Slowly, deeply, and solemnly, the bells of the Church of the Holy Cross of Jerusalem, the most important in Seville, announced the departure from this world of Archbishop Isidore, admirable for his knowledge, his writings and, most especially for his upright life. It was April 4, 636. Clothed in episcopal insignia, the Holy Gospels resting upon his breast, his body lay in state in the presbytery while the people mournfully crowded in to pay their filial homage. He was then taken to his final resting place, the Church of St. Vincent, and buried between Leander and Florentina, his siblings by blood and sanctity.

Who was this man, of such blessed stock, and whose death was so keenly felt?

Barbarian hordes invade the Empire

From the dawn of the fourth century, and with greater intensity over the course of the fifth century, the once-powerful Roman Empire was gradually rendered incapable of deterring the advance of the barbarian hordes which flowed into its territory on every side, sacking, burning, and destroying everything in their path. Believing culture to be the cause of the decadence of that formerly warlike people, the barbarians were bent on destroying all the books they could lay their hands on.

However, worse than material destruction were the obstacles set in place by the pagan and Arian invaders to the development of the Catholic Church which had recently obtained freedom to act, granted by the Edict of Milan, in 313, by the Emperor Constantine.

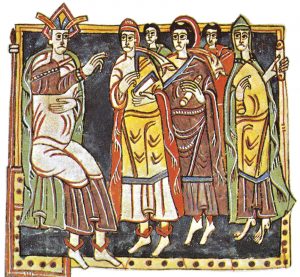

The barbarian peoples were given to internal feuds in the conquest or in the maintenance of particular territories. This played out in the Iberian Peninsula, the object of dispute among the Alani, Suevi, Vandals, and Visigoths. The latter, allied to Rome, eventually triumphed and kept the region under their dominion.

Foundations in the formation of a wise man

Isidore was born in this turbulent time around the year 556, into a noble Gothic family. His father, Severianus, was Catholic and, due to the Byzantine invasion, had migrated with his kin from Cartagena to Seville, where our Saint was born. Historical records reveal that his mother, who followed the Arian sect in Cartagena, embraced the Catholic Faith upon arrival in Seville. At that time, the couple had three children: Leander, an adolescent, who had received the customary education afforded to noble Christian Goths of that time; Fulgentius, still a boy, and Florentina, a young child. They, along with Isidore, were raised to the honour of the altars and became known as the Four Saints of Cartagena.

Isidore was almost six years of age when they were orphaned. His brother Leander, taking the death of their parents as a call to abandon the fleeting goods of this world and dedicate himself exclusively to God, used the paternal inheritance for the founding of two monasteries: one for women, in which his sister Florentina was consecrated, and one for men, of which he became abbot.

As the immediate consequence of the barbarian invasions, the cultural foundation of Greco-Roman civilization was almost extinguished in the lands of present-day Europe. The monasteries remained as faithful depositories of the literary works produced over the centuries, as well as the marvels of Revelation. An example of this was the monastery in which Abbot Leander opened a school to teach youths the elementary subjects such as arithmetic and grammar, as well as geometry, music, rhetoric, dialectics and even astronomy. Young Isidore began his studies there under his brother’s tutelage, laying the foundations upon which his exceptional intelligence developed, so as to later render great service to the Church.

From student to master of souls

When he was about 20 years of age, his brother Leander was acclaimed Archbishop of Seville and was soon thereafter appointed councillor to the Visigoth king Reccared, a Christian convert. Inspired by his brother’s resolve, Isidore took the religious habit and, in 589, was a newly ordained priest. His youth did not prevent him from succeeding Leander as abbot of the monastery: holiness conferred on him the necessary prudence and maturity for the direction of souls.

Unfortunately, however, the state of Spanish monasticism was none too encouraging: in addition to the inevitable effects of barbarism, many Christians embraced religious life for prestige instead of for love of God and the desire for sanctity. Many others, devoid of the willingness to sacrifice themselves for their confreres, drifted apart from communal life.

