Carrying out the humblest task in the various monasteries in which he lived, he left a trail of joy wherever he went, for he loved God and his delight was being united to Him.

“Rejoice in the Lord, O you righteous” (Ps 32:1); “Happy are those whose way is blameless, who walk in the law of the Lord!” (Ps 119:1). These and many other teachings of the Psalms can be cited to show how virtue and true joy always go hand in hand.

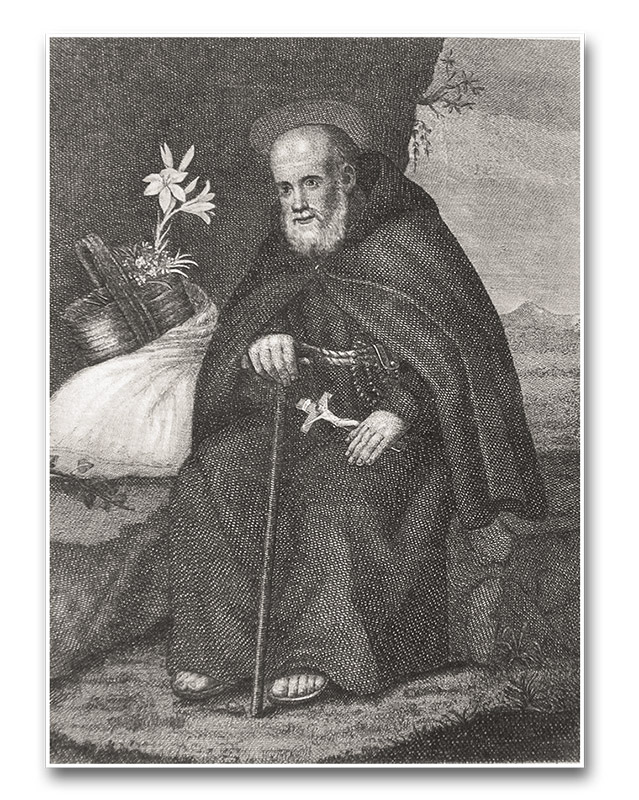

The intimate relationship between the two is especially apparent in the Saint whose life we will contemplate here: St. Crispin of Viterbo. In his homily at the canonization of this Capuchin lay brother of the seventeenth century, St. John Paul II rightly pointed out: “The first aspect of sanctity that I wish to note in St. Crispin is that of joy.”1

Consecrated from childhood to his “Mother and Mistress”

He came into the world on November 13, 1668, in Viterbo, a city then belonging to the Pontifical States. Two days later he was christened in the Church of St. John the Baptist, receiving the name Peter, after his grandfather. His parents, Ubaldo and Marzia Fioretti, were humble folk, but highly respected for their dignified and devout way of life.

While Peter was still a child, his father passed away, after entrusting the child’s education to his brother Francis. Marzia, for her part, made every effort to give him a thorough religious and moral formation.

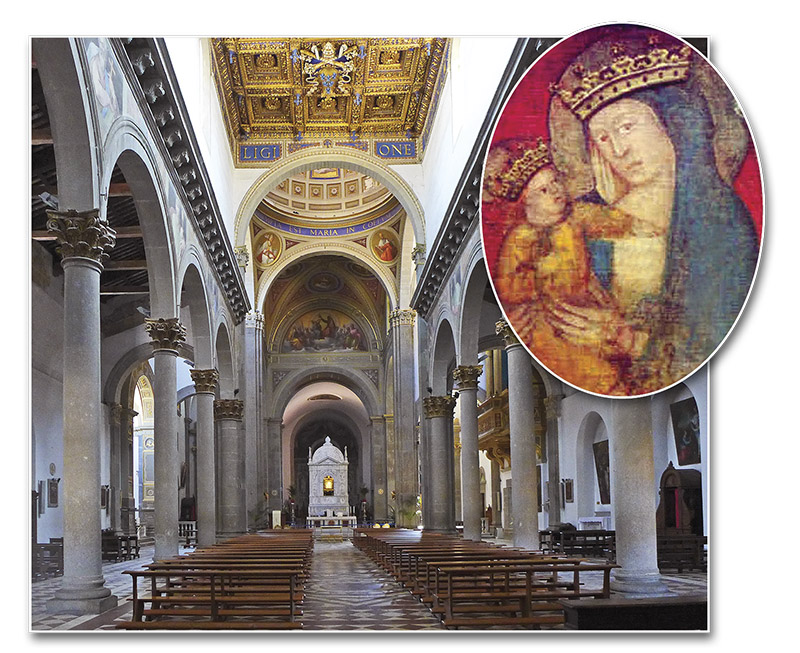

She took him on pilgrimage, when he was five years old, to the Shrine of Santa Maria della Quercia, to consecrate him to Our Lady. When they reached the shrine, the two knelt before the beautiful image and mother said to son: “Do you see? This is your Mother, and I now give you to her. Seek always to love her with your whole heart and to honour her as your Mistress.”2 These words sunk so deeply into the child’s soul that, until the end of his life, he never addressed the Blessed Virgin without calling her “Mother and Mistress.”

