Called to keep the torch of Carmel alight, she revived the legacy of the “Foundations” in the twentieth century, in the purest Teresian style. Her driving force was letting herself be led by the divine will.

From its distant origins to modern times, the Order of Carmel has always enriched the Church with great Saints. We might ask which souls were the key representatives, in our age, of this charism that is venerable under so many titles – riddled with persecution yet all the while so clearly and constantly favoured by Divine Providence.

In other words, who could be identified in the twentieth century as one, who, in our wayward world, was, like the Prophet Elijah, Father of Carmel, consumed with zeal for the glory of God (cf. 1 Kgs 19:10) and for the salvation of souls – the essence of the Carmelite mission?

The Discalced Carmel of Spain, fruit of the reforming zeal of St. Teresa of Avila and St. John of the Cross, offers a possible answer.

Vocation to make reparation for the outraged glory of God

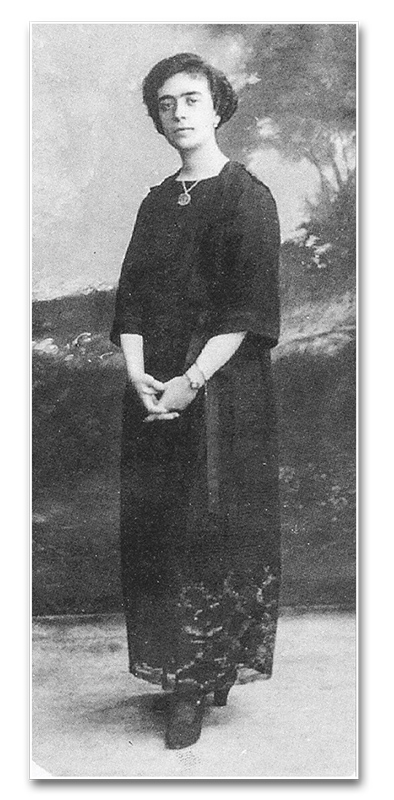

At the close of 1919, a Madrid woman of 28 years entered the silent cloister of the Discalced Carmelites of San Lorenzo de El Escorial. At the beginning of her life of observance she expressed her gratitude to God for her vocation: “I cannot but thank Thee infinitely that this was Thy will in my regard.”1

Her name, Maravillas de Jesus, habitually awakened curiosity in those who heard it for the first time. But her superiors decided that she should continue to be called by this name when she was received into the novitiate, even despite her expressed desire to change her baptismal name2 for a simpler one, in keeping with her resolutions to embrace the religious life: “All that is sought in Carmel is to disappear so that the Lord may reign.”3

Decades later, when the influx of people who wished to make her acquaintance became notable, St. Maravillas would attribute this interest, which she found exaggerated, to her name: “If I were called Maria, no one would pay any attention to me”…4 Nevertheless, the faithful, attracted by her holiness, were convinced that this name suited her very well for higher reasons: God ceaselessly worked marvels through her.

With utter detachment from her illustrious origin and sizeable fortune, the fourth daughter of the Marquis of Pidal aspired, from a young age, to give herself entirely to the contemplative way. Her father sought to persuade her that she could also work for the Church in the world. Her mother, in turn, would not hear of the girl leaving her side, especially after her husband passed away. However, the noblewoman finally came to acknowledge that her daughter would never adapt to the opulent life of Spanish high society, something that Maravillas herself confessed after several years of cloistered life: “As for me, I am happier with each passing day in the convent, and give thanks to God that He gave me the Carmelite vocation, the best thing in the world.”5

Having obtained her mother’s permission, she chose to enter the Carmel of El Escorial, where the prioress would put her to the test. For, as this superior affirmed, it was easy to undertake good works in the world, where one receives applause and praise for doing one’s own will; however, under the regime of obedience the true dispositions of the heart are revealed: “Here everything is revealed under the light of truth.” Far from intimidating the novice, this expression was received as a sign that God wished to sanctify her in that monastery.

The prolonged period during which Maria das Maravillas Pidal had remained in the world would serve to solidify her vocation, allowing her to witness first-hand the moral decadence of the years leading up to the Second World War. Her lucid intelligence, assisted by grace, prompted her to discern a wave of iniquity rising up from the earth, in face of which there were few who took upon themselves the vitally important task of making reparation for the glory of God outraged by the grave sins being committed.

