The meaning of the name Hedwig indicates a woman destined for “combat and victory.” A duchess of fine features and delicate bearing, she lived up to this signification, for she took up the struggle of resignation in the face of God’s designs and bravely faced the sufferings that devastated her country, which is why she was called the “strong woman of the Gospel.”

A flower of European nobility

Hedwig was the second daughter of Berthold IV, Count of Andechs, Merania and Tyrol, and Agnes, daughter of Count Rotlech, Margrave of the Holy Empire, whose genealogy can be traced back to Charlemagne himself.

The couple had six other children, including Agnes, who married Philip Augustus, king of France, and Gertrude, who married Andrew, father of St. Elizabeth of Hungary and king of that nation. These marriages afforded Hedwig relations with several of the European royal houses.

A childhood pervaded with innocence and chastity

It is not known on exactly what day Hedwig was born in 1174. A child of an extremely affable, but serious and noble character, from her cradle she showed a marked inclination to innocence and chastity, qualities so scarce in the ostentatious circles of the court and which she would preserve all her life.

On reaching the age of six, she was entrusted to the care of the Benedictine nuns of the Abbey of Kitzingen in order to acquire the religious and cultural knowledge that her condition demanded. The nuns soon noticed in the girl a penetrating intelligence as well as numerous gifts: she was skilful in in the art of illumination and embroidery, as well as singing and playing various instruments. During the time spent in the convent, she also studied Sacred Scripture, devoted herself to caring for the sick and learned to organize gardens and vegetable plots. However, her soul found its true delight in spending long hours in the church or at the foot of some statue of Our Lady.

Virginity of soul in marriage

By twelve years of age, she had already acquired an exemplary maturity. The nobility of her blood, her beauty and her luminous intelligence made her hand very coveted for marriage. However, her greatest desire was to remain a virgin and to consecrate herself entirely to God.

Nevertheless, the designs of Providence are mysterious and inscrutable! Through her marriage to Prince Henry I of Silesia, the Lord united in Hedwig’s soul two qualities that seem contradictory to the eyes of the world: virginity of soul and motherhood.

Although a devoted wife and a very affectionate mother, she preserved intact the purity of her soul, as if she had never been bound to anyone by human ties, living continually for God. She had learned from the Divine Master the key to loving creatures with a pure and supernatural affection, which allowed her to preserve her chastity of heart until the end of her life.

Forming the image of Christ in her husband’s soul

With her marriage, she left her parents’ palace in Germany and went to live with Henry in Silesia, a region of medieval Poland.

This was a very brusque change for the young woman. Poland at that time was still emerging from barbarism and the customs of the people were very crude, as compared with those of her homeland. She had to fortify her heart to face the sufferings of her new condition, with such results that she was considered “the first German princess who managed to adapt to the inhospitable soil of Poland.”1 In short order, she captivated both nobles and servants by the sweetness and uprightness with which she treated them.

Her first mission was to understand her husband’s temperament in order to better serve him, and she was so successful in this endeavour that she won his heart completely.

Henry was courageous, strict with himself and generous, but his religious education left much to be desired. Hedwig, who loved him as much as possible on this earth, was especially concerned for his soul. She became his catechist and tutor, teaching him the practice of prayer and good morals. With each passing day, Henry had more reason to trust his holy wife, and his heart was gradually led to God by her love and devotion.

Vow of perfect chastity

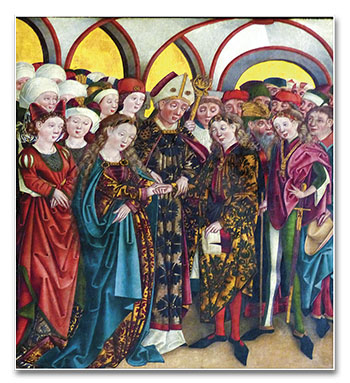

The marriage of Hedwig was blessed with fruit, for she bore six children. After the last of these was born, she and Henry took a vow of perfect chastity, sealing this promise secretly in the hands of a bishop. When the fact became public, they decided to live in separate residences in order to avoid scandal, and from then on they always met in the company of witnesses.