Better a scrawny saint than a stalwart sinner

One of his biographers comments that Peter, since his earliest childhood, demonstrated a markedly docile and agreeable temperament, accompanied by contagious joy, qualities that “proved the most favourable predispositions to progress along the paths of virtue and foretellers of his future holiness.”3

When he was a little older he accustomed himself to sacrifice and penance. He fasted on bread and water on Saturdays and on vigils of the feasts of Our Lady, even when he was sick—a practice that he continued as an adult. His uncle Francis noticed that the child was frail and poor of health and bluntly upbraided Marzia, saying that she was only good “to care for chickens, but not children, for Peter wasn’t growing because he wasn’t eating.”4 But his good mother made no reply, for she knew very well the reason behind the child’s weakness…

In his concern, the uncle began keeping an eye on Peter’s diet, and soon discovered that the problem was due to the lad’s spirit of sacrifice rather than a lack of food. He then apologized to his sister-in-law, with these words: “Let him be, for it is better to have a scrawny saint in the house than a stalwart sinner.”5

By ten years of age, he was serving as an altar boy at holy Mass and carrying out other duties of sacristan. At that same time, he went to study grammar with the Jesuit fathers and worked as a cobbler with his uncle Francis, a trade he practised until he was 25. He had the habit of using his earnings to buy the best and most beautiful flowers at the city market and place them at the feet of his “Mother and Mistress.”

“My mother, why do you weep?”

In 1693 a drought ravaged a large part of Italy. The inhabitants of Viterbo made a penitential procession to implore God’s mercy, and the young cobbler made a point of participating. Along the route he encountered some friars who wore a brown habit, who walked and prayed with angelic modesty and attention. They were sons of St. Francis of Assisi, and their virtuous demeanour awakened in the young man’s soul the desire to follow the religious life.

Certain of having found his vocation, he asked the provincial father to be accepted into one of the communities of the Order. After careful examination, the superior gave him a letter of admission and directed him to the novitiate in Palanzana. Peter showed the document to family and friends, saying: “Goodbye homeland, goodbye relatives, friends and all. Now I am a son of the Seraphic Patriarch and my place is among the Capuchin lay brothers.”6 His joy was so great that no one dared dissuade him from becoming a religious. Nevertheless, in vain they suggested to him another less austere Order, in which he could follow the path to priesthood.

Seeing his mother shedding tears of grief at his departure, he said to her with great respect: “My mother, why do you weep? Did you not consecrate me to God and the Blessed Virgin when I was only five years old? How could you now want to hold back what you gave? The donation was made freely and willingly, and with my assent. It is necessary, then, to resign yourself and honour it.”7

A frail young man in the austere Capuchin life

Filled with joy, he gathered his belongings and left for the novitiate, in the company of four other youths who were related to him. On the way, the devil tried to hinder him in various ways. At a specific point along the journey, a ferocious mastiff appeared, headed straight towards him. Without faltering, he called on the Blessed Virgin and the animal halted as if impeded by a powerful hand, and then slipped into a vineyard, disappearing from sight.

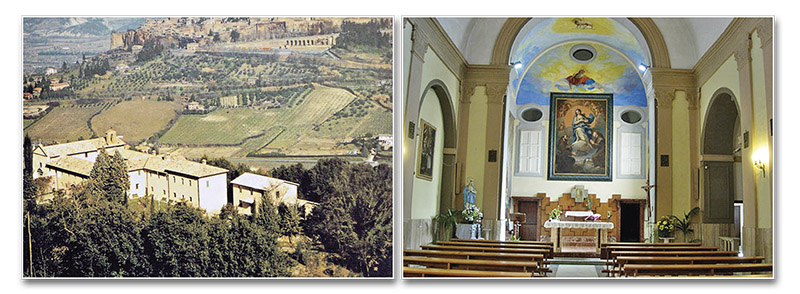

On July 4 of 1693, they arrived at the monastery of Palanzana. The Master of Novices, seeing Peter’s wasted physical condition, concluded that he was not in any state to endure the austerities of the Capuchin rule, and decided to reject him. Peter cast himself at his feet and implored to be received. Finally, after passing several tests, the young man obtained admission.

On the feast of St. Mary Magdalene, July 22, he was clothed in the habit of St. Francis, and following the custom of religious Orders, adopted a new name: Friar Crispin.

His first occupation was to care for the garden of the monastery, together with other lay brothers. Eagerly accepting the post, he worked for four or five hours in the sun, with greater effort and verve than the others, despite his poor physical constitution. Everyone was edified to see him carry out his duties, no matter how arduous, not only without complaint, but even with joy.