From the outset and without reserve, she resolutely dedicated herself to her great goal in life: to give to Our Lord Jesus Christ, in Carmel, the homage of adoration that was denied to Him everywhere. “There are so few souls who give themselves entirely and with complete confidence to Him, always believing in His love and letting Him do what He wishes in us and with us, that when He finds some such souls I believe that it will be a great joy for His most affectionate Heart that loves us so.”6

Votive light of praise before the Sacred Heart of Jesus

Due to her already advanced degree of virtue, it was not long before the new Carmelite became a joy for the convent. When the cloister grill closed behind her, she believed she was making her definitive break with the commotion of the world. Nevertheless, events would soon take a turn: even before professing her solemn vows, a series of unequivocal signs began to indicate that Providence was calling her to found a new convent, despite the fact that she was only four years into religious life.

This bold step was occasioned by the general abandonment of the monument to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, erected by King Alfonso XIII on the small hill marking the geographical centre of the Iberian Peninsula, the Cerro de los Ángeles [the Hill of the Angels]. Its construction had involved the combined effort of many Spaniards, but soon after the work’s inauguration and the country’s consecration to its King and Lord in 1919, the site had reverted to its former state of oblivion. The symbolic importance of the act had failed to awaken a groundswell of devotion.

The rapid waning of popular piety incited the reaction of fervent hearts who saw the need to fill that void. The inspirations of several people and particularly that of Sr. Maravillas pointed to the founding of a contemplative convent at the site, with the prime mission of keeping the Sacred Heart of Jesus company “day and night, in the place chosen by Him to reign in our poor Spain, despite His enemies.”7

The idea was set in motion and after three years the result was the magnificent Carmel beside the monument, of which St. Maravillas would be prioress.

Miraculous protection during the Civil War

Innumerable obstacles having been surmounted, community life began at the Cerro de los Ángeles on October 31, 1926, Solemnity of Christ the King. An influx of new vocations soon filled the available openings in the novitiate, certainly thanks to the vibrant Carmelite spirit cultivated in the newly founded convent. The prioress was touched by an interior consolation, for finally the desires of the Heart of Jesus were being heeded: “How necessary it is to strive to be saints on this blessed Hill, where He desired with so much love to have His Carmelites abide, so as to be consoled by them and so that, with loving fidelity, they make Him forget the offences of His creatures!”8

Notwithstanding the hopes that these first years brought, dark clouds began to gather on the national political horizon in 1931, until the storm broke out in 1936. Bloody religious persecution was imminent, with great risk of a sacrilegious attack at the Cerro de los Ángeles.

St. Maravillas lost no time. In 1931, she had written to the Provost General of the Discalced Carmelites, requesting his permission, and that of the Holy Father, to carry out a desire of the entire community: to offer their lives in defence of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in the event that the monument were attacked. In this letter, one of the most beautiful of her epistolary, she says: “Will the Carmelites find themselves forced, by holy cloister, to see Him cast down from His throne without being able to fly to Him and defend Him, or at least to not leave Him alone among His enemies, without finding at His side hearts, poor though they be, as He well knows, but burning with love? Our father, this would be the cruellest martyrdom, even greater than the loss of life. If He must hear cries of hatred from His enemies, may He also hear our praises.”9

But God did not call them to martyrdom: He wanted their willingness to suffer without the loss of their lives, and He saved them from danger through means baffling to human eyes.

The mayor of the city of Getafe, where the Hill is located, was at the time a dreaded anarchist nicknamed the Russian. Although Republican ruthlessness had rendered him a brute, the Russian felt drawn to visit the Carmel and to become acquainted with St. Maravillas. He appeared often at the locutory to engage in lively conversation with her, unable to hide his sincere admiration. They spoke about his family, the upbringing of his children, the direction that society was taking and, naturally, of the Carmelite life. He was soon won over by the gentle manner of the Mother, who had a goodness he had never experienced in his interaction with his militia comrades.

When the war began, the Russian made a secret resolution to save the lives of those Carmelites, and at the climax of the persecution he sent a supply truck to the Hill of the Angels with strict orders to remove them from the site. St. Maravillas and her community obeyed and, not without facing grave risk during the journey, they arrived safe and sound at the doors of a convent of foreign nuns, where Spanish agents were prohibited from entering. In this way, they were spared the fury of the militiamen thanks to an order from their dreaded leader!

This is but one of many episodes that eventually convinced St. Maravillas that they were aided by an invincible protection. Indeed, the greater the danger, the more striking was the intervention of Providence.

