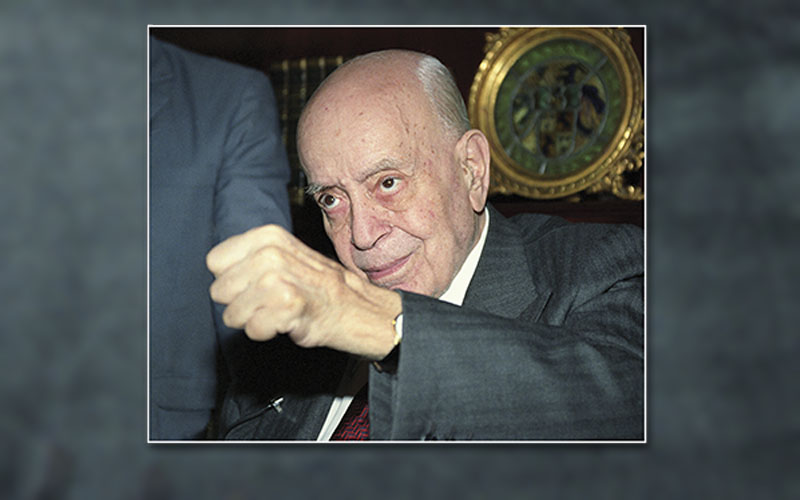

By an unfortunate coincidence, the same phenomenon occurs in the spiritual field: alongside authentic virtues, we find falsifications of them. And, as Dr. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira1 once pointed out, it is no different with courage. One of the greatest obstacles to its true practice is the diffusion of imitation varieties that are so often passed off as genuine…

Thus, in the soldier who faces death to defend his homeland we should recognize a hero; but a thief who runs the same risk in order to rob a bank is nothing more than a miserable bandit. Someone who defies danger, ready to sacrifice his life and reputation for the love of God is a martyr; but the impure man who puts his reputation and even his physical integrity at risk in order to clandestinely enter another’s house and consummate the destruction of the home, is no more than a wretched adulterer…

In these examples, the soldier and the martyr are truly courageous, while the robber and the adulterer, despite demonstrating apparent bravery, do not possess genuine courage. Indeed, if their homeland or their religion were to summon them to the field of sacrifice, they would not know how to immolate their selfishness for higher values. Therefore, to be courageous does not consist only in being willing to take risks; there is something more. What is it?

The main ingredient

Dr. Plinio gives us the answer: “Courage is, by definition, the disposition of soul, the virtue2 by which a man confronts great trials, suffering, hardship, grief and persecution for an ideal which he places above all else.”3

This, then, is what distinguishes the hero from the criminal. It is not enough to merely face great difficulties; one must overcome them for love of an ideal! Both the thief and the adulterer in our example were not moved by idealism, but only by selfishness…

Other falsifications

Moreover, Dr. Plinio alerts us that there are still other deformations of the virtue of courage. The first is the explosive temperament, by which the person becomes incapable of mastering his will. How many such situations do we witness in our daily life… How many pseudo-courageous people there are who confuse the outbursts of their own unbridled will with strength of soul. The difference between the latter and the truly courageous person is similar to that between a river that overflows its banks, flooding and destroying everything in its path, and the tranquil river waters that fertilize a region.

Another defect that seeks to disguise itself as courage is a clouded intellect, by which man does not perceive the danger that exists. Obviously, someone who is unaware of a risk easily faces it. However, it would be illusionary to imagine that such a person will achieve any lasting objective other than his own ruin. We have doubtless all seen an impetuous person set out to do great things, without measuring the risks or the consequences, and fail in all his undertakings.

How to practise this virtue?

So how do we practise true courage? First it is necessary to face dangers head-on and comprehend their magnitude; subsequently, to confront them by a deliberate act of the will.

We find characteristic examples of this virtue in the figure of the medieval knight. The Middle Ages, perhaps the most bellicose period in history, was filled with valiant warriors. However, it was also a time when men demonstrated a greater awareness of the arduousness and tragedy of war. It was for this reason that the military condition was so glorified; everyone understood the dangers to which combatants were subjected and, consequently, admired those who enthusiastically engaged in the arduous adventure.

Nevertheless, we must recognize that our sensibility will not always accompany the acts of our will. If on some occasions we feel true enthusiasm in practising the virtue of courage, on others we will experience fatigue and despondency of soul. At such times courage will be more meritorious!