Far from becoming discouraged or making peace with this decadence, St. Isidore set about writing the Regula monachorum and, with no less ardour, undertook the reform of his monastery, seeking to uphold it as a beacon for religious life on the Iberian Peninsula. In this undertaking, he rooted himself in the teaching of the Divine Master—“If any man would come after Me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow Me” (Mt 16:24)—, instituting as the main point on the path to perfection the “renunciation of oneself so as to put on Christ, the practice of abnegation, poverty, humility, work and prayer.”1

Prayer and intellectual work

On one hand, he set the interior life above fasting and corporeal mortification, given that the sacrifice of self-will pleases God more than any other penance. On the other, he did not neglect work, a vital part of monastic daily life. Ora et labora was the motto of St. Benedict, father of Western monasticism.

The rule of St. Isidore united manual labour and intellectual work, emphasizing that study is a duty of religious. In this way, he motivated his monks to value reading, especially Sacred Scripture, recommending that this be followed by meditation. In his Third Book of Sentences he wrote: “Every advantage comes to us from reading and meditation, for with reading we learn things of which were ignorant, and with meditation we guard what we have learned.”2

He further determined that the monks should copy classical works to spread them among the other monasteries. For hours on end, some would dictate while others transcribed. He also prescribed norms regarding the practice of charity among the brothers. For example, every night, when the last prayer in common ended, all would mutually pardon one another and then receive absolution from the abbot. And if one brother saw another commit a fault, he was to give him a fraternal correction.

The Isidorian rule is one of the first that did not prescribe corporeal punishments, while it nevertheless upheld the need for salutary correctives: guilty monks were punished with privation from community conviviality, which would last a few days, several months or even a year, depending on the gravity of the fault.

As a good spiritual father, St. Isidore duly established norms concerning the regulation of points of daily life, such as the monks’ repose: if possible, all were to sleep in one room, with the bed of the abbot placed in the centre. His presence among them and the testimony of his holy life were a “homage to discipline.”3 He also ordained that the religious habit should be poor and modest, but not miserable, “so as neither to produce sadness in the heart, nor a reason for pride.”4

Broad culture at the service of sanctity

The holy abbot would not have attained success in his reform had he not personified what he preached. In fact, he was a constant model of abnegation in his concern for others rather than with self. As for intellectual endeavours, he devoted himself to writing several works which have come down to us. His main achievement, Etymologies, is a compendium of the branches of science of that time and took twenty years to complete. In this and his other works, the Saint reveals consummate ability to compile and organize extant knowledge and doctrine.

A man of broad culture, St. Isidore was fluent in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, and was an expert on the classical authors. In addition to his office of abbot and duty as writer, he distinguished himself as a professor. The School of Seville, which he directed became famous throughout the Iberian Peninsula. Illustrious ecclesiastics, including St. Braulio, Bishop of Zaragoza, and St. Ildephonsus, Bishop of Toledo, were formed there, as well as young men from high nobility, among whom the kings Sisenand and Sisebut stand out. The latter would help him to consolidate Christianity in nascent Spain.

St. Isidore maintained enduring bonds with his former students, dedicating some works to them: the Etymologies, to St. Braulio, and De natura rerum, to King Sisebut. “Isidore to his lord and son Sisebut,”5 was his inscription, describing the friendship that united them.

Archbishop of Seville

St. Isidore’s efforts bore fruit, and a new spiritual and intellectual order reigned in both monastery and school. But God would demand more than a quiet cloistered existence of his servant. Around the year 600, his brother St. Leander died after a turbulent and heroic life crowned with the conversion of Visigothic Spain to Catholicism. Encouraged by the authorities, the people acclaimed Abbot Isidore Archbishop, at 43 years of age.

His fervour, wisdom, and majestic bearing marked his preaching and soon attracted multitudes from near and far. Along with his concern for the people, the new Archbishop was a zealous former of priests, encouraging them to progress along the path of holiness. He took special care with the seminarians, seeking to imbue them with dignity and seriousness in their deportment—not with an eye to ostentation, but because good conduct should be the reflection a virtuous soul.