At the end of the war, they returned to rebuild the monument and the demolished Carmel, fervently resuming the mission entrusted to them: “Since the Lord did not wish us to be martyrs, as we desired, and has brought us again to His side, let us work as true daughters of the Holy Mother [Teresa] to make Him reign in Spain and in the whole world.”10

An interior life marked by suffering and struggle

In the soul of every Saint there is a vast interior universe dedicated to intimacy with God, where they dwell in thoughts far superior to the concrete reality surrounding them. By following the trajectory of her mystical life, we are able to understand the true course of her life, in which exterior events represent but a small part.

To lift the veils of the soul of St. Maravillas is to awaken veneration for her grandeur of spirit and for her great capacity to confront suffering – something impossible to comprehend without the heroism of the virtue of faith. Whoever analyses the expression of her countenance perceives that her undeniable human qualities were not the only reason for the success of her works; the tremendous interior trials that accompanied these conquests were their main cause. “Her life, like all true lives, was forged in the trial of darkness.”11

The dark night of the senses, which those who allow themselves to be sanctified by God undergo, accompanied her for many decades of incessant struggles: “At first glance we cannot comprehend how an interior world so filled with suffering could coexist with an external activity filled with vitality. In fact, while everything in her soul suffered devastation, in the outside world she dedicated herself to building and founding convents; while she suffered an endless interior solitude, her daughters and those who knew her revered and loved her with a most sincere affection; while they honoured and cherished her as prioress, she had the inner conviction of being nothing. This type of contradiction between her interior and exterior world reflects the war to which she was submitted and proves in the Mother the fundamental Christian truth: in the Cross is life, from it flowed such great wealth from her poverty; from the experience of her limitation shone forth that unlimited light that so many observed; from her emptiness was born the superabundance of the Spirit that recreates all things.”12

Those who today pause to consider the vast work of St. Maravillas understand that physical and moral sufferings accepted with abnegated resignation were the price paid for the greatest cycle of Carmelite foundations after that accomplished by St. Teresa herself.

Founding of eleven new Carmels

Attracted by the extraordinary supernatural life that developed around St. Maravillas, many young women knocked at the doors of the convent requesting admission: “It seems incredible that, with the world in its present state, there are so many vocations to this way of life, for they really are so very numerous, and it is necessary to do whatever we can to help them.”13

The promoters of the Civil War surely found their efforts frustrated in face of this nun’s power of attraction, which not only rebuilt and repopulated the destroyed convent, but also erected eleven new ones, in addition to undertaking the reform of the one in which she herself had entered. Crowning all of her works for the Carmelite cause, she was yet able to achieve an magnum opus: the spiritual and material reform of the Convent of the Incarnation of Avila, where St. Teresa of Avila lived for twenty-seven years. These new Carmels were born in the finest Teresian style, bringing back to life, at the height of the twentieth century, the pages of the Foundations in the beautiful Castilian lands.

The enemy of our salvation could not bear such a blow and he set about to disturb daily life in the convents. Thus, it fell to St. Maravillas to confront the devil’s fury with vigorous exorcistic interventions, as is registered in her process of canonization: “She did not have special or outstanding charisms, but she had to confront terrible diabolical manifestations, including external ones.”14

Let yourself be led by the divine will

The constant dealing with souls in the fulfilment of her office as prioress, held from her younger years until her death at eighty-four years of age, provided St. Maravillas with a profound knowledge of human nature and, sad to say, of the many human obstacles set up against the interior stirrings of grace: “I believe that our nothingness and misery are of absolutely no importance to Our Lord; He has taken upon Himself the task of arranging, cleansing and changing; the important thing is that we love Him and make His divine will completely ours […], so that He alone governs our life, in great and small things, external and internal, and we concern ourselves only with fulfilling His will and, above all, in letting Him fulfil it in us.”15

Summarizing this invariable guidance given to her religious, she would repeat it to them with Spanish verve and great charm upon noting in one of them a voluntary opposition to God’s designs: “Si tú le dejas… – If you let Him act…”

She died on December 11, 1974, in the Carmel of La Aldehuela, near the Cerro de los Ángeles, one of the last she had founded. Her serene death, accompanied by the fragrance of precious nard that emanated from her body, highlighted the entrance into eternity of this perfect Discalced Carmelite, who left to her daughters and to posterity this message: “The truth is that we are happy! If the Lord were to ask us about one thing or other, of the moment of our death, of which illness we would wish to die from, of how we would want it to be, etc., we could only say to Him: ‘Lord, when Thou wishest, as Thou wishest, what Thou wishest…’ This is all we want and desire. Thus will take place the complete realization of our desires, which are nothing other than His will.”16 ◊

Notes