Moreover, there will be times when we need to be courageous, not only deprived of a sensible impetus, but also having to fight against the grip of fear. Yes, the virtue of courage does not exclude fear; on the contrary, it must often be practised in defiance of it!

The Book of Judges tells the story of Gideon, a rather hesitant person (cf. Jgs 6). God appointed him general of His army and ordered him to advance against the enemy host of thirty-five thousand warriors, with only three hundred men, who were not to bear arms. He nevertheless obeyed, and the result was one of the most beautiful victories recorded in Holy Scripture.

Undoubtedly he practised the virtue of courage in all its splendour, but we would be mistaken to think that his sentiments always accompanied his will. Rather, he had to practise it despite his fear.

And what about my life?

At this juncture, it is possible that the reader is asking himself the following question: “All of this is true, but how do I apply such principles to my life? I am not a soldier, nor do I live in the Middle Ages or in the time of the Old Testament…” Nevertheless, while for the majority of people the difficulties of our days are of a very different nature than the examples narrated so far, the solution is the same.

When I must face the death of a relative, or the risk of losing my job, financial setbacks and illnesses, what should my attitude be? First, calmly look at the matter head on, considering all its dangers and the tragic consequences it may bring. Then, take the firm decision to face the problem in the right way, without the illusion that it will always be possible to avoid suffering. Often, on the contrary, the way to diminish suffering is to embrace the painful solution, if it is the most upright path.

But where can we find the strength of soul to take such a demanding attitude?

Catholic doctrine teaches us that no man will find within himself the means to practise the virtues perfectly and steadfastly. Courage being one of them, it is not surprising, then, that we should experience difficulty in cultivating it. The solution is to ask God to grant it to us, for He is the creator and source of all good.

The greatest act of courage in history

It would be a crime to end this article without mentioning the strongest and bravest Man of all time: Our Lord Jesus Christ. In the Garden of Olives, at the beginning of the Passion, what sentiments inundated His most perfect human Soul? Anguish, dread, sadness and the feeling of abandonment by those He loved most.

In this situation, our Redeemer did not take an unbalanced attitude that would be incompatible with His infinite holiness. He calmly contemplated all the suffering that He had yet to undergo, and this caused Him such fear that He even sweated blood! Then He practised the most supreme act of courage in history when He prayed to the Eternal Father, saying: “My Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from Me; nevertheless, not as I will, but as Thou wilt” (Mt 26:39).

Dr. Plinio explains this prayer of Our Lord in this way: “The height of courage lay in this: God has designs which, according to His infinite perfection, He sometimes withdraws, and at other times He does not. And in spite everything that caused utmost tension in Our Lord’s perfect instinct of conservation, He made up His mind: ‘I will go; I accept this! Thy will be done and not mine.’ That is the perfection of courage!”4

How different this attitude is from anything the world calls courage! The Courageous One felt weak, experienced fear, but looked at His cross directly, made the deliberate act of carrying out His mission and prayed for help. May this divine example, by which the Redeemer obtained graces for our correspondence in analogous situations, lead us to imitate Him to the full extent that may be required of us! ◊

Notes

1 Cf. CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, Plinio. Opera Omnia. Reedição de escritos, pronunciamento e obras. São Paulo: Retornarei, 2008, v.I, p.266. The present article is based on this publication of Dr. Plinio, in addition to two other expositions given by him, transcribed in: Uma era de fé, heroísmo e sabedoria [An Era of Faith, Heroism and Wisdom]. In: Dr. Plinio. São Paulo. Year IV. No.35 (Feb., 2001); p.18-23; O que é a coragem? [What is Courage?] In: Dr. Plinio. São Paulo. Year XVII. No.193 (Apr., 2014); p.8-9.

2 In the theology of St. Thomas Aquinas, the virtue that corresponds to Dr. Plinio’s concept regarding courage is fortitudo. This Latin word is commonly translated as fortitude; however, some prefer to use the word courage to better express its meaning (cf. PINSENT, Andrew. The Gifts and Fruits of the Holy Spirit. In: DAVIES, Brian; STUMP, Eleonore (Ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Aquinas. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012, p.477.

3 CORRÊA DE OLIVEIRA, O que é a coragem? [What is Courage?], op. cit., p.8.

4 Idem, ibidem.