F rom amidst the ruins of the once invincible Roman Empire, a light flickered in the shadows of nightfall. On Christmas Eve of 498, Clovis, King of the Franks, was preparing to receive Baptism. Seeing the sublimity of the sacred precinct, the awe-struck monarch asked the holy Bishop Remigius, “Father, is this Heaven?” As the water flowed over the head of the neophyte, not only did he receive Baptism, but France itself was also baptized, the first-born of Catholic nations, which, like a new star of Bethlehem, would lead a constellation of pagans to the Redeemer.

Later, kings such as Charlemagne and St. Louis IX proved that the spiritual and temporal spheres could – and should – be harmonious, and this was confirmed by the appeal of so many Pontiffs to make society sacral. Indeed, as Dr. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira demonstrated in his masterly essay Revolution and Counter-Revolution, Christian Civilization has an eminently sacral character, whose order can only be established by the observance of God’s Law.

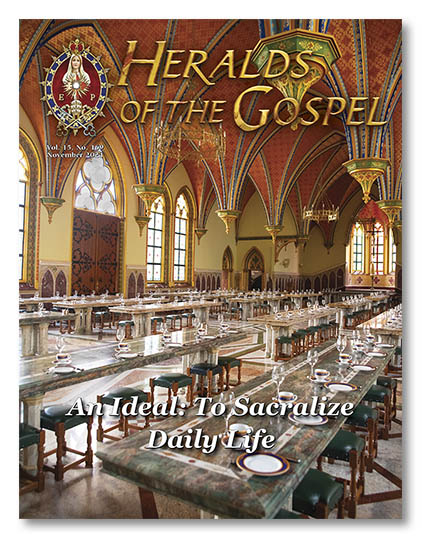

The Church is the Teacher of truth, goodness and beauty. For this reason, it has endeavoured to ensure that intellectual formation was always based on the foundation of the Supreme Truth. It pervaded the daily life of nations with examples of holiness and it reflected the beauty of the Divine Master in buildings, gestures, vestments, writings and ways of being.

However, it can be said that by the second half of the 20th century the “Heaven” of Clovis seemed to be obscured by clouds… Indeed, from that period onwards the Revolution marched at an even more rapid pace, with serious consequences for society in general and even for the Church itself.

In the field of tendencies, the inversions of values were multiple. For some ideologues, the Church now had to submit to the winds of the world and not the other way round. According to this viewpoint, under the pretext of drawing closer to the faithful, clerics ought to become secularized and religious buildings were to amalgamate with profane edifices. Culture, education and protocol, the typical and blessed fruits of Christian Civilization, were replaced by spontaneity, disorder and even vulgarity.

At the same time, in the field of ideas, a semantic revolution took place, with a clearly post-modern mentality. Neglect of the Liturgy was disguised under the pretence of simplicity; charity, called “the bond of perfection” (Col 3:14), was reduced to mere philanthropy; the magnificence of a church or the solemnity of a ceremony came to be considered empty ostentation and pomp; peace, once defined by St. Augustine as “the tranquillity of order”, metamorphosed into torpid and neglectful apathy in the face of the most absurd affronts to goodness, truth and beauty.

Nevertheless, the Apostle makes it clear that we must perform all of our actions for the greater glory of God (cf. 1 Cor 10:31). Otherwise, we will not only obscure Heaven, but we will also allow ourselves to be influenced by the fetid winds of hell. Therefore, during our earthly pilgrimage, we must aspire to the highest things (cf. Col 3:1), so that our lives may echo the words of Clovis at the dawn of Christian civilization: “Father, is this Heaven?” ◊