Hedwig moved to a monastery of Cistercian nuns that her husband had built in Trebnitz, present-day Germany. Henry, drawn by his wife’s example, began to lead a religious life while still in the world. He cut his hair in the form of a tonsure and grew a beard;2 he acquired such deep humility and ardent devotion that he was considered a Saint.

With great admiration the people could see a young princess, full of gifts and esteemed by all, living more as a religious than as a noblewoman. The maxim of her life was that the more illustrious one’s origin, the more it was necessary to distinguish oneself through virtue; the higher the social position, the greater the obligation to edify one’s neighbour through good example. And this she carried out to perfection.

Patroness of the destitute, the poor and those in debt

In the new life she had undertaken, Hedwig decided not to take a vow of poverty for a very definite reason: to continue helping others with her goods. She was very rich, but lived on a minimum income for herself; with the remainder she helped the poor and built hospitals, schools, churches and monasteries. On account of countless acts of charity that have endured the centuries, she is considered the patron Saint of the underprivileged, the poor and those in debt.

However, perhaps her greatest work of mercy was to employ her power and political influence to favour the growth of the Church and save souls. The religious state of the people and even of many of the clergy was at that time truly lamentable. Hedwig was undaunted: she undertook bold ventures, spent her fortune and exhorted the clergy, with the goal of seeing the true Catholic doctrine shine in the souls of all her subjects. For this reason, she is often represented with her crown over the Holy Scriptures, signifying that her power and wealth were founded on the Faith; or with a church in her hands, due to her concern to protect and expand the domain of the Mystical Bride of Christ.

Magnanimity and fortitude in the face of misfortunes

“Hedwig knew that those living stones that were to be placed in the building of the heavenly Jerusalem had to be smoothed out by buffetings and pressures in this world, and that many tribulations would be needed before she could cross over into the glory of her heavenly homeland.”3 Indeed, St. Hedwig had discovered the secret that lies behind the Cross! And she did not waver in the face of the pain and sacrifices that God asked of her.

A series of calamities befell this noble soul. In 1237, her son Konrad died after being attacked during a hunt by a wild beast. During the same period, while still immersed in sorrow, she mourned the death of another son, Boleslaw.

As if that were not enough, her husband fell prisoner to Prince Konrad of Plock during the war. Full of courage, she personally appeared before the latter to obtain her husband’s release. Konrad had never allowed himself to be intimidated by anyone, “but when he saw the Duchess Hedwig before him, the man trembled. It seemed to him that an Angel stood before him, threatening him. Without demanding a ransom he set the prisoner free.”4

A short time later, Henry set out for the region of Krosna, Poland, but seized by a sudden illness, he died in 1238. The nuns of the abbey of Trebnitz were shaken by the news of the ruler’s passing. The only one who remained serene was Hedwig, who tried to comfort the others: “Why do you complain about God’s will? Our lives are in His hands, and everything He does is well done, even when it is a matter of our own death, or the death of our loved ones.”5

A holy penitent with a wealth of gifts

St. Hedwig had extremely austere habits. She usually lived on bread and water or ate only a few boiled vegetables; for forty years she abstained from meat. After her death, her daughter-in-law Anne testified before ecclesiastical authorities that, “of all the lives of penitent Saints she had read, she had never come across anyone who surpassed her mother-in-law in penance.”6

She used to walk barefoot to church, even in the snow. But as she did not like others to see her sacrifice, she always carried her shoes and put them on when anyone came into view. One day a maidservant who was accompanying her began to complain about the cold. Hedwig then told her to place her feet in her footprints. The woman began to feel a great warmth that invaded her whole body.

Providence had endowed the soul of this generous lady with countless favours, among them the gift of prophecy and the revelation of hidden things, which made her aware of events taking place at a great distance. She foresaw wars and calamities that would ravage her country; she cured the blind and those afflicted with other maladies. She was often found in a state of deep ecstasy, surrounded by a light so strong that it dazzled those who witnessed the phenomenon.