Accordingly, the holy Archbishop required of his clerics perfection in external acts in addition to spiritual perfection: “Demonstrate what you profess in your conduct and dress. Have simplicity of manner, purity of movements, gravity in your gestures and honesty in your footsteps. For the soul is seen in the semblance of the body; the posture of the body is an image of the mind, through it the soul manifests itself and the inclinations are revealed. Therefore, avoid levity in your conduct; do not harm the gaze of others with it.”6

With even greater striving, St. Isidore promoted the greatest possible splendour of the Liturgy. He introduced sacred music to the liturgical acts, and even composed several hymns. He counselled his clerics to pray the Divine Office as the monks did.

When Sisebut ascended the throne in 612 our Saint’s influence had attained its apex, and he used the circumstances to advantage, solidifying the rights of the Church in the kingdom. Despite the tie of friendship that united him to the king, Isidore was firm in admonishing him when he meddled in ecclesiastical affairs. On one occasion, Sisebut was upbraided in these terms by his former teacher: “An apostolic precept prohibits lay persons from being admitted into the government of the Church.”7

He fought the good fight; he received the crown of righteousness

He rendered innumerable services to the Church during this period. With marked organizational capacity, St. Isidore unified the liturgical rubrics throughout the kingdom and created the Collectio Canonum Ecclesiæ Hispanæ, a complete compilation of conciliar decrees and canons which governed the Spanish Church until the Gregorian reform.

As he approached his eighties, he was called to preside over the Fourth Council of Toledo, in which important norms regulating the relationships between Church and State were drawn up. When the assembly closed, Archbishop Isidore felt that the time had arrived for him to proclaim, like St. Paul: “I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith” (2 Tim 4:7). There only remained for him to receive from the just Judge the “crown of righteousness” (2 Tim 4:8).

On March 31, 636, accompanied by his two suffragan bishops, he went to the Basilica of St. Vincent to fulfil the preparatory rite for death, according to the custom of the time. He prostrated before the altar, clothed in sackcloth. Moved by profound humility, he did public penance for his sins, asking pardon to the faithful for his possible bad examples and gave his last counsels to the multitude, who looked upon heir Shepherd for the last time. Four days later, his holy soul ascended to Heaven.

Along with his brother St. Leander, St. Isidore was inscribed in the roll of the Fathers of the Church, closing the list of the Latin Fathers. A few years after his death, the Eighth Council of Toledo praised him with these immortal words: “Magnificent Doctor, glory of the Catholic Church, the wisest man to come to enlighten recent ages, whose name should be pronounced with great respect.”8 ◊

Notes

1 QUILES, SJ, Ismael. San Isidoro de Sevilla. Buenos Aires: Espasa-Calpe, 1945, p.29-30.

2 ST. ISIDORE OF SEVILLE. Sentencias. L.III, c.8, n.3. In: ROCA MELIÁ, Ismael (Ed.). Los tres libros de las “Sentencias”. Madrid: BAC, 2009, p.147.

3 ST. ISIDORE OF SEVILLE. Regula monachorum, c.XIII, n.1: ML 83, 883.

4 Idem, c.XII, n.1, 881-882.

5 ST. ISIDORE OF SEVILLE. De natura rerum. Præfatio: ML 83, 963.

6 ST. ISIDORE OF SEVILLE. Synonyma. De lamentatione animæ peccatricis. L.II, n.43: ML 83, 855.

7 ST. ISIDORE OF SEVILLE. De officiis ecclesiasticis, apud QUILES, op. cit., p.37.

8 EIGHTH COUNCIL OF TOLEDO. Canon II. In: MANSI, Joannes Dominicus. Sacrorum Conciliorum. Nova et amplissima collectio, ab anno DXC usque ad annum DCLIII, inclusive. Florentiæ: Antonii Zatta Veneti, 1764, t.X, col.1215.