“Friar Swallow of the Lord”

Seeing how he had matured in the vocation, the master of novices gave him a new responsibility: to accompany the brother mendicant. In the exercise of this task, Friar Crispin demonstrated uncommon virtues and a remarkable evangelizing spirit.

Before leaving the monastery, he sang the hymn Ave Maris Stella and set out with rosary in hand. On the way, he catechized whoever he met, obtaining a true change of life in many people.

The young religious soon became known throughout the surrounding area. Many people flocked to him to give donations, requesting an even more valuable “alms” in exchange: that of his words and prayers. He responded to all with a peerless innocence, sometimes telling the person concerned to return a little later, for he needed to speak with his “Mother and Mistress” first.

The confidence he awakened in his interlocutors was so great that many left him with the certainty of having already obtained the grace desired. The piety of those whom he helped prompted them to snip pieces from his mantle to keep as relics.

On one occasion, a professed brother of marked goodness and simplicity noticed a swallows’ nest in a nook of the monastery and was enchanted to observe the joy with which the pair of birds brought food to their young. Associating this image to the joy with which Friar Crispin wore himself out supplying for the needs of his brothers in religion, he gave him the nickname “Friar Swallow of the Lord.”8

Trials and labours of the novitiate

In the midst of all his obligations, our Saint did not abandon his corporal penances and mortifications, in which he found supernatural strength to overcome the shortcomings of human nature. Now, as often happens, the devil took this opportunity to tempt him to discouragement.

The infernal enemy suggested to him that he did penance out of self-love and to avoid being expelled from the Order, and therefore, he was not motivated by love of God but by egoism. The trials were so burdensome that, while he never gave into sinful sadness, his countenance changed, reflecting his concern at the thought of displeasing Our Lord and His Most Holy Mother.

Perceiving the diabolical plot, the master of novices and his confessor gave him a formal order, in the name of holy obedience, to immediately reject these scruples coming from the devil. Friar Crispin obeyed and immediately recovered his peace of soul and a serene semblance.

All the novices took him as a model of religious perfection and fraternal charity. Even the master of novices would suggest to his charges: “Do as Friar Crispin does.”9

On one occasion, a friar was stricken with tuberculosis. Fearing contagion among the other brothers, the superiors decided to isolate him from the community. It being necessary to designate a good nurse, and aware of Friar Crispin’s charity and promptness, they assigned this responsibility to him. The young man dedicated himself with such love and care to the sick brother that the latter exclaimed: “This Friar Crispin is not a novice, but rather an Angel!”10

Fulfilling the humblest offices

Having made his perpetual profession, Friar Crispin set out for the monastery of Tolfa where he had been designated as cook. Upon his arrival, the atmosphere in the kitchen changed radically. He erected a small altar there with a statue of the Blessed Virgin, to whom he addressed continual prayers. He governed practical matters with the maxim of St. Bernard: poverty should never exclude cleanliness. All those who entered this area were edified with the order and efficiency that reigned in such a prosaic part of the monastery.

During his fifty years of religious life, the Saint spent time in a number monasteries: Monterotondo, Rome, Albano and Orvieto. In each one, he carried out modest duties with remarkable humility and unpretentiousness. Whatever task he was given, joy and the supernatural spirit never left him. He worked more than a few miracles during his lifetime, such as the cure of several sick people in an epidemic that swept through Italy, by simply touching them or tracing the Sign of the Cross upon them with his medal of Our Lady.

Prelates, nobles, and learned men sought him out to beseech a cure from the plague or just to observe the good odour of sanctity that he exuded. Cardinal de Tremoglie, Minister of France, was cured of a serious illness by eating a special funghi that the Saint gave him, after presenting it to Mary Most Holy for this purpose. Even Pope Clement XI took delight in conversing with him and sought him out in Albano, when he was living there.

The peace and joy of a good conscience

In 1750, although with seriously compromised health and bedridden, his customary joy did not leave him. Having returned from the monastery of Rome and not wanting to disturb the celebration of the memorial of St. Felix of Cantalice—a Capuchin of his devotion canonized a few decades prior—Crispin declared to the nurse that he would only die after the two days dedicated to his memorial at that time: May 17 and 18. And that is, in fact, what happened: the Lord took him on May 19, at 82 years of age.

A multitude flocked to his funeral. Everyone implored graces or sought to obtain a relic. The miracles were not long in coming. In the heart of many of his devotees, there undoubtedly resounded a phrase which he repeated when he was asked to define holiness: “Those who love God with purity of heart live happily and die content.”11

This phrase sums up his entire life!

In fact, only those who fulfil their own mission are capable of experiencing true joy, for they are at peace with God. They carry in their soul, as Msgr. João Scognamiglio Clá Dias teaches, “true peace, that of the well-ordered conscience of a person who practices virtue and shuns sin.”12 ◊