Intimate union with Our Lord Jesus Christ

St. Hedwig always kept the mystery of her intimate union with the Lord from becoming known. However, such was the fervour that pervaded her that she could not repress the sighs, “cries of love and songs of joy that escaped her heart to greet her Divine Bridegroom.”7

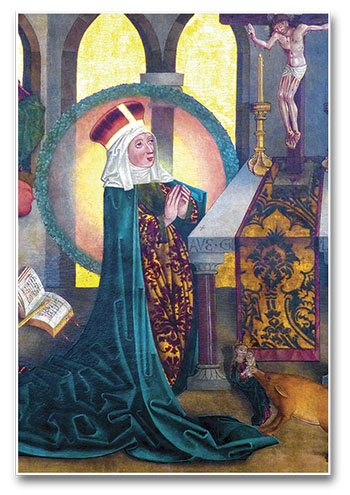

A certain nun, desirous of knowing what she did in the church when she remained there alone for long hours, once hid herself in the choir. From there she witnessed an admirable scene: after having kissed each of the seats used by the nuns for the singing of the Office, she knelt before the altar of the Blessed Virgin, above which was a crucifix, and remained there with her arms open in the form of a cross. As she prayed thus, the arm of Christ detached itself from the cross and He blessed her, saying: “Your prayer has been heard, you will obtain the grace you ask of Me.”8 Thus she won the Heart of God with her love and prayers.

Battle against the demons

To prove her fidelity and love to her heavenly Spouse, she had to be exposed to a terrible ordeal. Demons appeared to her in horrible forms and beat her, repeating in a furious voice, “Why are you so holy?” In those moments she was mysteriously robbed of her strength and immersed in darkness and abandonment. The gates of the abyss opened before the duchess and the most harrowing temptations presented themselves. All the passions which she had repelled over the years assaulted her spirit: anger, hatred, envy… If she did not know that an invisible hand was supporting her, she would have despaired. However, Hedwig endured everything patiently. When the time of trial was over, that same divine hand lifted her up, leading her back into the kingdom of light.

As the day of her death drew near, the Lord gave her a foretaste of the happiness of Paradise as a reward for her fidelity during the assaults of hell: many citizens of the heavenly Jerusalem came to visit her. On the day of the Blessed Virgin’s nativity, Catherine, her faithful servant, witnessed a wonderful scene: she saw several of the blessed entering her room. Full of joy, she greeted them: “Dear Saints, welcome! St. Mary Magdalene, St. Catherine, St. Thecla, St. Ursula!”9

Death and canonization

At last, the hour struck for Hedwig to surrender her soul to God. It was October 15, 1243. On the bed where she lay, from time to time she opened her blue eyes to raise them to Heaven and pronounce the divine name of Jesus. While the sisters intoned the Psalms, she looked up to Heaven once again and, without a gasp, she breathed her last in this valley of tears. Her remains were then besieged by the nuns: some cut her nails, others her hair, while others took pieces of her clothing.

At last, the hour struck for Hedwig to surrender her soul to God. It was October 15, 1243. On the bed where she lay, from time to time she opened her blue eyes to raise them to Heaven and pronounce the divine name of Jesus. While the sisters intoned the Psalms, she looked up to Heaven once again and, without a gasp, she breathed her last in this valley of tears. Her remains were then besieged by the nuns: some cut her nails, others her hair, while others took pieces of her clothing.

The Polish people long mourned the loss of their mother. But she would not abandon those whom she had loved so much on earth. Miracles ensued, followed by more miracles.

On October 15, 1267, just twenty-four years after her death, Pope Clement IV, who himself had obtained a miracle through her intercession, inscribed her in the catalogue of the Saints. ◊

Notes

1 KNOBLICH, August. Histoire de Sainte Edwige. Duchesse de Silésie et de Pologne. Tournai: H. Casterman, 1863, p.37.

2 For this reason, until today he is known as Henry I the Bearded.

3 FROM THE LIFE OF ST. HEDWIG. By a contemporary author. In: INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON ENGLISH IN THE LITURGY. The Liturgy of the Hours. New York: Catholic Book Publishing Co., 1975, v.IV, p.1485.

4 MONTANHESE, Ivo. Vida de Santa Edwiges. 24.ed. Aparecida: Santuário, 2012, p.37.

5 BUTLER, Alban. Vida de los Santos. Cidade do México: Collier’s International, 1965, v.IV, p.127-128.

6 MONTANHESE, op. cit., p.71.

7 KNOBLICH, op. cit., p.230.

8 Idem, p.231.

9 Idem, p.280.